Recently, Springer released a bunch of free textbooks, and I’ve been reading through one about astrophysics just for the hell of it. One of the first topics that the books covers is how the Earth’s rotation around the Sun produces day-night cycles and the seasons. As I was reading, it struck me that “day” and “night” on Earth could look completely different if a few parameters of Earth’s orbit - such as its rotation speed or axial tilt - were changed. In this post, I’ll begin by breifly explaining how Earth’s rotation around the Sun and about its axis produce the days and nights that we currently observe, and then continue to explore how they would change if we lived on a planet with a different trajectory.

EDIT (08/30/2020): As an assignment for my CS 152L Introduction to Java course at UNM, I designed a visual simulation of how the sun would look in the sky from a planet with different orbit parameters. Check it out!

Throughout this blog post, I’ve made a few simplifying assumptions to make the math easier:

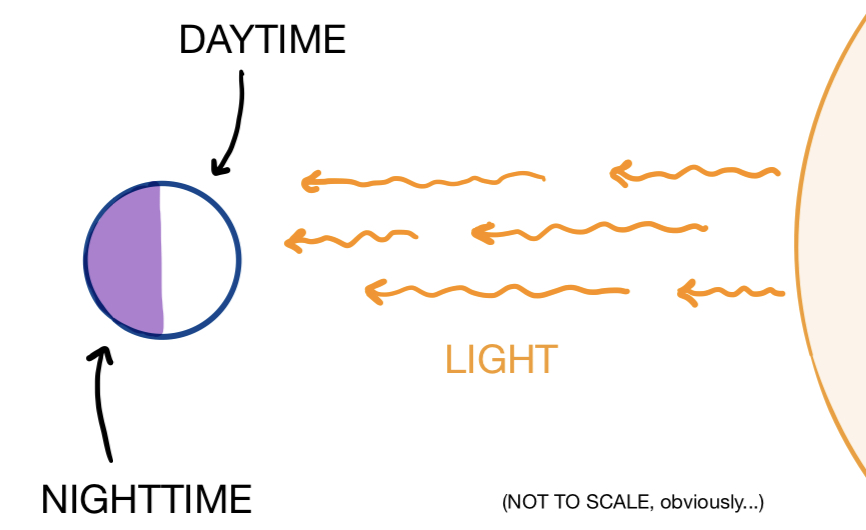

As you probably know, the “day” and “night” that we observe on Earth are a result of Earth’s rotation about its axis. You observe nighttime when you’re on the hemisphere facing away from the sun, and daytime when you’re on the hemisphere facing towards the sun. The cycle of facing-away-facing-towards repeats itself every $24$ hours, which is the length of a solar day.

