When computers transmit messages using either radio waves or fiber-optic cables, they begin by encoding the message (whether it be a text file, image, video, or audio file) as a sequence of ones and zeroes. However, a computer does not simply send the raw message along to the next router, switch, or host; rather, the binary data is compiled into a packet. Packets include not only the message to be transmitted, but also information needed to forward the packet along to its destination, as well as ensure its integrity. This might include the IP address of the sender, the IP address of the intended recipient, and a checksum used for detecting random bit errors in the packet, among other things. (If the packet is transmitted wirelessly, errors can be caused by interference of radio waves, and if transmitted electrically through a cable - believe it or not - cosmic rays from the sun can cause bursts of errors in the message.) In general, the portion of the packet not comprising the message is called the header.

The transmission of binary packets from one host to another might seem like a rather boring and abstract topic, but it actually gives rise to some very interesting logistical problems. In this blog post, I’ll discuss a couple of fun probabilistic optimization problems regarding packet fragmentation. Most of these problems can be solved using elementary calculus.

Let’s start by considering one mechanism that computer networks use to mitigate the uncertainty caused by random errors: ACK packets. When a host receives a packet from another host, it typically sends an ACK packet (“acknowledgement packet”) back to the sender in order to communicate that the message was received successfully. If the host receives a packet that has been corrupted by bit errors, it discards the packet without sending an ACK packet, and when the sender fails to receive an ACK packet after a certain duration, it assumes that its message has been lost and proceeds to re-send the message. However, since all packets are susceptible to bit errors, including ACK packets, there’s a chance that the message will be successfully received and the ACK packet will be lost, causing the sender to re-send unnecessarily.

Here’s a simple problem to consider. It’s not an optimization problem, but rather an exercise in calculating expected value:

Suppose that one host wants to send a packet with a size of $B$ bytes to another host. If it is received, the receiver will respond with an ACK packet. Any packet has a probability $p$ of being lost due to bit errors. On average, how many bytes will the sender have to transmit before being satisfied that its message has been received?

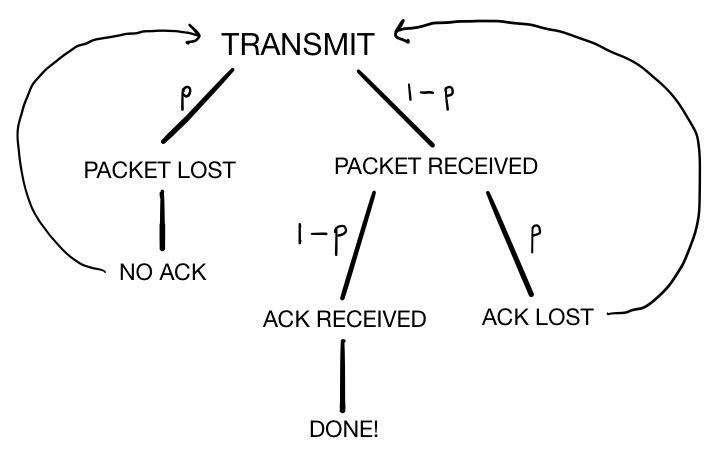

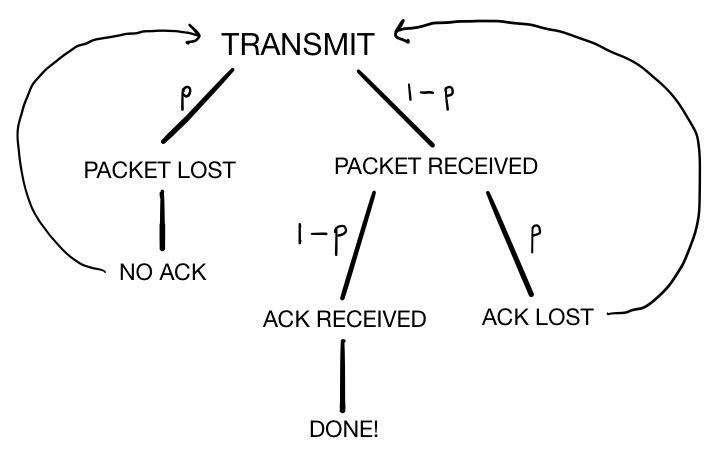

From the sender’s point of view, when it sends a packet, there are two possible outcomes: it might receive an uncorrupted ACK packet, in which case it knows that its message was received and can safely stop transmitting; or it might fail to receive an ACK packet because either its message or the ACK packet was corrupted, in which case it must re-transmit the packet. We can draw a tree to visualize these possible outcomes and their probabilities:

Therefore, if $\bar{B}$ is the average number of bytes needed to ensure that the message is transmitted, we have the following equation:

Solving for $\bar{B}$ yields the answer to our question:

For example, if our packet consists of $B=100$ bytes and there is a $p=0.01$ rate of packet corruption, then the average number of bytes actually transmitted by the sender would be approximately $102$ bytes.

