2018 August 25

In a previous post about Dirichlet Series, I referenced some properties of a few arithmetic functions like $\tau$, the divisor-counting function, $\sigma$, the divisor sum function, $\varphi$, the Euler totient function, $\mu$, the Mobius mu function, and $\sigma_a$, the generalized divisor sum function. Many of these statements went without proof in that post, so in this post I will prove them, along with some other properties of each of these functions.

Let's start with $\sigma_a$, the generalized divisor sum function, as well as $\tau=\sigma_0$ and $\sigma=\sigma_1$. This is defined as ...where the sum is taken over all of the divisors of $n$, the input. For example, if $p,q$ are distinct primes, then An essential property of these functions is that they are multiplicative; that is, that if $m,n$ are two coprime natural numbers, then $\sigma_a(mn)=\sigma_a(m)\sigma_a(n)$. This is pretty easy to prove, using the following property of sums: If $m,n$ are coprime, then each divisor of $mn$ can be written uniquely as the product of a divisor of $m$ and a divisor of $n$. Thus, using the product of summations formula, we have Because $\sigma_a$ is multiplicative, we may obtain a formula for $\sigma_a$ as a finite product using the prime factorization of its input. Note that if $p$ is a prime, then Thus, if $n$ has the prime factorization then we have that where the product is taken over all primes $p$ dividing $n$, and their respective multiplicities $k$.

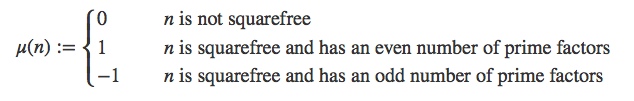

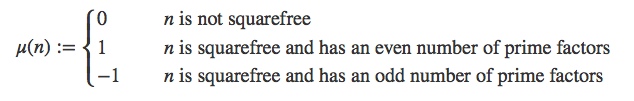

Now let's move on to $\mu$, the Mobius mu function. It has a piecewise definition:

It's easy to show that $\mu$ is multiplicative as well. If $m,n$ are positive integers and one of $m,n$ is divisible by a perfect square other than $1$, then their product clearly is as well; thus, if $\mu(m)\mu(n)=0$ then $\mu(mn)=0$ and $\mu(mn)=\mu(m)\mu(n)$. If neither $\mu(m)$ nor $\mu(n)$ is $0$, then we must do a bit of casework. If they are coprime, their sets of prime factors are disjoint, so if the parities of their cardinalities are distinct, then the parity of the cardinality of their union is odd; otherwise, the parity of the cardinality of their union is even. These correspond to the identities $1\cdot 1=1$, $(-1)\cdot (-1)=1$, and $1\cdot (-1)=-1$, establishing the multiplicativity of $\mu$.

Many of the interesting identities of $\mu$ are related to arithmetic sums, but this will be the topic of the next blog post.

Finally, consider the function $\varphi$, or the Euler Totient Function. $\varphi(n)$ is defined as the number of positive integers less than and relatively prime to $n$. Proving the multiplicativity of $\varphi$ is the most difficult, and it requires some previous knowledge about $\mathbb Z_m$, the additive group of integers modulo m.

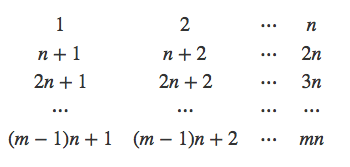

Suppose $m,n$ are coprime positive integers. Arrange all of the positive integers from $1$ to $mn$ in a table with $n$ columns and $m$ rows, as shown below:

The numbers in the $c$ th column are in the form $bn+c$, so if $c$ is not coprime to $n$, since all common divisors of $c,n$ must also divide $bn+c$, we have that all numbers in the $c$ th column are not coprime to $n$, and are thus not coprime to $mn$.

So let us consider only the columns $c$ for which $c$ is coprime to $n$, noticing that the number in the $b$ th row and $c$ th column is $bn+c$. Because all of these numbers are coprime to $n$ as long as $c$ is coprime to $n$, and because $mn$ is coprime to any number as long as that number is coprime to both $m$ and $n$, we must figure out how many of the numbers in each column are coprime to $m$.

Now I shall use the fact that if $a$, an integer, is coprime to $m$, then multiplying each element of $\mathbb Z_m$ by $a$ and taking the remainder modulo $m$ still results in the set $\mathbb Z_m$; similarly, adding any number to all elements of $\mathbb Z_m$ and taking modulo $m$ results in $\mathbb Z_m$. This means that, modulo $m$, the elements in any two columns are exactly the same up to rearrangement, since the elements in any column consist of the elements of $\mathbb Z_m$ multiplied by $n$ (which is coprime to $m$), plus a constant. Since a number is coprime to $m$ if and only if its residue modulo $m$ is coprime to $m$, we have that the number of elements of any column of the grid coprime to $m$ is equal to the number of elements of $\mathbb Z_m$ that are coprime to $m$. This is precisely $\varphi (m)$, by definition.

Thus, we have that there are $\varphi(m)$ numbers coprime to $m$ in each column, and all numbers in each of $\varphi(n)$ columns are coprime to $n$; thus, since a number is coprime to $mn$ if and only if it is coprime to $m$ and $n$, we have that there are $\varphi(m)\varphi(n)$ numbers coprime to $mn$ in the grid, and so $\varphi(mn)=\varphi(m)\varphi(n)$ as desired.

We may find an interesting product representation for $\varphi(n)$ using its prime factorization, similarly to how we did for $\sigma_a$, using the trivial fact that for $k\gt 0$. We have that if the prime factorization of $n$ is Then ...where the product is taken over all primes $p$ dividing $n$.

That concludes this short post! The next post will hopefully be much longer and more interesting, and it will be about the evaluation of certain finite arithmetic sums involving these functions.