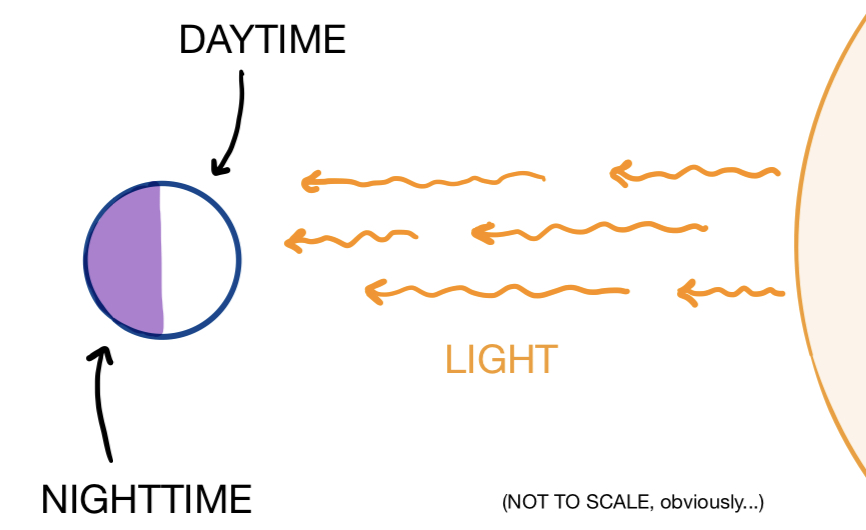

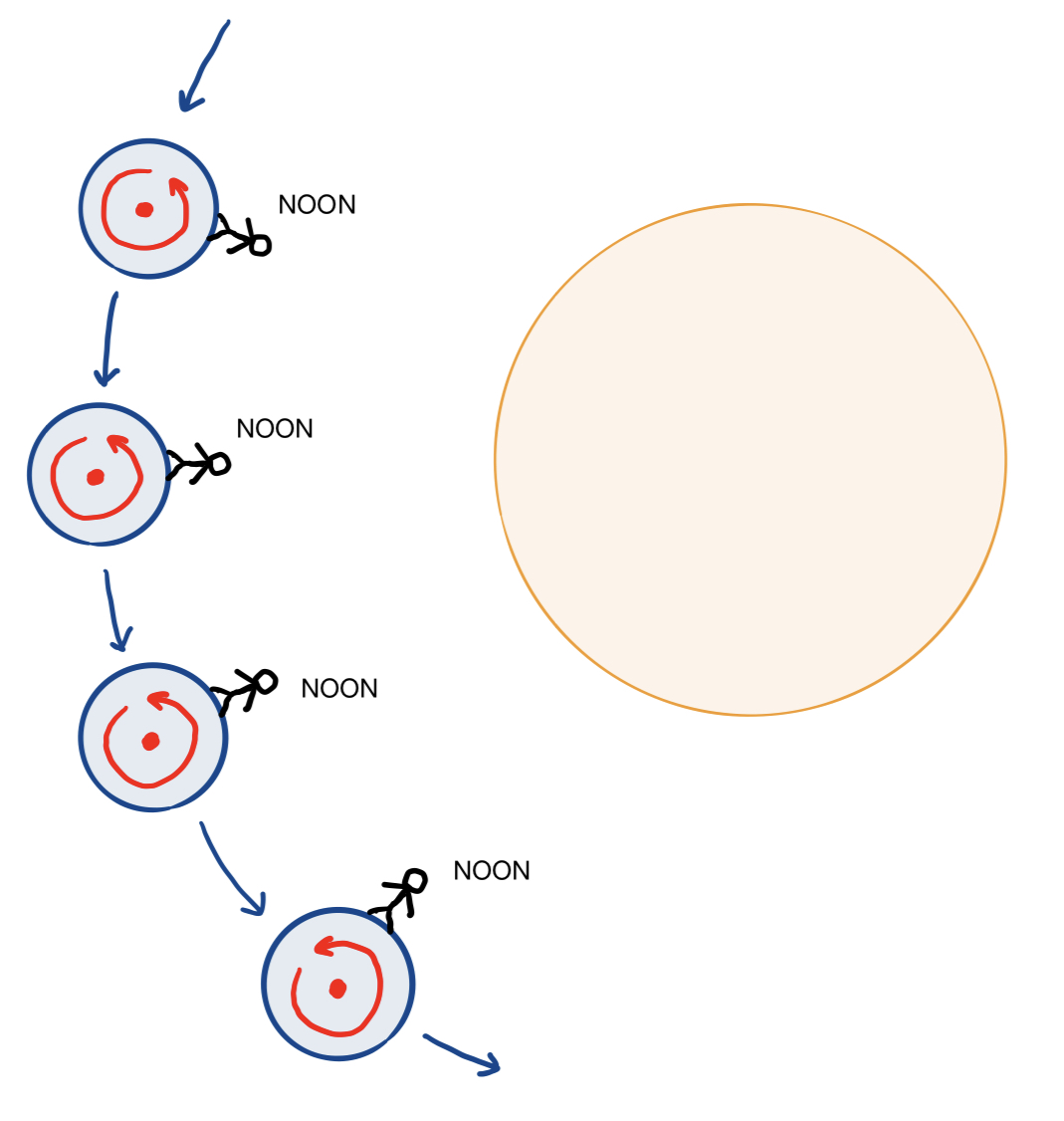

However, you may not know $24$ hours is not how long it takes for the Earth to rotate once about its axis. It actually only takes about $23$ hours and $56$ minutes for Earth to complete a full axial rotation. Why is this the case? By the time Earth has made a full rotation about its axis, it has also moved slightly farther along its orbit around the sun. This means that a little extra rotation is needed to bring it back to the same position relative to the sun. The figure below shows how, between the noons of two consecutive days, the Earth completes more than one axial rotation, slightly surpassing the original axial orientation (marked in pink):

The time it takes for Earth to rotate once about its axis is called a sidereal day. Whereas the solar day measures the time elapsed between two consecutive times that the sun reaches its highest point in the sky, the sidereal day measures the time elapsed between two consecutive times that any other star (about which we are not rotating) reaches its highest point in the sky. For this reason, sunrise and sunset times are offset from the rising and falling of stars, which is why you can see different stars in the sky at night depending on the time of year.

Knowing that a solar day is $24$ hours long, a solar year is about $365.25$ solar days long, and the Earth’s axial rotation has the same orientation (i.e. clockwise or counter-clockwise) as its orbit about the Sun, it’s pretty straightforward to calculate that the length of a sidereal day is about $23$ hours and $56$ minutes. Pick some other star in the sky as a reference point, like the North Star. Over the course of a year, you see the Sun rise and fall about $365.25$ times on average. However, if you could see the North Star during the daytime, you would see it rise and fall about $366.25$ times each year - terrestrial observers see one less sunrise and sunset per year because we spin around the sun as well as around our axis. Thus, a sidereal year is one day longer than a solar year! From this knowledge, we can easily calculate the length of a sidereal day: it is approximately $365.25/366.25$ the length of a solar day, or and $23.934$ hours is approximately $23$ hours and $56$ minutes!

