In my last post I introduced the parallel between propositions and types, and how this is used to do formal algebraic manipulations and proofs in Agda using the equality type. We demonstrated how algebraic identities can be broken down into sequences of basic steps and then "strung together", resulting in a nontrivial equality. We also discussed how equalities can be thought of as paths, so that applying the symmetricity of equality is like traveling a path in the opposite direction, and applying transitivity is like chaining two paths together at a common endpoint.

In this post, I'd like to focus in on associativity, a property belonging to many familiar binary operations on $\mathbb N$ such as $+$ and $\times$. On an arbitrary set $A$ (not necessarily $\mathbb N$), a binary operation $\star:A\times A\to A$ is called associative if it satisfies the property for all $x,y,z\in A$. When we do pen-and-paper algebra with $+$ and $\times$ in natural arithmetic, knowing that these operations are associative, we often neglect to write parentheses at all when we add or multiply three or more numbers. However, if you were to truly justify every step of your algebra and tabulate how many times each arithmetic property (commutativity, associativity, additive identity, etc) is used, you might notice that the number of association steps being glossed over is surprisingly large. For instance, suppose you wished to prove the simple equality using only commutativity and associativity, where the additions are implicitly left-associated. You'd think that in proving that the sum of a sequence of four number can be reversed without changing the value, the most frequently used law would be commutativity, but let's look at the proof:

Steps $1-3$ use commutativity, and steps $4-6$ use associativity. Associativity is used just as many times! To change a sum of four numbers from being right-associated to being left-associated, we need three extra steps, doubling the length of the proof. When we increase the number of terms to $5$, the number of associativity applications actually exceeds the number of commutativity applications - steps $7-10$ below apply commutativity, whereas steps $10-16$ apply associativity:

In fact, if we were to generalize this algorithm to re-associating a sum of $n$ terms, the number of commutativity applications required would be $\mathcal O(n)$, whereas the number of associativity applications required would be $\mathcal O(n^2)$. Luckily, this is not a problem in pen-and-paper arithmetic, because we are able to mentally abstract away this whole process and realize that $(((d+c)+b)+a)$ can be re-associated to form $(d+(c+(b+a)))$, even if we don't write out all of the steps explicitly. (Although, some mathematical hardliners might consider it non-rigorous or sloppy to skip even these "obvious" steps.)

However, when we do algebra in Agda, we must include all steps explicitly. Since the number of steps required to completely re-associate a sequence of $n$ additions from left-associated to right-associated grows quadratically as $\mathcal O(n^2)$, if we are doing algebra with many terms, the number of associations needed may completely swamp the number of other identities needed, making for a proof that is very verbose and tedious to write. That's why, in this post, we will set out to write a function in Agda that abstracts away this process, allowing us to perform arbitrarily many re-associations in a single step.

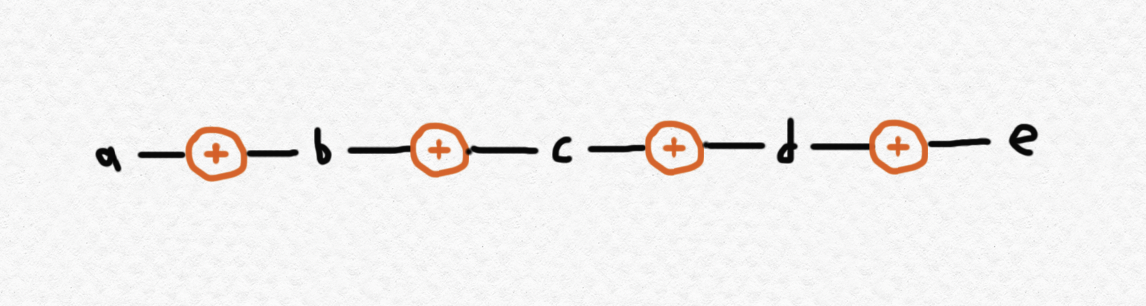

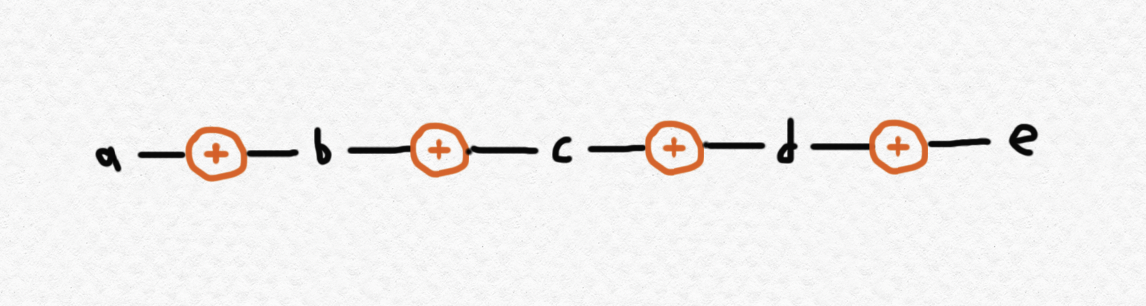

When dealing with an associative operation like $+$ (addition) or $\circ$ (function composition), we often write repeated applications without parentheses like this: so that we might like to think of the numbers $a,b,c,d,e$ as being "combined" in a "linear sequence" or a "chain", like this:

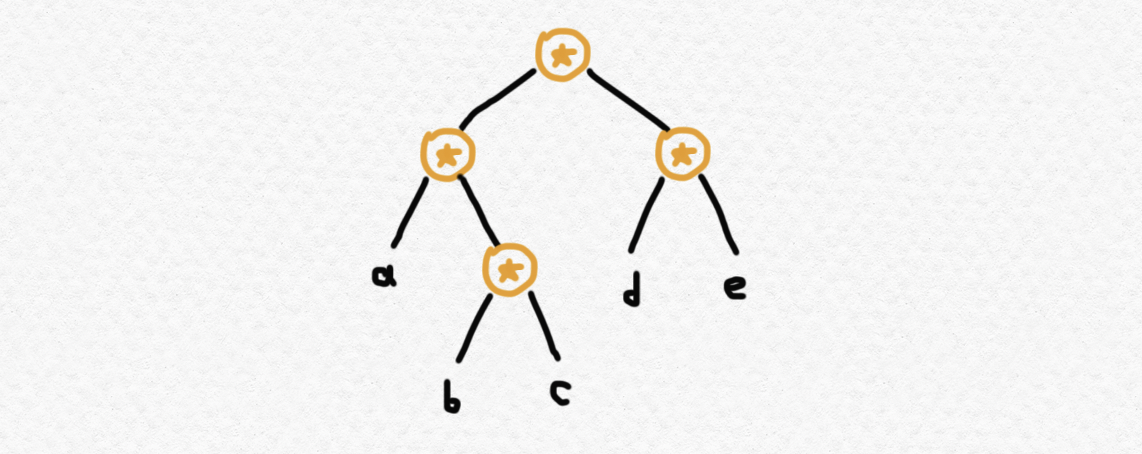

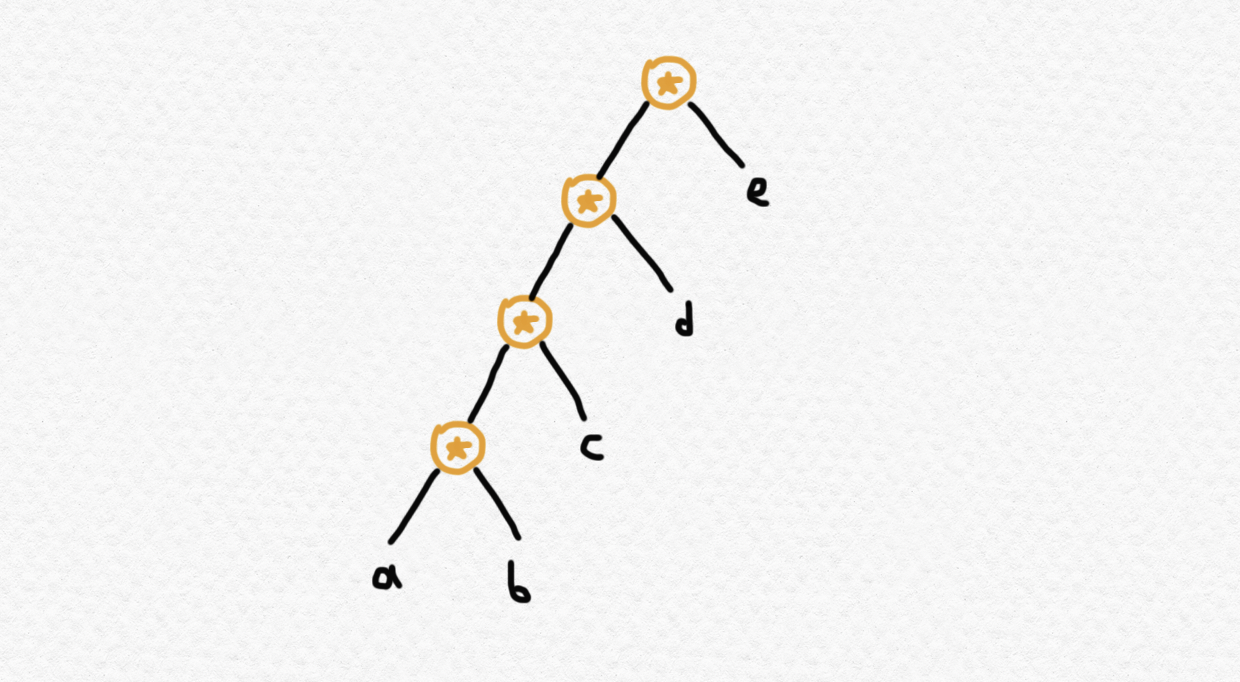

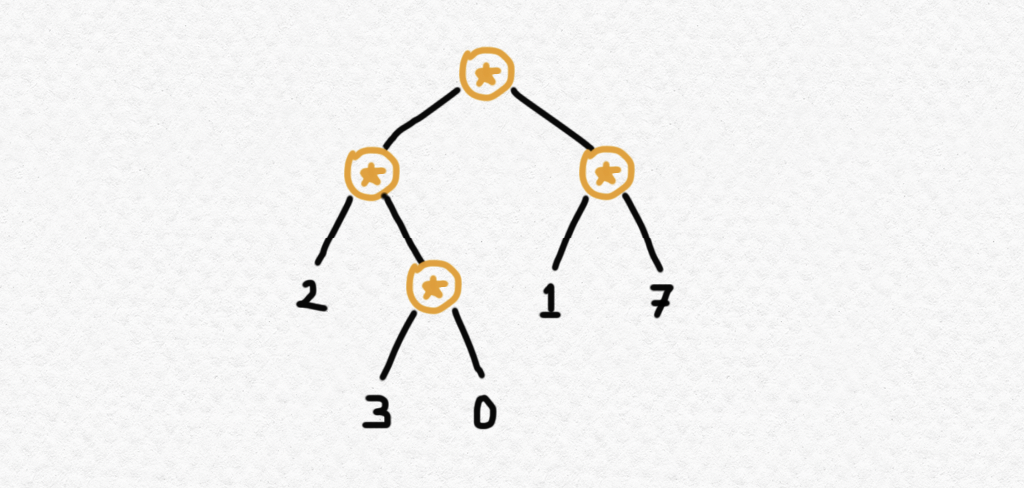

But when dealing with an arbitrary not-necessarily-associative operation, which we'll again call $\star$, more than just the order of the terms matters, so this kind of representation isn't appropriate. That is, using $a\star b\star c\star d\star e$ is ambiguous because it could mean, say, either one of or or any of the other $12$ possible ways of operating together $5$ terms in this order, which could all have different values. (The number of ways to associate $n$ terms being operated together is the nth Catalan number $C_n$, which I discuss briefly in this post.) However, it turns out that nested applications of non-associative operations can be faithfully represented by binary trees, rather than chains, in which each fork of the tree consists of an operation application, and each leaf consists of a term. For instance, the expression would correspond to the following tree:

whereas the expression corresponds to the following tree:

This construction shows how we can think of binary trees with data (taken from a set $A$) at the leaves can be thought of as an unevaluated expression involving nested applications of a binary operation. Since it is left unevaluated and the operation is unspecified, we may store a single tree and evaluate it using different binary operations in place of $\star$. For instance, the tree

which corresponds to the expression evaluates to $13$ if $\star=+$ (addition), evaluates to $0$ if $\star=\times$ (multiplication), and evaluates to $8$ if $\star=~ ^\wedge$ (exponentiation).