This simple example assumed that all packets have the same rate of corruption $p$. However, in practice, this is not the case. In reality, larger packets are more susceptible to corruption, since they contain more bits and each bit has a certain chance of being affected by bit errors. In the next problem we tackle, we shall assume that each bit in a packet is equally likely to be affected by an error. This is not quite true, since bit errors actually tend to occur in bursts, affecting many subsequent bits at once. We’ll also assume that a single bit error will irretrievably corrupt any packet, which is also not completely realistic, since checksums sometimes allow for correction of bit errors. These two (admittedly unrealistic) assumptions will serve to simplify the problem.

As mentioned above, large packets are more susceptible to bit errors and corruption, so it can be advantageous to split large messages into multiple pieces and send each piece in a separate packet (if this strategy is used, the packet header might contain information about how the receiver should reassemble the message fragments). This way, if a bit error occurs, the sender won’t need to re-send the entire large message - only the affected packet will need to be sent again. However, this does not mean that we should split messages into as many separate packets as possible. Remember that each packet must have its own header, which serves as a kind of “fixed cost.” Sending many small packets might reduce the damage done by packet corruption, but it increases the number of extra bytes used to transmit headers.

For example, suppose you want to transmit a message consisting of $100$ bytes, and all packets must include a $10$ byte header. If you send this as a single enormous packet, the number of bytes wasted on headers is only $10/110\approx 9.1\%$ of the packet size. If you split it into two packets, you’ve somewhat insured your message against bit errors, but you’re now wasting about $10/60\approx 16.7\%$ of each packet on headers. If you split the message into $10$ separate packets, you’ve doubled the total number of bytes that you have to send, since $50\%$ of each packet consists of a header. Clearly there’s a tradeoff between insuring against packet-corruption and conserving packet-header bytes, which we can quantify in the following (simplified) optimization problem:

Suppose you want to transmit a message of $B$ bytes by splitting it up into packets, each of which contains $b$ bytes of message and $h$ bytes of header information. Each bit has probability $p$ of being affected by an error. You may also assume the following: - Any packet affected by an error is corrupted and discarded. In other words, no checksums are being used. - ACK packets are sufficiently small that they are almost never affected by bit errors, so for the sake of this problem, ACK packets cannot be lost.

How many message bytes should you include in each packet in order to minimize the expected number of bytes needed to transmit your message? (That is, what value of $b$ minimizes the expected number of bytes transmitted?)

The first step in the solution of this problem is finding a function to minimize. Again, let $\bar{B}$ represent the expected number of bytes needed to transmit our message, as a function of $b$ ($B$, $p$, and $h$ are all constants). Suppose that we try to send some packet consisting of $B_{\text{pkt}}$ bytes, which includes a header. The probability $p’$ that the packet is corrupted equals the probability that any one of its bits is corrupted, implying that

By using reasoning similar to that used to solve the earlier exercise, we have that the average number of bytes needed to send this packet must be equal to

Now let’s return to the original problem. If we split our $B$ -byte message into smaller messages of size $b$, we will need approximately $B/b$ packets to transmit the whole message, and each packet will consist of $b+h$ bytes. Thus, multiplying the expression above by $B/b$ and substituting $B_{\text{pkt}}\to b+h$ yields an expression for $\bar{B}$, the expected number of total bytes needed to transmit the message:

Now we’re ready to optimize! Let’s differentiate this expression with respect to $b$:

Suppose $b_m$ is the optimal value of $b$. Then evaluating this derivative at $b=b_m$ should yield zero, so that

We can simplify this equation considerably. Multiplying both sides by $-b_m(1-p)^{8(b_m+h)}$ produces the equation

This can easily be rearranged into a quadratic equation in $b_m$:

Solving this quadratic gives us the final answer:

Interestingly, the optimal message fragment size doesn’t depend on the size $B$ of the original message. Let’s use this formula to calculate a quick example before moving on. Suppose that the header size is $10$ bytes and the probability of a bit error is $0.001$ (which would be really high for a bit error rate). Then, regardless of the size $B$ of your message, the optimal message fragment size would be approximately $b_m\approx 31$ bytes.