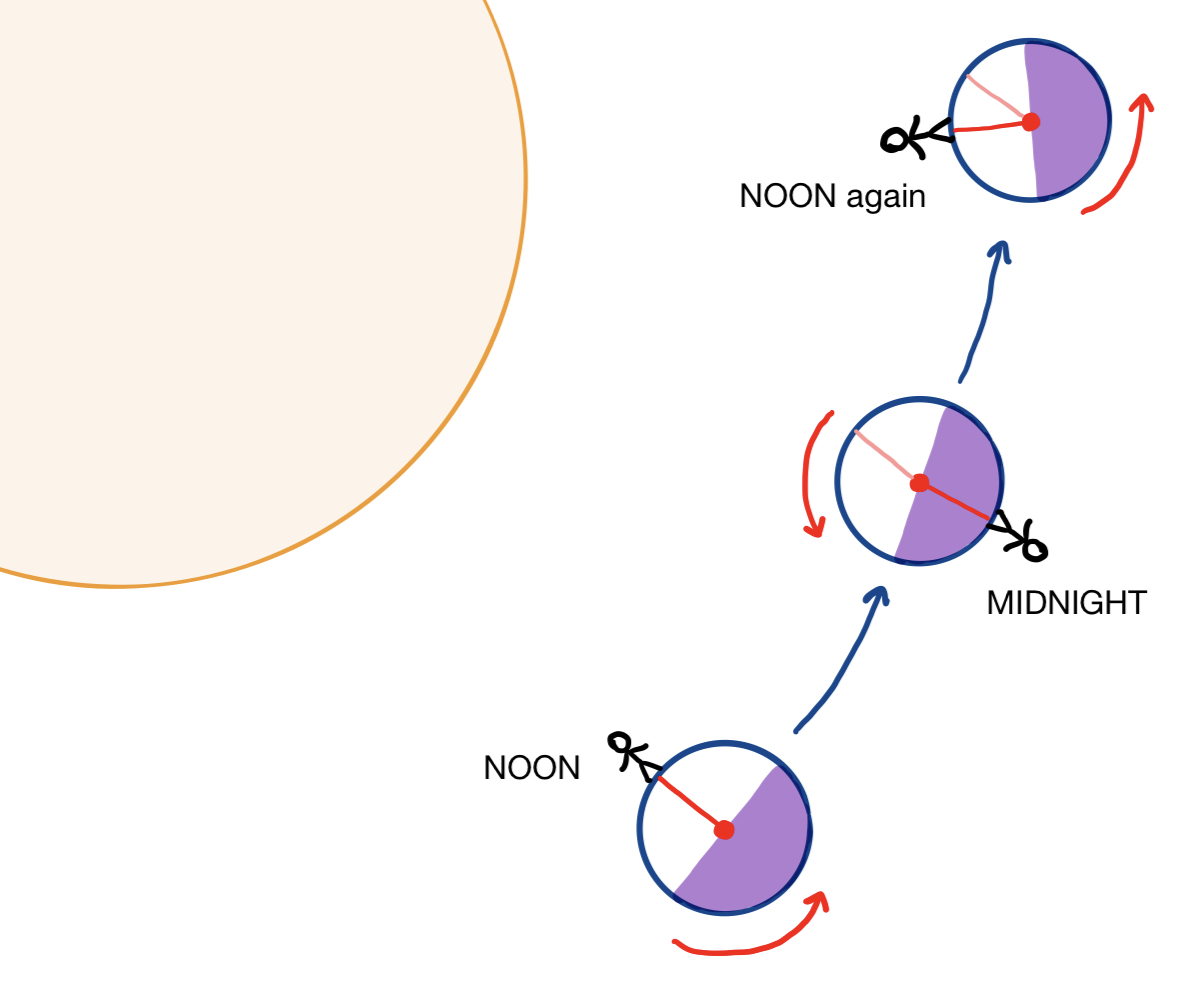

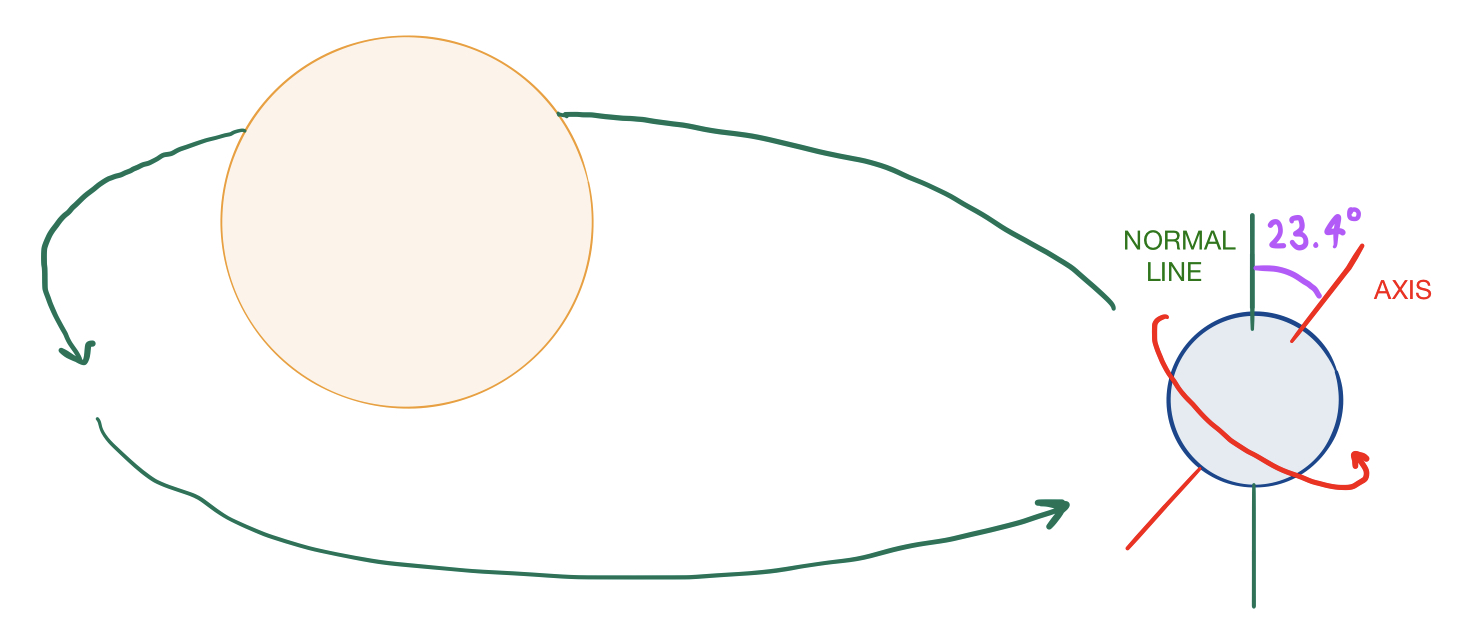

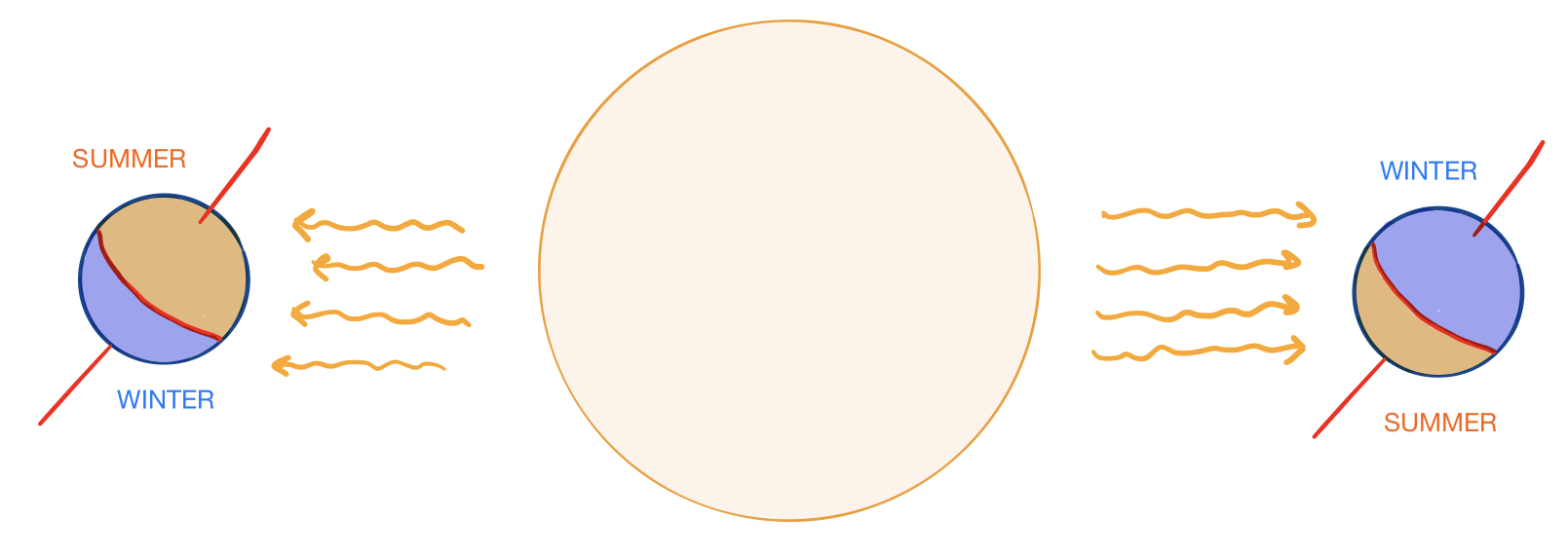

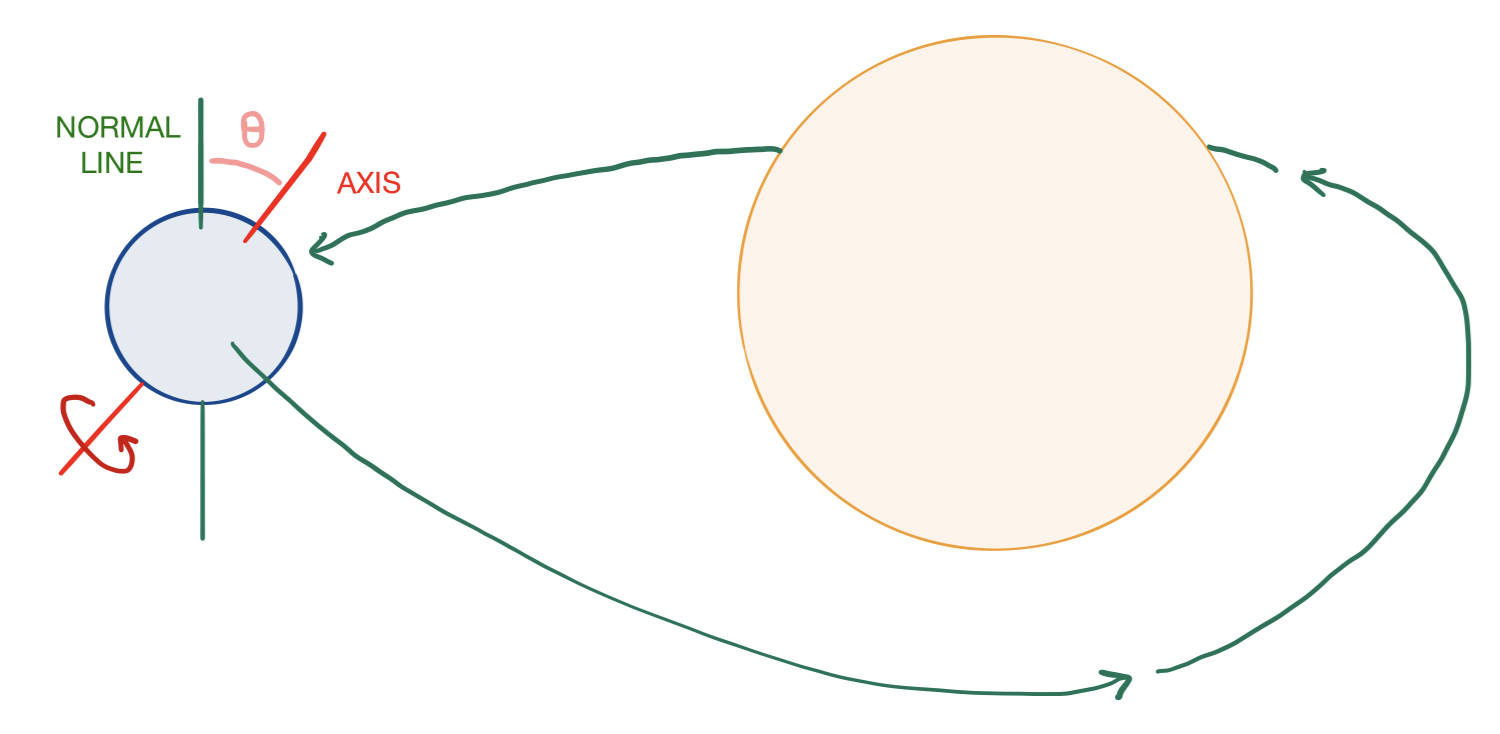

Now, how does Earth’s orbit produce the seasons? Earth’s axis is actually slightly tilted; that is, the axis about which the Earth rotates is not perpendicular to the plane in which the Earth orbits the sun. To be more exact, the angular deviation of Earth’s axis from the normal line to the plane in which it orbits the sun is approximately $23.4^{\circ}$.

This means that, at different points in Earth’s orbit, one hemisphere may be tilted towards the sun while the other is tilted away from the sun. In the hemisphere tilted towards the sun, the sun remains visible for a greater duration each day, and the sun’s light strikes the Earth more directly, making it summer. In the hemisphere tilted away from the sun, the sun is visible for a shorter duration each day, and sunlight strikes the surface at an angle, making it colder and therefore wintertime in this hemisphere.

Later on in the post, we’ll calculate approximately how much shorter/longer the days are in the winter and summer.

First, let’s consider how changing the direction and speed of a planet’s axial rotation would affect how we would perceive things from its surface. Consider the following puzzle:

Suppose a sphericalplanet is in a circular orbit about its sun, so that the length of a day is $10$ hours and the length of a year is $1000$ hours. Can you determine the angular velocity $\omega_{A}$ of the planet’s rotation about its axis and the angular velocity $\omega_O$ of its rotation about the sun?

Let’s give it a try. We can use the following diagram as a guide:

Obviously, we have that $\omega_O = 0.36^\circ/\text{h}$, since the planet orbits $360^\circ$ about the sun in $1000$ hours. However, calculating $\omega_A$ is a bit trickier. From this diagram, we can see that, as was true for Earth, the planet makes slightly more than a full $360^\circ$ rotation each day. By the same reasoning as before, because it circles the sun once over the course of a year, the number of axial rotations completed in a year is $1$ greater than the number of days in a year. In this case, there are $100$ days in a year, so the planet rotates $101$ times about its axis every $1000$ hours. This means that

So we’re done, right?