We can easily implement binary trees as an inductive data type in Agda as follows:

data BTree (A : Set) : Set where

ℓ : A → BTree A

_⊕_ : BTree A → BTree A → BTree A

where we may think of ℓ as the constructor for a tree consisting of only a single leaf, and ⊕ as a constructor allowing us to produce a new binary tree by "joining together" two preexisting ones at a shared root. Note that this is a parametrized inductive type: it depends on A, the type of the data that will be stored at each leaf node. Now, we can easily write a recursive function to "evaluate" these trees at a given binary operation as follows:

eval-tree : {A : Set} → BTree A → (A → A → A) → A

eval-tree (ℓ a) _ = a

eval-tree (t ⊕ s) op = op (eval-tree t op) (eval-tree s op)

Now we're almost ready to precisely formulate a kind of generalized associativity theorem. We want to show that if a binary tree is evaluated with an associative binary operation, then the final value depends only on the "order" in which the data values occur in the leaves of the BTree A. So our final tool might have a type signature that looks something like this:

generalized-assoc : {A : Set}

→ (T1 T2 : BTree A)

→ (op : A → A → A)

→ is-assoc op

→ list-of-leaves T1 ≡ list-of-leaves T2

→ eval-tree T1 op ≡ eval-tree T2 op

In other words, we claim that if op is associative and trees T1 and T2 have the same "list of leaves", then eval-tree T1 op and eval-tree T2 op will evaluate to the same value. Of course, we have not yet defined is-assoc or list-of-leaves. More on this in a moment.