Apart from insuring a message against bit errors, packet fragmentation can also allow a message to be transmitted more quickly. Let’s ignore the possibility of bit errors for a little while and look at a few examples illustrating why fragmenting can be beneficial even when there is no risk of corruption. First, consider a simple scenario in which host $A$ wishes to transmit a message to host $B$ directly across a direct link:

Suppose that the propagation delay across this link (the time it takes bits to travel across it) is $40\space\mu\text{s}$, and the bandwidth of $A$ (the rate at which $A$ processes and sends bits) is $1\space\text{byte}/\mu\text{s}$. If $A$ needs to transmit a $100\space\text{byte}$ message with a $10\space\text{byte}$ header, the amount of time required to send the whole $110\space\text{byte}$ packet is equal to

In this case, there’s clearly no reason to fragment the packet (assuming bit errors are negligible), since doing so would just increase the amount of bytes used for headers and decrease the overall transmission time. However, seldom can a single host transmit a message to another host through a direct link. Let’s consider a slightly more realistic scenario, in which $A$ must transmit its message to $B$ through an intermediary router $R$:

Assuming both links still have a propagation delay of $40\space\mu\text{s}$ and both $A$ and $R$ have a bandwidth of $1\space\text{byte}/\mu\text{s}$, the time that it takes to transmit our $110\space\text{byte}$ packet is now equal to

However, it happens that we can counterintuitively reduce this time by fragmenting our packet. Suppose we break our message into two $60\space\text{byte}$ packets $P_1$ and $P_2$. The time required to transmit both $P_1$ and $P_2$ equals

This gets a little bit tricky to conceptualize, but here’s a step-by-step description of where each of these numbers come from:

Can you see why this is quicker than sending the message as a single packet? In short, it’s because it takes advantage of parallel processing: while some portions of the message are being processed, others are in transit or being processed elsewhere, rather than all of the message being processed at the same time and in the same place. Packet fragmentation allows a smaller proportion of the network to be idle at any given time, leading to greater efficiency. In fact, in this example, if we further split our message into four $35\space\text{byte}$ packets, we can reduce the transmission time even more to $255\space\mu\text{s}$. However, if we split it into five $30\space\text{byte}$ packets, the transmission time goes back up to $260\space\mu\text{s}$ because the efficiency gain due to parallel processing is finally overtaken by the inefficiency of spending too many bytes on packet headers.

We can easily formulate this tradeoff this as an optimization problem:

Suppose that host $H_1$ needs to transmit a message to host $H_2$ through the intermediate router $R$: The size of the message is $B$ bytes, and the size of a packet header is $h$ bytes. The propagation delay across both links equals $d$ microseconds, and both $H_1$ and $R$ have a bandwidth of $w$ bytes per microsecond. Approximately how many packets should the message be fragmented into, in order to minimize transmission time?

Suppose we break the message up into $n$ fragments, so that the size of each packet is approximately $h+B/n$. By extending the same line of reasoning as we used in the previous example problem to the generalized problem with $n$ packets, we can calculate the total delay $T$ in terms of known quantities:

To clarify this formula: the first term calculates the the time $H_1$ spends processing all $n$ packets, the second term represents the propagation delay of the final packet as it travels $H_1\to R$, the third term calculates the processing time of the final packet at $R$, and the fourth and final term is the propagation delay of the final packet across the link $R\to H_2$. Simplifying this expression yields the equation

Now, to find the value of $n$ which minimizes $T$, we should first differentiate this expression with respect to $n$ (treating it momentarily as a continuous variable):

This expression equals zero when $n=\sqrt{B/h}$, which is a rather elegant approximate answer to our original question! It is, however, merely approximate, since we made the mistaken assumtion that $n$ could be treated like a continuous variable that can be differentiated. We can also obtain an exact integer solution for $n$, although it will be a bit less pretty. Instead of considering the derivative of $T$, consider the finite difference of $T$ with respect to $n$:

The smallest value of $n$ for which this quantity is positive equals the optimal value of $n$ (or the value of $n$ that minimizes $T$). That is, we wish to find the smallest integer value of $n$ for which

or, by solving this quadratic,

Since $n$ must be an integer, we can obtain our answer by taking the ceiling of this expression:

So we’ve solved the problem. Interestingly, this problem has a natural generalization - what would be the optimal value of $n$ if, instead of just one intermediate router between hosts $H_1$ and $H_2$, there were $N$ different routers?

I’ve calculated that the “pretty” approximate solution is given by $n_m\approx \sqrt{BN/h}$. A derivation of this formula, as well as calculation of an exact integer solution, will be left to the reader, since both are very similar to the solution of the problem above.

One might also generalize all of the optimization problems we’ve considered in this post by creating one monstrous optimization problem that takes into account bit-errors and packet corruption, ACK packets, and parallel processing and intermediate routers. However, I haven’t yet worked this out myself.