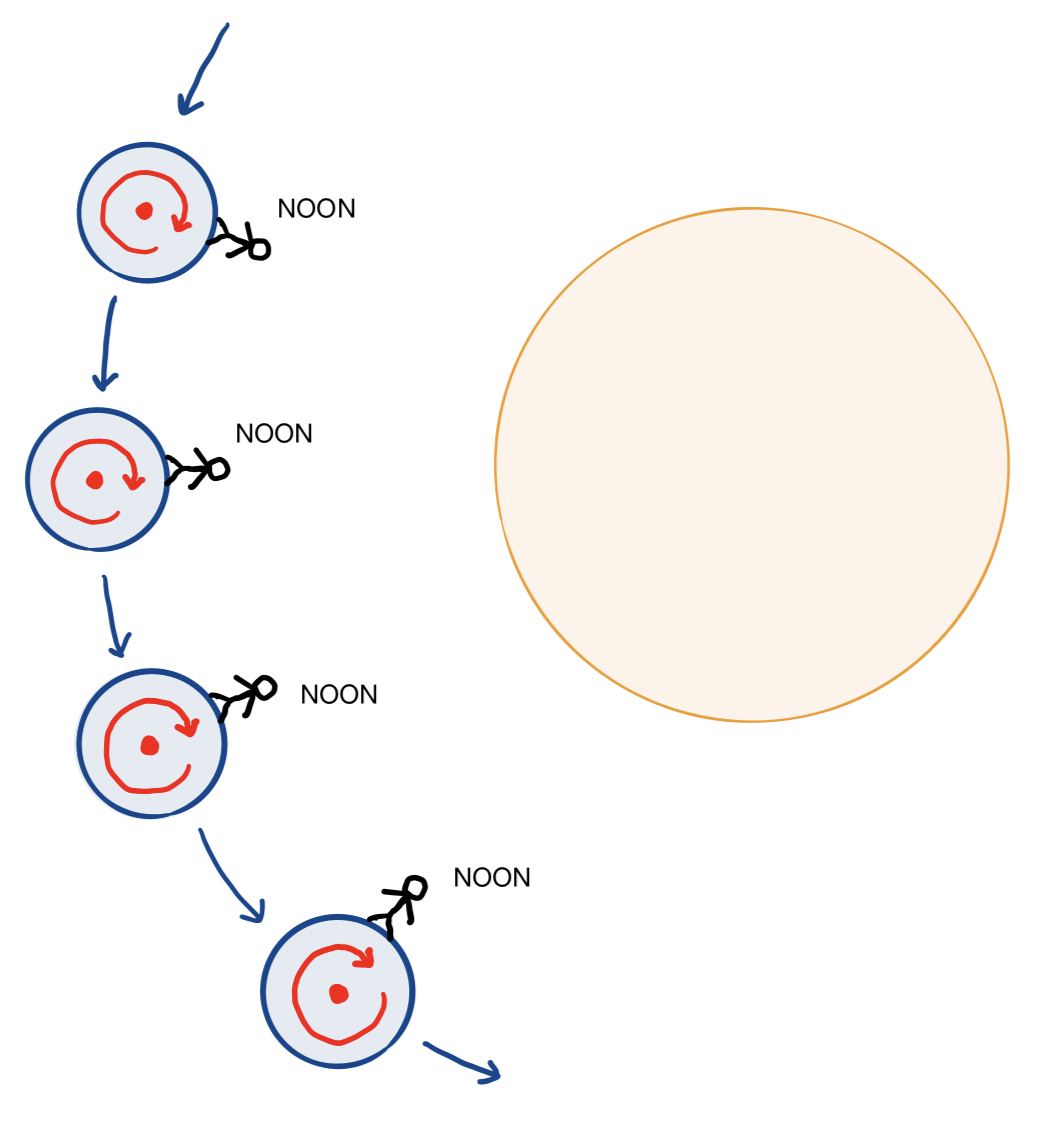

No! It turns out that there’s actually another possible answer. In the diagram that we used above, we made an implicit, unstated assumption that the planet’s rotation about its axis and its orbital movement had the same orientation, as is the case with Earth (i.e. either they both spin clockwise, or both counterclockwise). But what if the planet’s axial rotation is in the opposite orientation of its orbital rotation?

Then, instead of completing more than a full axial rotation each solar day, the planet would complete a little less than a full axial rotation. This means that there would be one fewer axial rotations in a year than the number of solar days in the year, or $99$ axial rotations every $1000$ hours. In this case, the axial angular velocity would be equal to

As a convention, we might instead write $\omega_A = -35.64^\circ/\text{h}$, using the negative sign to represent the fact that axial rotation is in the opposite orientation of orbital rotation.

So it turns out that knowing the length of a solar year and the length of a solar day on a planet does not uniquely determine its axial angular velocity! If you were living on this planet, how could you figure out whether your planet was spinning in the same orientation or the opposite orientation as its orbit? One possible way would be to keep track of sidereal time by observe the distant stars: if the axial and orbital rotations have the same orientation, the sidereal day is slightly shorter than the solar day, but if they have the opposite orientation, the sidereal day is longer than the solar day.

That was an interesting illustrative example, but it’s not very different from Earth - from the perspective of an observer on its surface, the structure of a solar day and a solar year would be very much like those of Earth. The solar day is a few hours long, and the solar year is tens or hundreds of solar days long. However, some special values of $\omega_O$ and $\omega_A$ can give rise to some more interesting and strange planetary conditions.

Of course, the most obvious example would be to consider extremely large values of $\omega_O$ and $\omega_A$, which would cause extremely short years or extremely short days. However, physics actually imposes a limit upon how long/short days and years can be for a planet of a particular size. A planet at a given distance from its sun must maintain a specific velocity in order to sustain a circular orbit about its sun, and it cannot spin too fast about its axis, because doing so would cause centripetal force to rip the planet apart. Let’s make these points more explicit by doing some calculations.

According to Newtonian physics, a planet of mass $M_P$ orbiting a star of mass $M_S$ at a distance $D$ is attracted towards the star with the following gravitational force:

where $G\approx 6.674\cdot 10^{-11} \space \text{m}^3/\text{kg}\cdot\text{s}^2$. Furthermore, the centripetal force needed to keep an object with mass $m$ in uniform circular motion with velocity $v$ and radius $r$ is equal to

In a circular planetary orbit, the centripetal force is supplied by gravity towards the star at the center of the orbit. This means that $F_g = F_c$, and

Note that $v = 2\pi D\omega_O$, so that

Solving for $\omega_O$, the orbital angular velocity, we have that

This means that a planet revolving around a star with a given mass at a given distance in a stable circular orbit must have orbital angular velocity determined by the above formula. The smaller the size of the star and the greater the distance from the star, the longer the length of a solar year must be. This formula imposes some clear restrictions upon the length of a solar year.