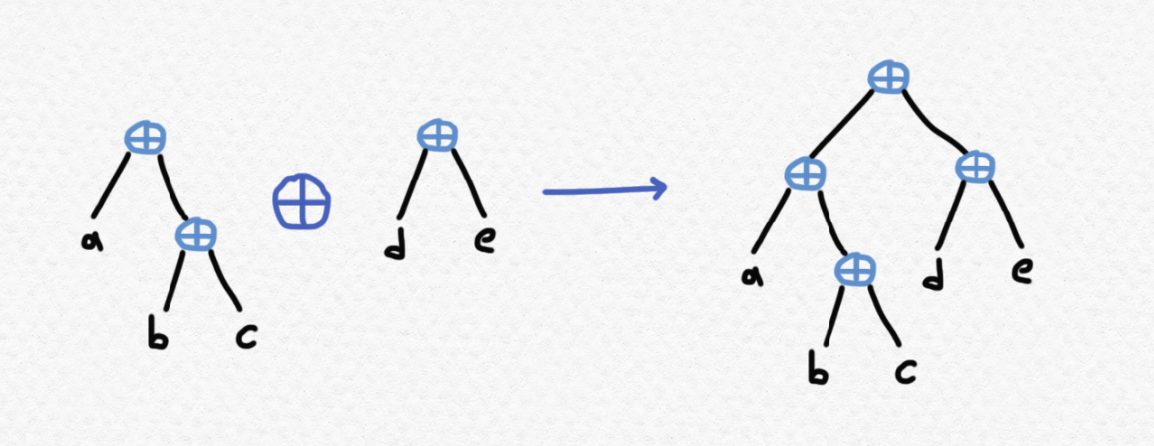

The ⊕ constructor that we have defined on binary trees joins two trees together at the root, like this:

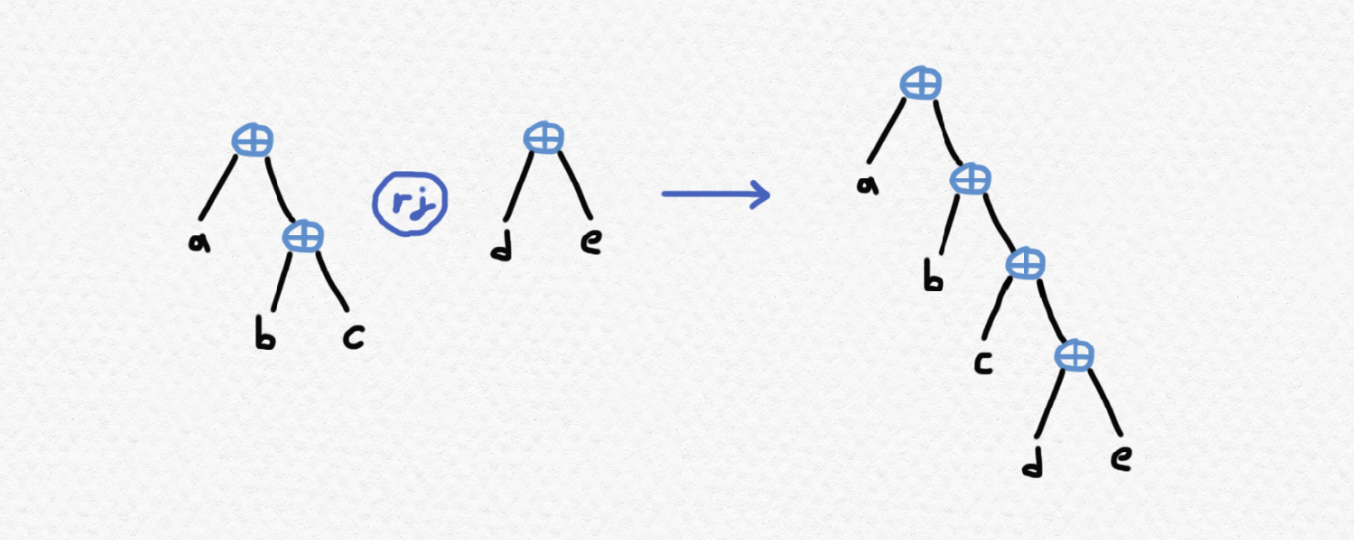

and if we look at how the sequence of leaf values from left to right of T1 ⊕ T2 depends on the sequences of T1 and T2, we can see that it will concatenate these sequences, e.g. concatenating $(a,b,c)$ and $(d,e)$ to form $(a,b,c,d,e)$. Now I would like to define another operation on trees, which we'll call the "right-join" of two trees: when we right-join the tree T1 with T2, we will attach the root of T2 to the right of the rightmost node of T1, like this:

Notice that this operation also concatenates the leaf sequences of T1 and T2. It's pretty straightforward to write a recursive function in Agda to implement this operation, making use of pattern matching:

right-tree-join : {A : Set} → BTree A → BTree A → BTree A

right-tree-join (ℓ a) T = (ℓ a) ⊕ T

right-tree-join (T1 ⊕ T2) T = T1 ⊕ (right-tree-join T2 T)

We only have to consider two cases in evaluating right-tree-join T1 T2: either T1 is a leaf, in which case we simply join T1 and T2 at the root, or T1 is equal to two binary trees joined at the root, in which case we must right-join T2 to the right subtree. Recursively, this step will continue bringing us down the rightmost branch of the tree T1 until we reach a leaf, and then it will join T2 with this leaf.

We're not quite ready to write our general associativity function, but a first step would be to prove that T1 ⊕ T2 and right-tree-join T1 T2 always evaluate to the same thing when evaluated using an associative binary operation, giving us the ability to rearrange trees (in a limited way) without altering the value of their evaluation. Later on, we'll find a way to algorithmically apply this identity many times in succession to prove our final result. But for now, let's just focus on showing that these two ways of combining binary trees are "compatible".

