In this post, I will describe and prove a concept from physics/optics known as Snell’s Law. Then, just for fun, I will apply it to an interesting “quickest path” problems from pure mathematics that will probably never occur in any physical scenario.

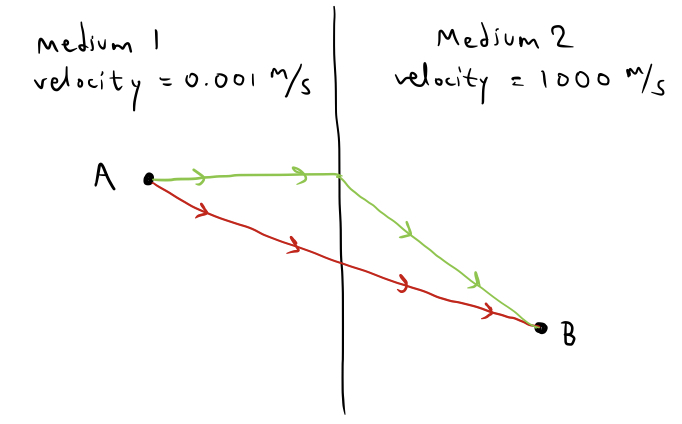

In physics, Fermat’s Principle is the assumption that when light travels from one point in space to another, it always takes the quickest path. In some scenarios, the quickest path between two points is the straight line connecting them, but this is not always the case. The maximum velocity at which light can travel varies based on the medium through which it travels, whether it be air, water, glass, or empty space. When a ray of light has to transfer from one medium to another to travel between two points, it turns out that the fastest path it often not a straight line. This is partially because a straight line path may cause the ray spend “too long” in a medium that slows down its velocity, whereas it could have gone faster by transferring first to a medium in which it can travel more quickly. Consider this simplified example:

Clearly, even though the red path is the path of shortest length, following the green path would be quicker. This is because the time spent in medium $2$ will be negligible compared to that spent in medium $1$ because of the much higher velocity in medium $2$, meaning that it would be quicker to get out of medium $1$ as quickly as possible, and then head towards point $B$. That’s not to say that the green path is optimal - that was just a conceptual thought experiment. Now let’s use math to calculate the actual optimal paths.

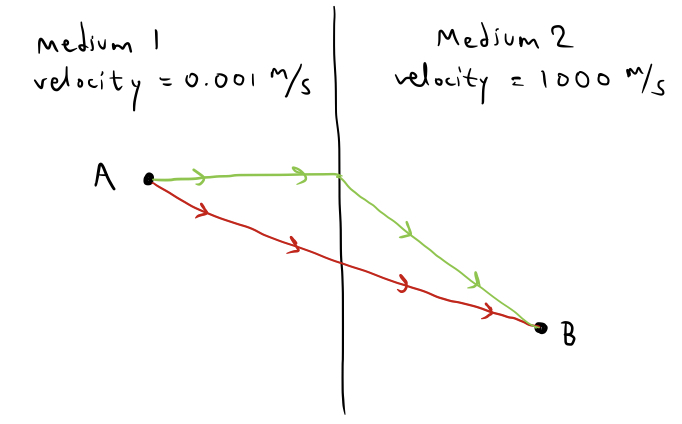

Consider an arbitrary scenario in which the two media correspond to velocities $v_1$ and $v_2$ and the start and end points of the path are respective distances $d_1$ and $d_2$ from the interface between the media, with a vertical distance $h$ between them. Further, we may assume that within each medium, the shortest path is a straight line, so the optimal path consists of two line segments. In the image below, I have characterized these line segments by the respective angles $\theta_1$ and $\theta_2$ that they make with the normal line:

We may easily calculate with a bit of trig that the vertical distances travelled in each medium are $d_1 \tan(\theta_1)$ and $d_2\tan(\theta_2)$ respectively, and the total distances travelled in each medium are $d_1\sec(\theta_1)$ and $d_2\sec(\theta_2)$ respectively. Thus, since the total vertical distance travelled is $h$ and we wish to minimize the total time spent, we can reduce the problem to the following: we need to minimize the quantity subject to the constraints and $\theta_1,\theta_2\in (0,\pi/2)$.

Because of the constraints, we have that $\theta_2$ is actually a function of $\theta_1$ (and vice versa). This means that we may differentiate the first expression with respect to $\theta_1$ and equate it to zero (in order to calculate the optimal $\theta_1$ and $\theta_2$ values), yielding the following: which is equivalent to Now, if we differentiate the equation representing the first constraint with respect to $\theta_1$ as well, and perform a few algebraic manipulations, we obtain the following equation: Combining this with the above equation yields the following: or This simple, pleasing result is known as Snell’s Law, and determines the quickest path between two points in different media with a linear interface between them.

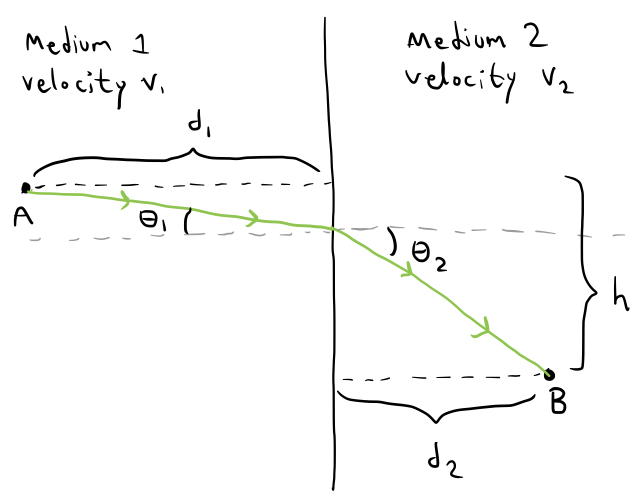

Now let’s use Snell’s Law to tackle a different and much more interesting problem. Suppose you are in a vehicle represented by a point on the two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate plane. You wish to travel from some point $A$ to another point $B$ as quickly as possible, and the maximum instantaneous velocity of your vehicle at any time is also equal to its y-coordinate. How can you find the optimal path?

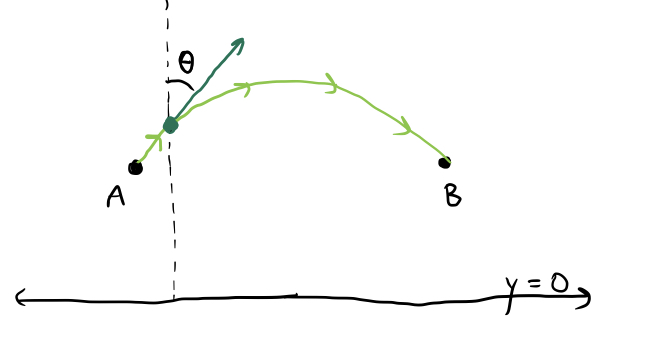

At first, this seems like a completely different problem, since there is no discrete differentiation between media in which the particle has different velocities. Rather, there is a continuum of velocities at which the particle may travel. Once again, before actually tackling the problem, let’s do a little thought experiment to assure ourselves that the quickest path will not be a straight line. Suppose, for example, that points $A$ and $B$ are at the same y-coordinate, but are very far away:

Then the green path marked above might easily be faster than the red one, because although it goes “out of the way” by unnecessarily moving upwards, it saves some time since the longer stretch of the path takes less time, being at a higher altitude and thus being traversed at a greater speed.

Now I will explain an actual numerical solution. If you want to try the problem, do so now, before reading on.

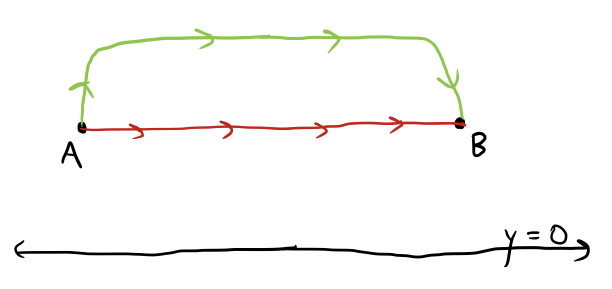

To simplify things, let’s suppose that point $A$ is the point $(0, h_0)$ and point $B$ is the point $(x_1,h_1)$. Even though there are no discrete medium-changes in this problem, we can still use Snell’s Law to help us - just think of each line $y=a$ as an infinitesimally thin medium. If the trajectory of our vehicle follows the quickest path, then we know by Snell’s Law that the angle $\theta$ that our trajectory makes with the vertical satisfies the following equation: where $\theta_0$ and $v_0$ are the initial angle and initial velocity. We can simplify this by saying that where $k$ is some constant. Let’s draw another picture:

If we represent the optimal path as the curve of a function $y=f(x)$, then we can see that at any value of $x$, the angle $\theta$ satisfies Notice now that $\sin(\theta)$ is actually determined by the slope of the curve. The slope of a line with angle $\theta$ from the vertical is equal to $\cot(\theta)$, meaning that the slope of the curve $y=f(x)$ at a particular x-value is equal to $\cot(\theta)$, or $y’=\cot(\theta)$. Since we may combine this with the above equation for $\sin(\theta)$, telling us that This is a pretty gross differential equation to solve, so I’ll omit the algebra and leave that up to any reader who is sufficiently interested to crunch the numbers. Solving the differential equation and using the initial values $y(0)=h_0$ and $y(x_1)=h_1$ to solve for the constant $k$ and the constant $C$ that appeared as a result of solving the differential equation results in the following solution:

Miraculously, this is the equation of a circle! So it turns out that the solution to our difficult and complicated problem is to simply travel along the circle passing through points $A$ and $B$ whose center lies on the x-axis, according to Snell’s Law. In fact, we can also calculate the amount of time the journey will take by calculating the integral

Solving this integral also requires a lot of messy algebra, but an exact answer can be found for its value as well:

And that concludes this brief blog post.