The possible values of $\omega_A$ are not as tightly restricted as the possible values of $\omega_O$, but we can nevertheless calculate an upper bound on $\omega_A$, putting a limit on how short days can possibly be. Just as a planet would be flung out of its orbit if it rotated its star too quickly, the planet would disintegrate if its axial rotation was too fast, since the gravitational force holding the planet together would not be enough to supply the centripetal force needed to sustain its rotation. For a particle of mass $m$ upon a planet’s surface, the centripetal force required to keep it from flying off into space is given by

where $R_P$ is the planet’s radius. The gravitational force holding the particle in place is equal to

To keep the particle on the planet’s surface, we need $F_g$ to equal or exceed $F_c$, or $F_g\ge F_c$. Thus,

which implies that

This imposes a bound on the maximum possible angular velocity of a planet’s axial rotation. For example, for a planet the size of Earth with the same radius, we have that

which means that, for a planet in the same conditions as Earth, a sidereal say could be as short as $1/0.712 \approx 1.404$ hours!

However, super-fast rotation is hardly the most interesting change that $\omega_O$ and $\omega_A$ could make to planetary surface conditions. Consider the scenario in which $\omega_O = \omega_A$. In this case, a “solar day” would not even exist, since the sun would only ever shine on one half of the planet! About Half of the planet would always be pointing towards the sun, and the other half would always be pointing away (this “dark side” of the planet would probably be perpetually frozen solid). However, the sun might not remain stationary in the sky from the perspective of a terrestrial observer: if the planet’s axis is tilted, the position of the sun in the sky would vary over the course of the year, but it would only “rise” or “set” in locations close to the poles.

Similarly, if $\omega_O\approx \omega_A$ instead of $\omega_O =\omega_A$, the planet would have days, but they would be extremely long. As in the case of $\omega_O\approx\omega_A$, the most noticeable movements of the sun in the sky would be those that result from the planet’s axial tilt and orbital rotation rather than its axial rotation. “Sunrises” and “sunsets” would be annual events rather than daily ones, and they would happen more frequently in locations near the poles. Given how the Earth’s regular day-night and seasonal cycles affect the circadian rhythm of animals and photoperiodism of plants on its surface, it’s interesting to imagine how an orbit in which $\omega_O\approx\omega_A$, with extremely long periods of daylight and nighttime and only occasional sunrises and sunsets, would affect the behavior of organisms on the planet’s surface.

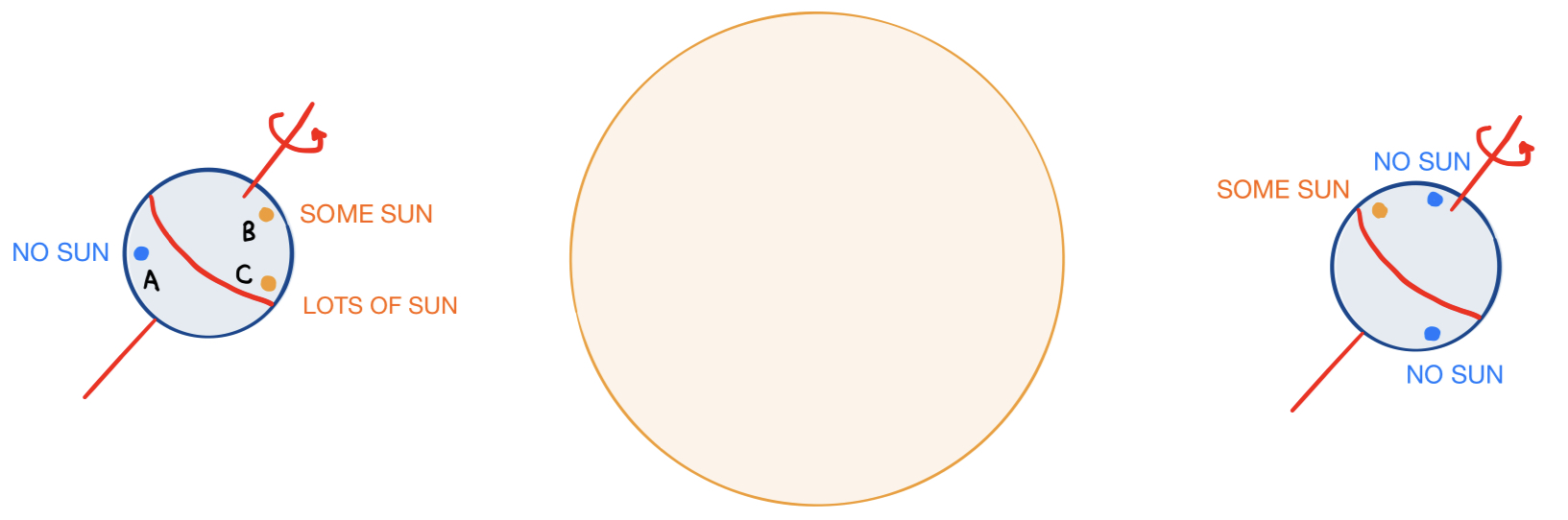

Now let’s figure out how the magnitude of a planet’s axial tilt would affect seasonal variations in daylight on its surface. Suppose (once again) that we have a planet in circular orbit about its sun, whose axis has an angular deviation of $\theta$ from the normal to the plane in which its orbit lies, as shown in this diagram:

Of course, there are some interesting extreme cases that we can easily evaluate qualitatively. For example, when $\theta =0$, there are no seasons whatsoever, and the amount of daylight in a solar day does not vary over the course of the year for any particular location. The other extreme case, in which $\theta = \pi/2$, would cause summers to have continuous sunlight, winters to have continuous darkness, and fall/spring to have normal days and nights that lengthen/shorten as summer/winter grow closer. However, I’d like to calculate a more specific mathematical answer to the following question:

Consider a planet in circular orbit with an axial tilt $\theta$ and a solar year that is much longer than its solar day (as is the case with Earth). At a point with given latitude $\phi$ on the planet’s surface, what is the approximate length of the longest solar day of the year (i.e. the day with the most sunlight), and what about the shortest solar day of the year?

