2017 April 9

Find the formula for the nth iterate of the function $f(x)=2x^2-1$ for $|x| \le 1$. Find the formula for the nth iterate of a quadratic with a fixed point at its minimum.

It seems that some polynomial functions, such as $f(x)=x^2+1$, simply can't have an iteration formula in the closed form. However, some do because they can be put in the form $f(x)=(g\circ h\circ g^{-1})(x)$. For example, any polynomial function of the form

can be iterated, because it takes the aforementioned form with

meaning that

Let's apply this to quadratics. This formula tells us that any quadratic with its vertex on the line $y=x$ can be iterated by this formula, because a quadratic with its vertex on $y=x$ takes the form

or

Which we can see takes the form $f(x)=(g\circ h\circ g^{-1})(x)$ where $g(x)=\frac{1}{a}x+h$ and $h(x)=x^2$, so

That's about it for polynomials, aside from a few quadratics that can be iterated somewhat using trigonometric functions. For example, the quadratic

can be split up into

which, once again, takes our special form and can be iterated as

However, quadratics iterated this way can only be iterated to a certain extent because of the limited domain of the inverse trigonometric functions. Let's try an example anyways. What about $f^{10}(0.5)$? Using our formula, this will be

Well, that was a bad example to try, because $f(0.5)=f(-0.5)=-0.5$, so we could have found that without our formula. How about $f^{10}(0.1)$?

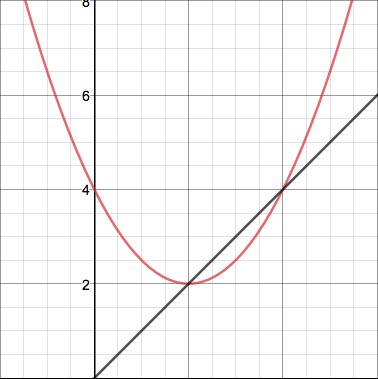

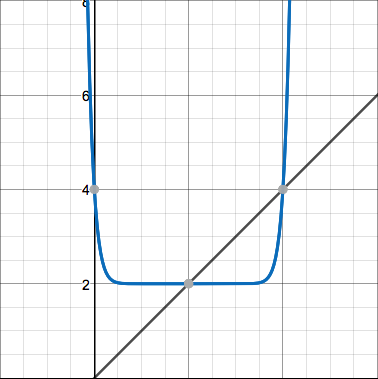

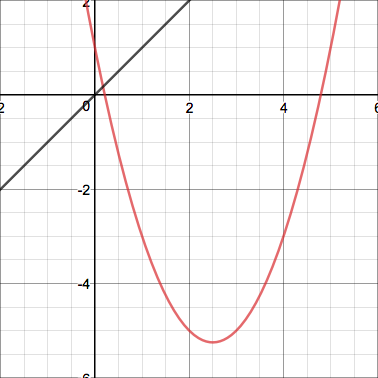

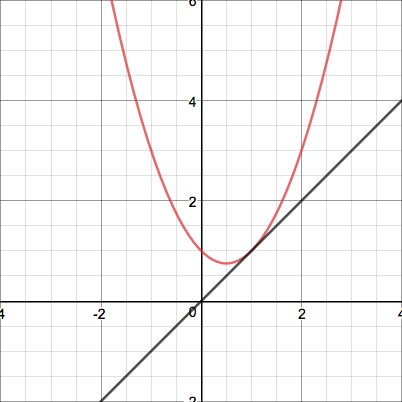

I think I'm noticing a pattern here. When I iterate a quadratic whose vertex is on $y=x$, the graphs of the iterates exhibit predictable behavior. Here are the graphs of $y=\frac{1}{2}(x-2)^2+2$ and its first few iterates:

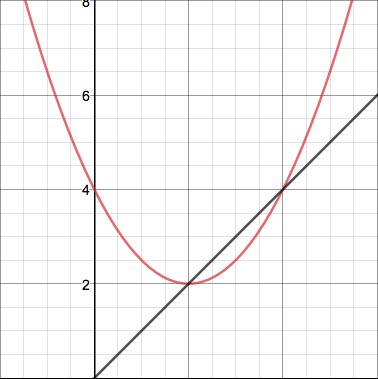

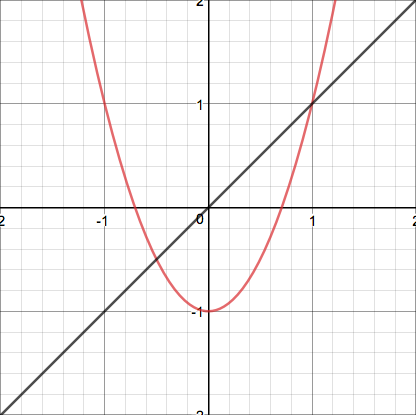

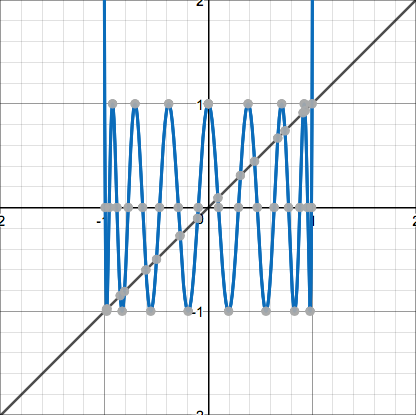

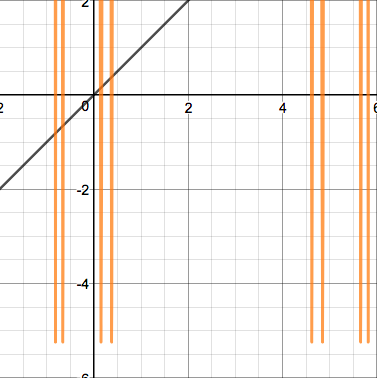

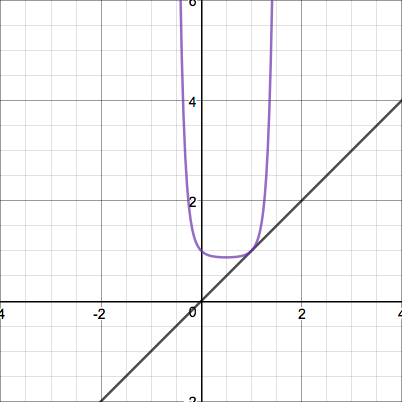

They all seem to predictably flatten out at the bottom and then become steeper more and more quickly. Now here's the function $f(x)=2x^2-1$ and its first couple iterates:

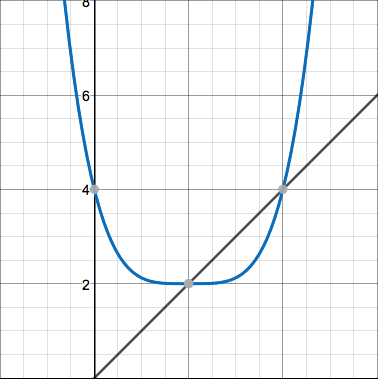

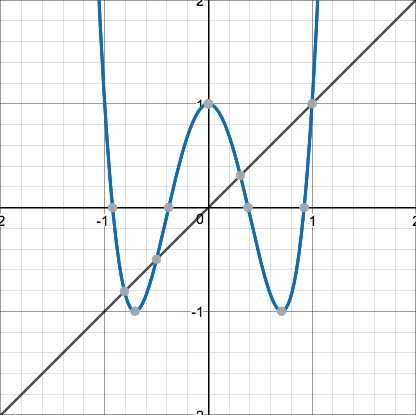

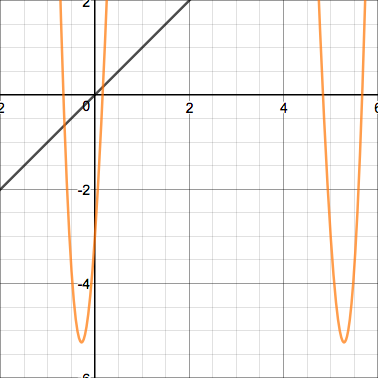

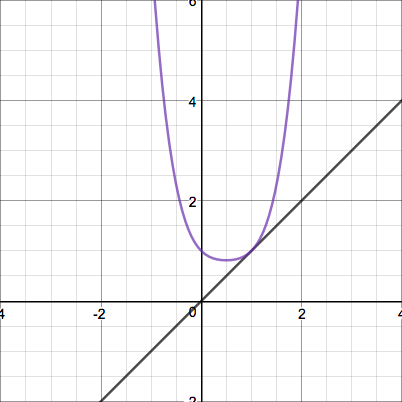

These display neat sinusoidal behavior and then head straight up. In fact, the crests of each of the waves are at a height of $1$, and the points $(1,1)$ and $(-1,1)$ lie on the curve directly before and after it begins to grow out of control, which is perhaps the reason why we cannot iterate it outside of that interval. Now observe these pictures of a quadratic of neither form:

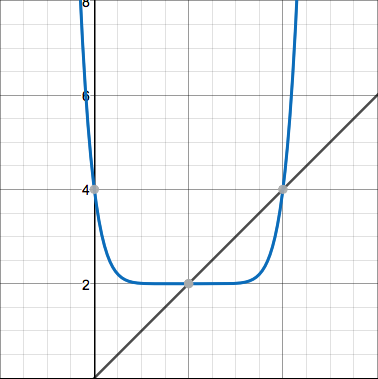

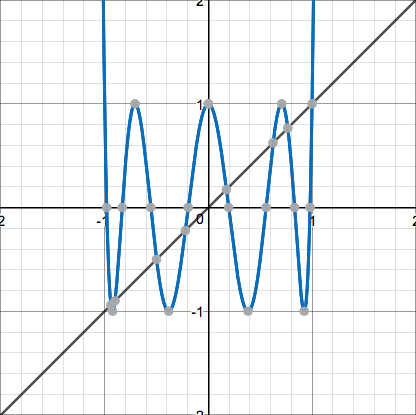

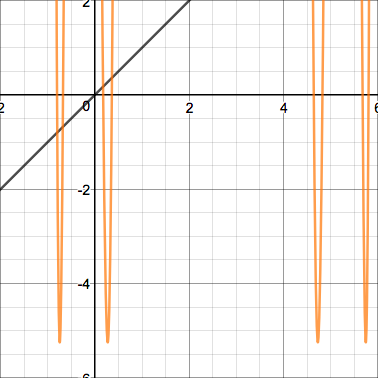

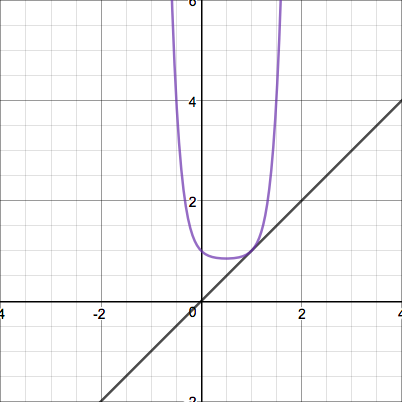

This quadratic's iterates display erratic behavior that grows insanely large before coming down again. Here's one more interesting case - a parabola tangent to the line $y=x$:

Perhaps there is some formula for quadratics of that form, since they seem to behave predictably... but that's for another post.