First of all, we haven't even define associativity in Agda yet. Here's how we can define a parametrized type used to express that a binary operation is associative:

is-assoc : {A : Set} → (A → A → A) → Set

is-assoc {A} op = (x y z : A) → op (op x y) z ≡ op x (op y z)

so that an element of type is-assoc op is an associator for the binary operation op : A → A → A, which produces, for any three elements x y z : A, an equality op (op x y) z ≡ op x (op y z). Now, our (intermediate) claim is that given an associative binary operation on a type A and any two trees T1 T2 : BTree A, the evaluations of T1 ⊕ T2 and right-tree-join T1 T2 using op are equal. That is, we are seeking a function (which we will call assoc-⊕-right-join) with the following type signature:

assoc-⊕-right-join : {A : Set}

→ (T1 T2 : BTree A)

→ (op : A → A → A)

→ (is-assoc op)

→ eval-tree (T1 ⊕ T2) op ≡ eval-tree (right-tree-join T1 T2) op

Let's define this using pattern-matching on the first tree. T1 can either be simply a leaf, or the combination of two simpler trees. When T1 is a leaf, the trees T1 ⊕ T2 and right-tree-join T1 T2 are literally the same tree by definition, so the proof is trivial in this case, and we may add the following line to our definition:

assoc-⊕-right-join : {A : Set}

→ (T1 T2 : BTree A)

→ (op : A → A → A)

→ (is-assoc op)

→ eval-tree (T1 ⊕ T2) op ≡ eval-tree (right-tree-join T1 T2) op

assoc-⊕-right-join {A} (ℓ a) T2 op _ = ap (λ x → eval-tree x op) (refl ((ℓ a) ⊕ T2))

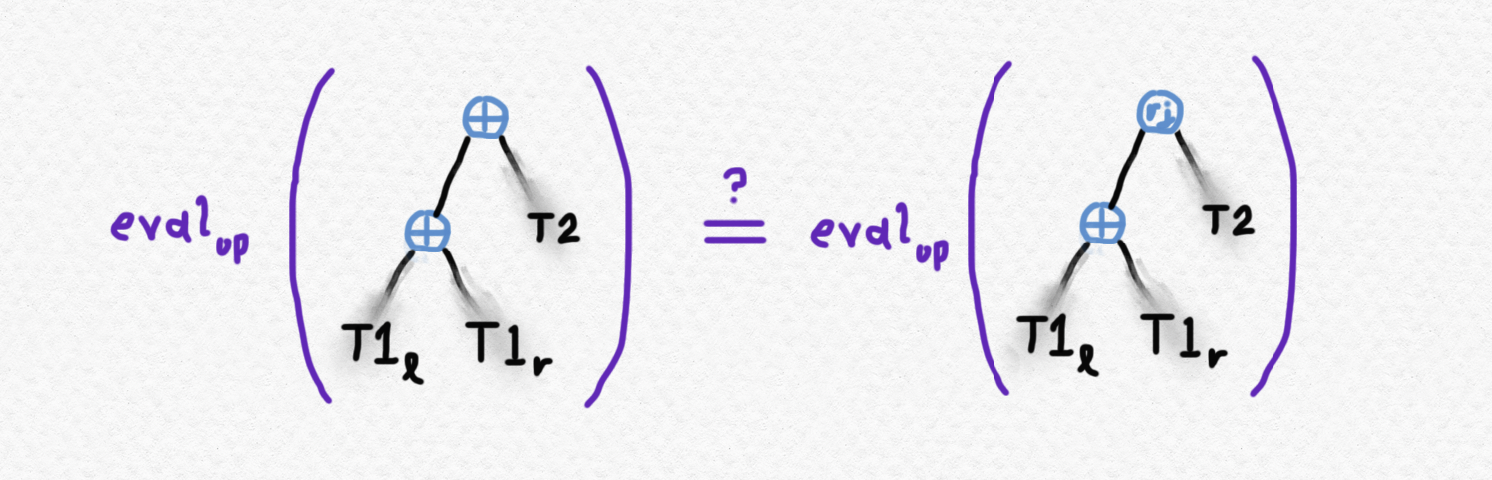

which asserts that since (ℓ a) ⊕ T2 and right-tree-join (ℓ a) T2 are equal as trees, their evaluation using op must be the same. The second case is a little trickier, but it can be proven using the following sneaky manipulations. If T1 consists of two smaller trees T1l and T1r adjoined at the root, we need to show that the following evaluations are equal:

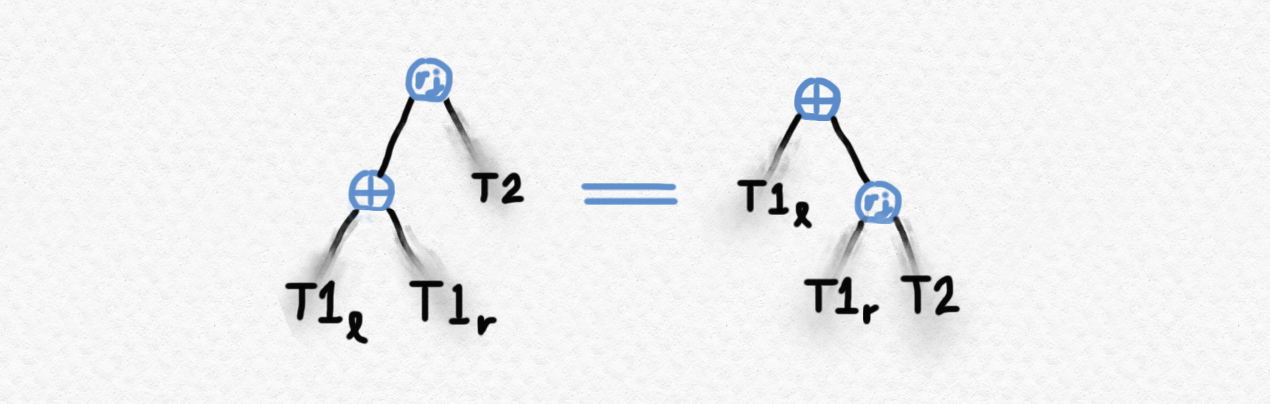

Let's start by looking at the tree on the right-hand side. Recall that, by the definition of the right-tree-join operation (which I'm representing pictorially by the letters "rj" in a bubble), it can always be moved into the right subtree of its left argument. This means that the following trees are equal by the definition of right-tree-join:

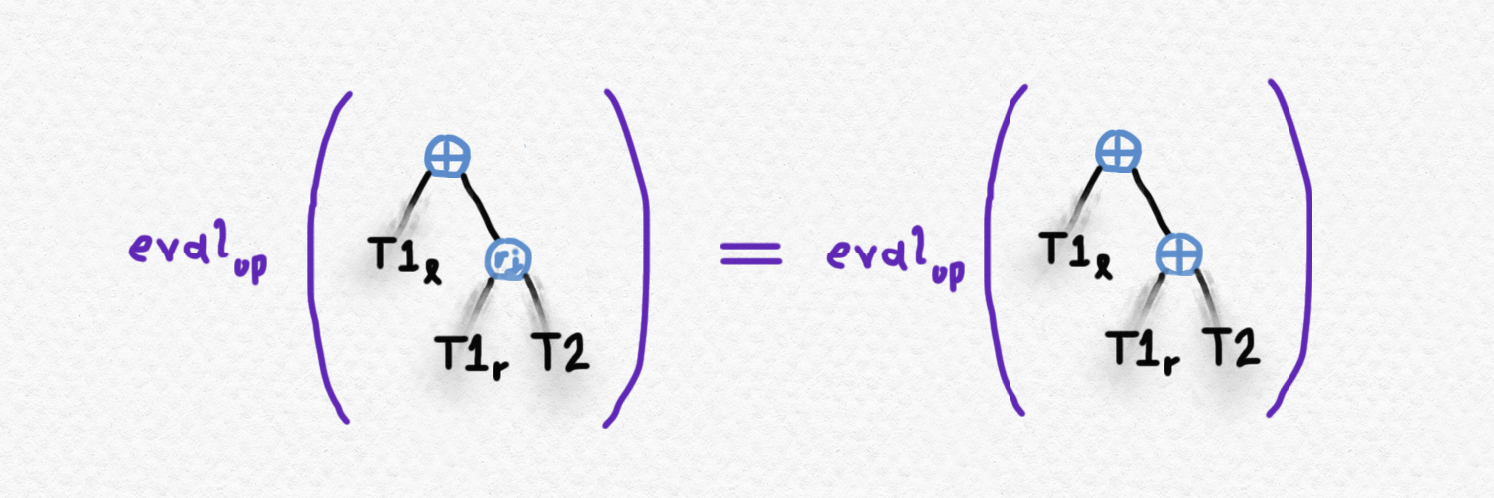

Next, if we already know by (recursively) evaluating assoc-⊕-right-join at the simpler values of T1r and T2 that the evaluation of T1r ⊕ T2 is equal to the evaluation of right-tree-join T1r T2, we have that the right-tree-join on the RHS of this equality can be replaced with ⊕ without affecting the value of the evaluation:

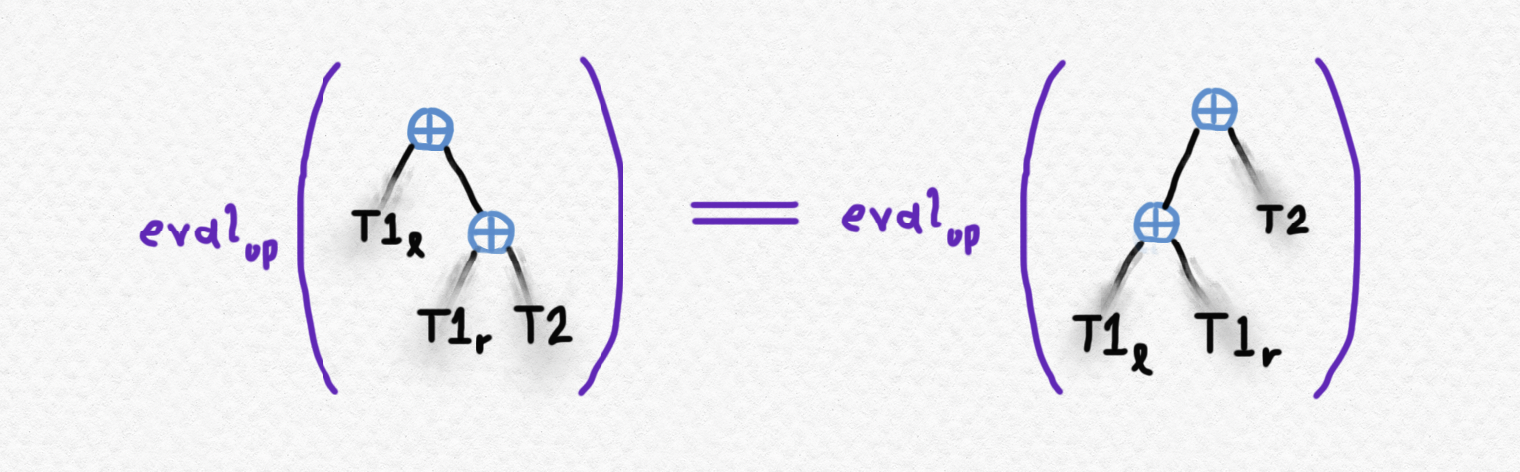

Finally, the associativity of op allows us to show that T1l ⊕ (T1r ⊕ T2) has the same evaluation as (T1l ⊕ T1r) ⊕ T2 or T1 ⊕ T2:

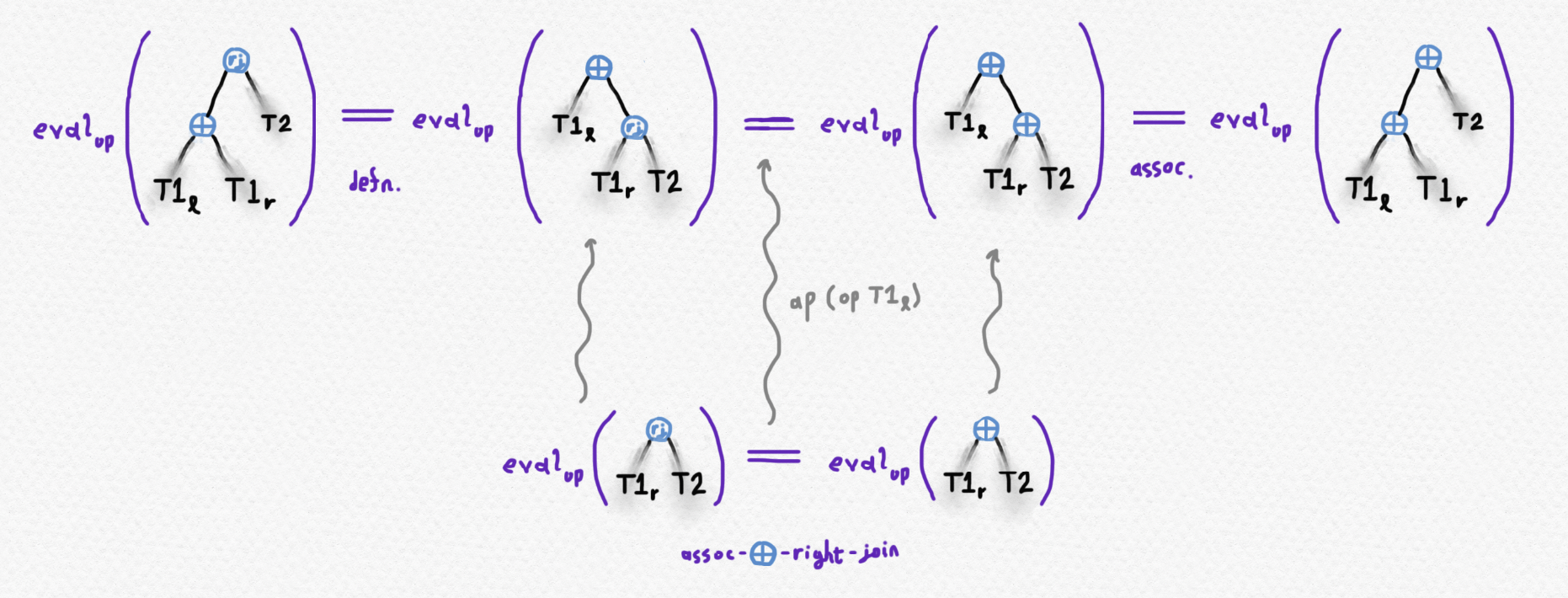

Now we can string all of these equalities together to get the desired result. Here's a picture illustrating how they all fit together:

resulting in the following completed definition of our function:

assoc-⊕-right-join : {A : Set}

→ (T1 T2 : BTree A)

→ (op : A → A → A)

→ (is-assoc op)

→ eval-tree (T1 ⊕ T2) op ≡ eval-tree (right-tree-join T1 T2) op

assoc-⊕-right-join {A} (ℓ a) T2 op _ = ap (λ x → eval-tree x op) (refl ((ℓ a) ⊕ T2))

assoc-⊕-right-join {A} (T1l ⊕ T1r) T2 op ass = transeq

(ass

(eval-tree T1l op)

(eval-tree T1r op)

(eval-tree T2 op)

)

(ap (op (eval-tree T1l op))

(assoc-⊕-right-join T1r T2 op ass))

Now we know that T1 ⊕ T2 and right-tree-join T1 T2 always have the same evaluation under an associative binary operation. Not only does this mean that right-joining the left and right subtrees of a tree will leave its evaluation unchanged, but performing this manipulation on any subtree will also have no effect on the final value. In fact, since a binary tree just consists of a bunch of leaves (ℓ a) combined using ⊕, we could even replace every instance of the _⊕_ constructor with the right-tree-join operation. We can easily write a function that does this recursively:

fold-right-join : {A : Set} → BTree A → BTree A

fold-right-join (ℓ a) = ℓ a

fold-right-join (T1 ⊕ T2) = right-tree-join (fold-right-join T1) (fold-right-join T2)

Applying this function to a tree will result in a tree whose leaves are in the same order, but which is "right-heavy", such that the left-child of any node is just a leaf. Since we have just shown that the evaluations of T1 ⊕ T2 and right-tree-join T1 T2 always coincide, it is not difficult to show that T and fold-right-join T have equal evaluations for any tree T (provided the operation is associative) by applying this function recursively to every subtree:

assoc-reduce-right-tree : {A : Set}

→ (T : BTree A)

→ (op : A → A → A)

→ (is-assoc op)

→ eval-tree T op ≡ eval-tree (fold-right-join T) op

assoc-reduce-right-tree (ℓ a) _ _ = refl a

assoc-reduce-right-tree (T1 ⊕ T2) op ass = transeq

(eq-eq-opeq

op

(assoc-reduce-right-tree T1 op ass)

(assoc-reduce-right-tree T2 op ass)

)

(assoc-⊕-right-join

(fold-right-join T1)

(fold-right-join T2)

op

ass

)

and this has the convenient consequence that not only does each tree have the same evaluation as the "right-heavy" tree whose leaves are in the same order, but also if two trees have leaves in the same order, their reduction to "right-heavy" trees will be the same, and therefore their evaluations will both be equal to the evaluation of that right-heavy tree and therefore equal to each other. This fact is encapsulated in the following function, which adds little more than a simple application of transitivity to the previous function:

assoc-reduction-eval : {A : Set}

→ (T1 T2 : BTree A)

→ (op : A → A → A)

→ is-assoc op

→ (fold-right-join T1 ≡ fold-right-join T2)

→ eval-tree T1 op ≡ eval-tree T2 op

assoc-reduction-eval T1 T2 op ass eq = transeq

(assoc-reduce-right-tree T1 op ass)

(transeq

(ap (λ t → eval-tree t op) eq)

(inveq (assoc-reduce-right-tree T2 op ass))

)

That's it - we've done it! Now let's see a quick example of how to actually use this theorem to save us some tedium in Agda. Suppose we've already proven that + is an associative operation on $\mathbb N$ (which we've done in the previous post) and we want to show the following identity: Rather than painstakingly keeping track of each association that needs to take place and repeatedly using ap to generate the necessary equalities to be chained together, we can just make use of the fact that the left-hand side is the same as eval-tree ((((ℓ w) ⊕ (ℓ x)) ⊕ (ℓ y)) ⊕ (ℓ z)) _+_ and the right-hand side is the same as eval-tree ((ℓ w) ⊕ ((ℓ x) ⊕ ((ℓ y) ⊕ (ℓ z)))) _+_. Then we can let our function assoc-reduction-eval do the work - we just need to supply it with a proof that addition is associative. Here's a proof of the desired identity:

+assoc4 : (w x y z : ℕ) → (((w + x) + y) + z) ≡ (w + (x + (y + z)))

+assoc4 w x y z = assoc-reduction-eval

((((ℓ w) ⊕ (ℓ x)) ⊕ (ℓ y)) ⊕ (ℓ z))

((ℓ w) ⊕ ((ℓ x) ⊕ ((ℓ y) ⊕ (ℓ z))))

_+_

(λ m n p → inveq (plus-assoc m n p))

(refl _)

If you've been following along, you can verify yourself that this typechecks in Agda! You might wonder why, for the argument of type fold-right-join T1 ≡ fold-right-join T2 to the function assoc-reduction-eval, we were able to get away with just passing (refl _). Don't we have to do any work to show that these two trees have the same fold-right-join value? The answer is no, we do not - since we defined fold-right-join as a recursive function on the inductive type BTree A, Agda can simply do the computation for itself and check that the two trees are the same! This is the real power of what we've done - by showing that a tree can be reduced to a standardized "right-heavy" form without affecting its evaluation, we can offload the tedious grunt work of actually computing this standard form onto Agda. And not only does our function work for addition, but we can apply it to any operation (say, multiplication) that we are able to prove associative, so we don't have to redo these repetitive proofs every time we introduce a new associative operation. Cheers!