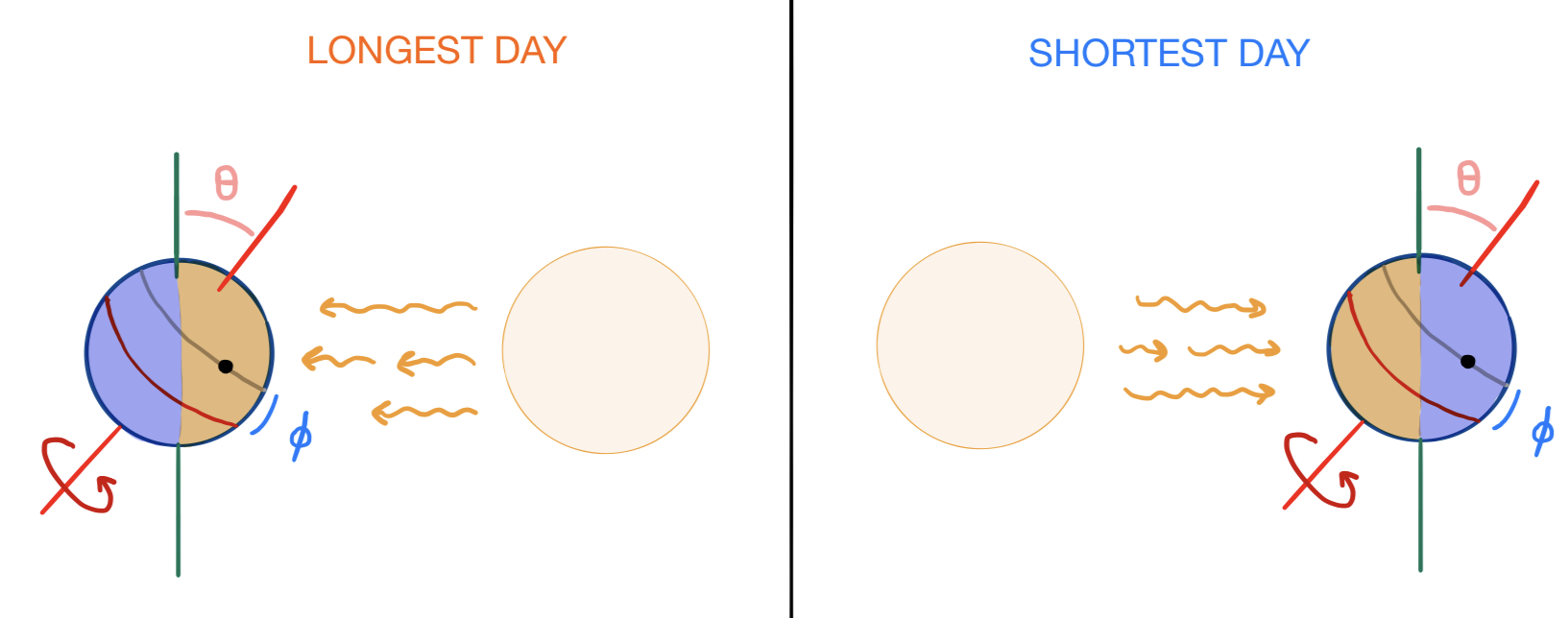

The simplifying assumption that the solar year is much longer than the solar day allows us to pretend that the planet stays in approximately the same location in its orbit in the time that it takes to make a full rotation from one noon to the next. Clearly, the longest day occurs when the hemisphere in which the point resides is tilted directly towards from the sun, and the shortest day when it is tilted directly away from the sun.

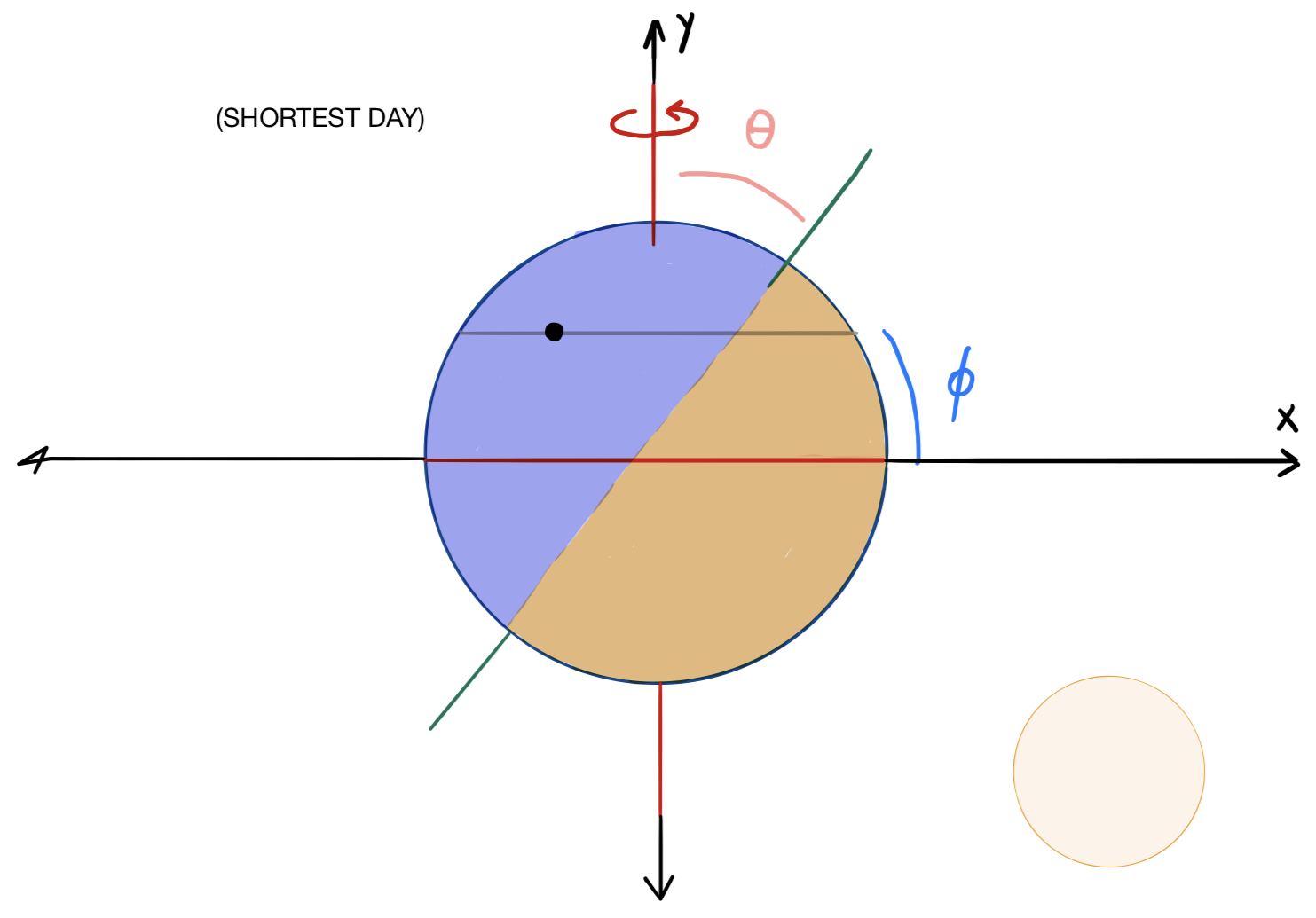

Further, since the point on the surface undergoes uniform circular motion relative to the planet’s axis, the proportion of the day during which the sun is visible in the sky is equal to the proportion of the circular path swept out by the point (shown in gray) that lies in the hemisphere facing the sun (highlighted in orange). To facilitate this calculation, let’s tilt our view of the planet from the side so that the axis appears vertical and the normal line tilted, and superimpose a coordinate grid upon this arrangement:

From this diagram, we can see that if $\pi/2 - \phi$ were greater than $\theta$, then the entire gray path traced out by the point would lie in the unlit (blue) hemisphere, in which case the proportion of daylight on the shortest day of the year would equal $0$. But this is an edge case, so let’s continue with our calculation.

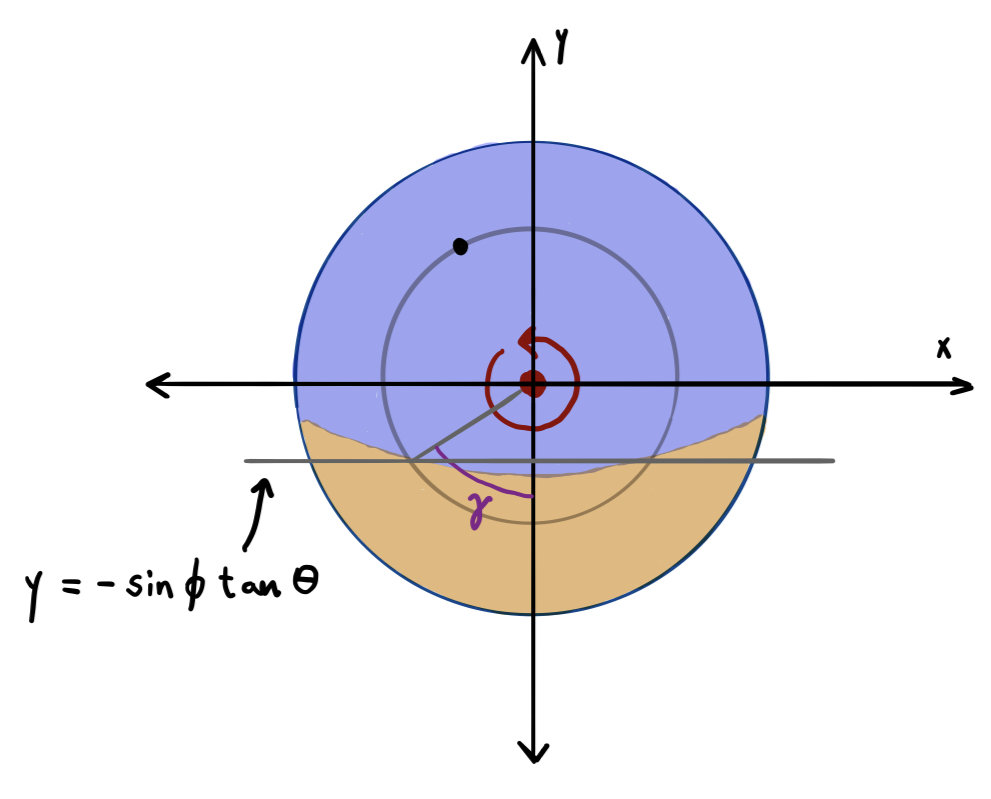

If we take the outline of this planet to be the unit circle in the Cartesian coordinate plane, then the normal line is given by the equation $y= x\cot\theta$ and the circular path traced out by the point, which looks like a straight line from this perspective, lies on the line $y=\sin\phi$. The intersection of these lines is where the point crosses over from darkness to light during its rotation, which occurs when $x\cot\theta =\sin\phi$, or $x=\sin\phi\tan\theta$. Now let’s look at this planet from the top, as if we were standing on top of its axis:

Again, let the outline of the planet be the unit circle. The gray circular path traced out by our point is now a circle with radius $\cos\phi$, also centered at the origin. With $\gamma$ defined as shown in the diagram above, we have that $2\gamma$ is the total number of radians that the point spends in the sunlight, and $2\gamma/2\pi = \gamma/\pi$ is the proportion of daylight on the shortest day of the year. Solving for $\gamma$, we have that

or

Which means that, if $d$ is the length of a day, then the length of time that the sun is shining on the shortest day is equal to

Let’s test out this formula. In Key West, the amount of daylight on the Winter Solstice is about $10$ hours and $36$ minutes. The latitude of Key West is about $24^\circ$, and

which is about $10$ hours and $30$ minutes, as expected! Of course, this formula won’t be exact, since the Earth is slightly oblate, but it’s pretty close!

Note that this formula is undefined when $\theta + \phi \gt \pi/2$ because of the limited domain of the arccosine function. This corresponds to the scenario in which the gray circle lies entirely within the unlit hemisphere, meaning that the shortest day receives $0$ hours of sunlight.

We might also like to know about the length of the longest day, but this question is trivial once we know the length of the shortest day: it’s simply the “opposite” of the length of the shortest day. That is, it’s equal to the length of a day minus the length of the shortest day. If you try working it out yourself the same way we did this problem, you’ll soon see why they’re equivalent problems.

And that concludes this blog post! There are lots of other interesting questions we might ask about different planetary configurations, but I’ve already covered enough in this post. So here’s a list of possible physics and geometry questions for you to consider, if you’re interested: