Lately I've been an active contributor to Tatoeba, a huge open-source collection of parallel sentences in many different world languages. Aside from being an amazing resource for the languages I'm studying, it's given me exposure to languages that I didn't even know existed before, and it's also a great dataset for NLP projects.

I've been mulling over the following question: given a bunch of example sentences translated into your own language, would it be possible to algorithmically deduce translations for individual lexemes/morphemes? When done manually, this task is fairly simple. For instance, I don't know any Hungarian, but if I were given the following Hungarian translations of English sentences:

| English | Hungarian |

|---|---|

| Tom filled the bottle with drinking water. | Tom megtöltötte az üveget ivóvízzel. |

| Tom drinks at least three liters of water every day. | Tom naponta legalább három liter vizet iszik. |

| If it weren't for water, humans wouldn't survive. | Ha nem lenne víz, az emberek nem élnék túl. |

| The water came up to our knees. | A víz térdig ért. |

| I would like some water. | Kérek egy kis vizet. |

...then after staring at these sentences for a while, I would be able to guess that the word for water in Hungarian is víz without any prior knowledge. This is because the only thing in common between the English sentences is the word water, whereas for the Hungarian sentences it seems to be víz or viz (sometimes with additional prefixes/suffixes). In fact, I would also be willing to guess that ivóvízzel means drinking water.

Really, all I did was look at these sentences, find some common subsequences of characters, and make a heuristic judgment about what the most likely translation of the word water would be. This process seems like it should be susceptible to automation, so I gave it a try!

Most of the NLP tools and algorithms that I've learned about are for processing text at the word/morpheme level, and presuppose a tokenizer/lemmatizer/stemmer for the target language. This task, however, occurs at the character level and concerns how we discover lexemes/morphemes in the first place. I'm not familiar with many NLP techniques that work at this low of a level, so this problem has been a very fun challenge!

Below, I explain my approach and discuss some of its current weaknesses.

But first, a little eye candy!

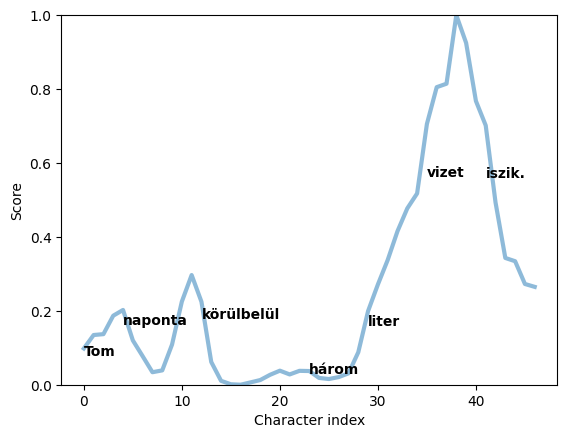

Given a list of sentences in a target language with a word/phrase/substring in common between their English translations, my code calculates a kind of "heatmap" on each sentence, assigning each position in the sentence a score between 0 and 1 quantifying its local similarity to other sentences. We can visualize the results for specific sentences by graphing the scores by character index. Here's an example in Hungarian, generated when searching for a translation of the word water:

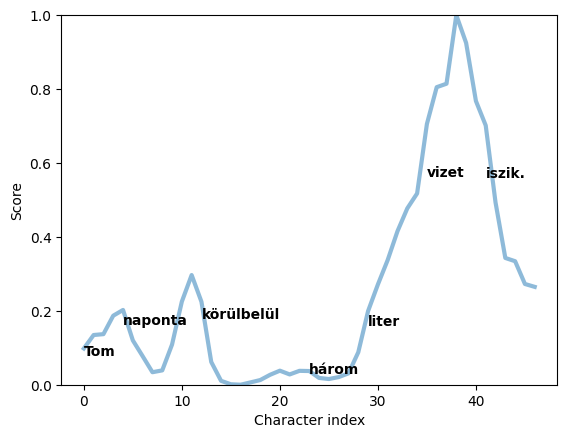

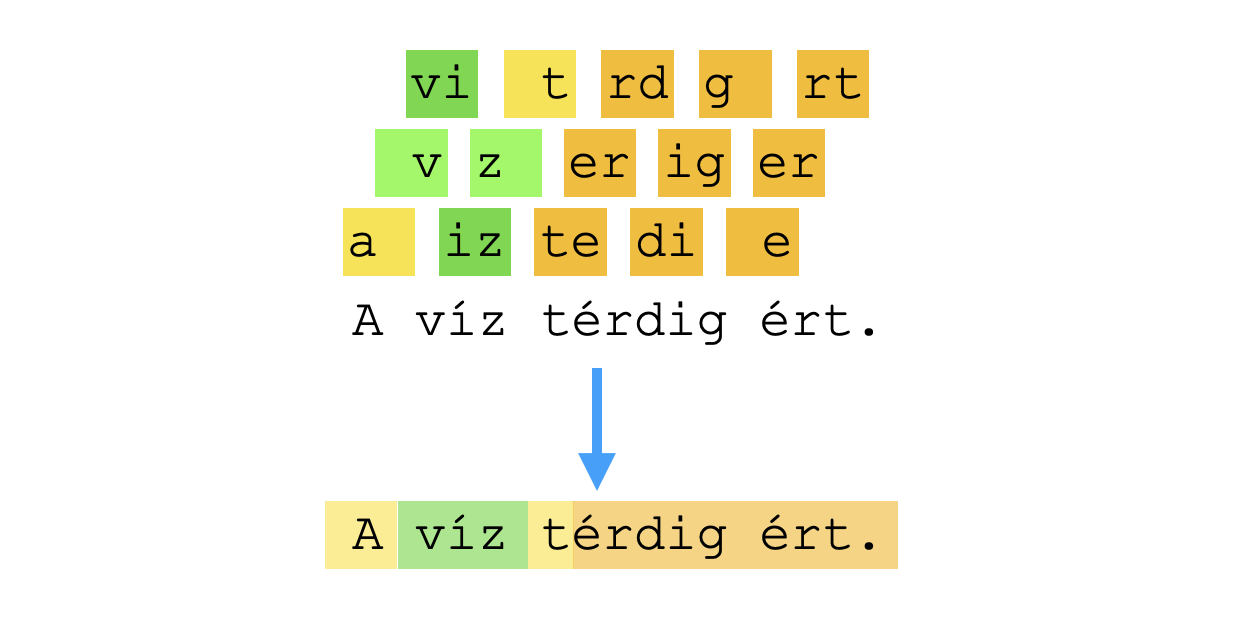

I also have a utility for visualizing this "relevance score" by highlighting segments of sentences in the target language with varying levels of saturation. Here's what this looks like for the same example in Hungarian:

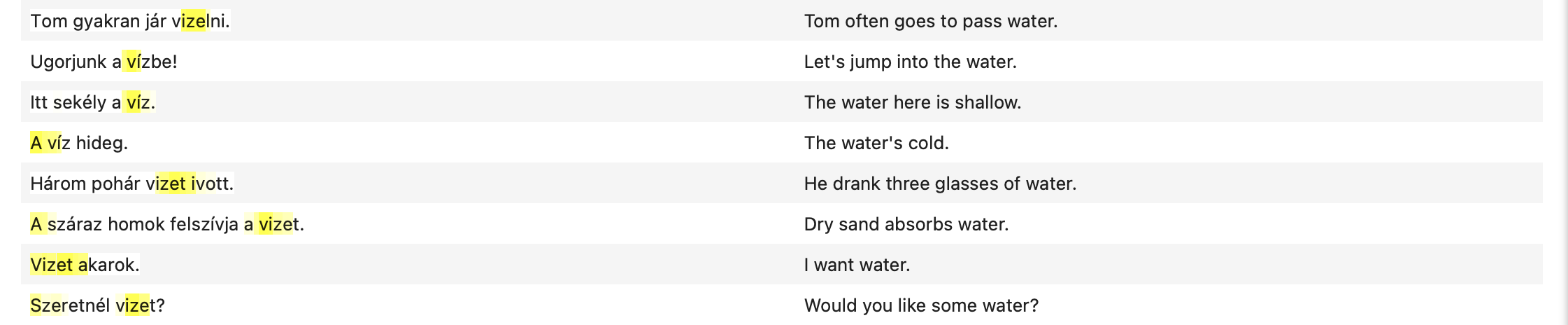

Candidate words can be obtained from sentences by extracting segments containing the highest scores. By defining a custom string distance metric on the extracted strings and performing hierarchical clustering, we can also obtain a heuristic grouping of the words into clusters comprising possible lexemes. These clustered words or word forms can then be visualized as a dendrogram. Here's a dendrogram output by my code for the same example in Hungarian:

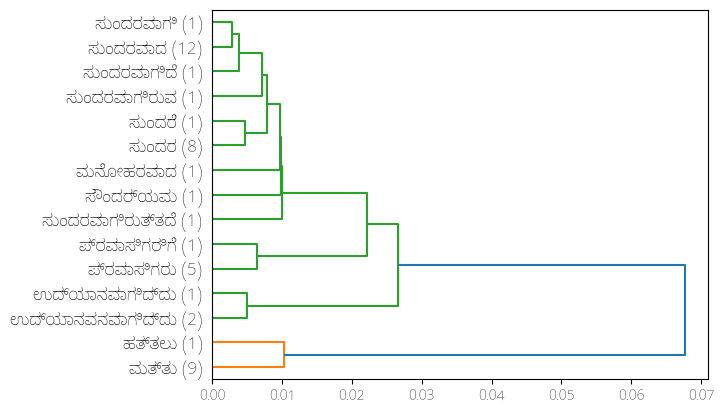

Although most of my test runs have used parallel sentences from Tatoeba, data can be ingested from any TSV-formatted file of parallel sentences. I was also able to import some data in Kannada (a Dravidian language spoken in India) from the Anuvaad Parallel Corpus and test out my algorithm on it. Here's the resulting dendrogram when I asked it to infer possible translations for the word beautiful:

Jump to the end of the post for a huge table of examples showing lexeme guesses for a few very common words in several different languages. Though my code is still pretty rough around the edges, I'm very happy with how the results are coming out so far, and I wonder if it has the potential to be developed into something more sophisticated like an unsupervized best-effort lemmatizer for languages lacking established lemmatization tools.

If you're interested, you can check out my code in a Jupyter notebook here on Github. I encourage you to play around with it! Parallel sentence data from several sample languages is included in the repo, so no additional downloads (aside from Python packages) should be necessary.

Now, here's a more in-the-weeds description of my approach.

The problem under consideration is as follows: given a bunch of sentences in language $L$ whose translations contain a certain word $w$ (or more generally, matching a certain regex), produce one or more "candidate morphemes" in the language $L$ that might serve as translations of $w$. I'm calling this problem "unsupervised" because I'm not using ground truth data (such as dictionaries in various languages) to train any sort of model to recognize words.

My first thought was to use an n-gram model to analyze common sequences of characters in example sentences. Given a set $S$ of sentences in language $L$ with translations containing the target word $w$, we could tabulate the frequencies of 2-grams or 3-grams among those sentences. Then the "hottest" substrings in each sentence could be identified as the ones containing more high-frequency n-grams on average.

I implemented this approach and it worked shockingly well for many languages. However, there was a huge drawback for languages like Arabic and Hebrew that have non-contiguous word roots. For instance, in Hebrew, the word for to read has the 3-letter root קרא, and conjugating this verb sometimes involves inserting letters in between: he reads becomes קורא, inserting the letter ו. This is a big problem for the n-grams approach, because when scoring these words in a collection of sentences, the 2-grams קר and קו would compete with each other in the 2-gram frequency count, causing different conjugations of to read to detract from each others' scores.

My immediate next thought was to use an generalized version of n-grams called "skip-grams", in which both contiguous and non-contiguous letter combinations are tabulated, e.g. there might be a frequency category not only for the substring קר, but also an additional category for occurrences of ק and ר separated by one or fewer characters, or by two or fewer characters, and so on. The problem with this approach is that the number of possible categories grows very quickly and it's not obvious what kind of scoring system should be used to take them all into account.

The idea I'm about to describe occurred to me at around midnight one night, and I ended up staying up until about 3am frantically coding up a proof-of-concept - I had to know if it would work! Vector embeddings were fresh in my mind because of a recent online course in NLP, but I had never seen a vector embedding technique applied to individual characters rather than words.

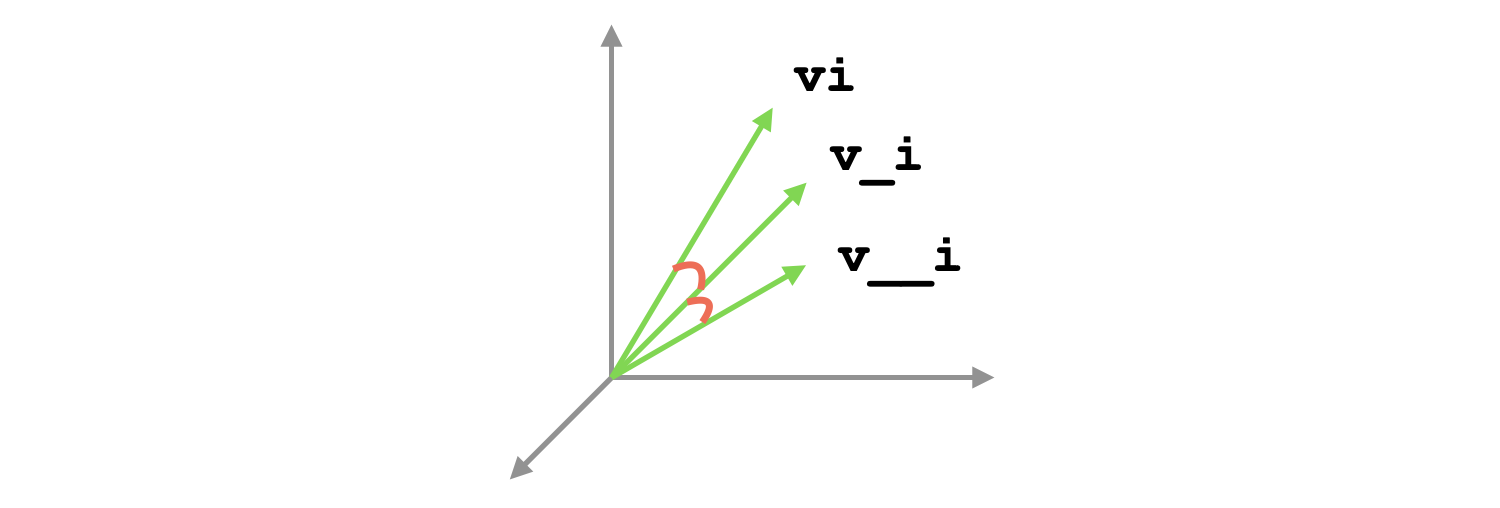

Say $C$ is the set of all characters in the language $L$. These characters might be normalized to avoid distinguishing characters that are "really the same", e.g. capitalized versus lowercase versions of the same letter, or accented versus non-accented variants, etc. Each character $c\in C$ is assigned a unit vector $\phi(v)\in \mathbb R^d$ where $d$ is the dimension of the embedding. These embeddings should either assign orthogonal vectors to different characters (in which case we must have $d\ge |C|$) or very nearly orthogonal vectors to different characters (in which case you can often do with fewer than $|C|$ dimensions). This ensures that different characters are handled independently.

Once we have a character embedding, we define a way of embedding pairs of characters separated by a certain number of indices in a string. This can be defined by a function $\psi:C^2\times {0,\cdots,\ell}\to\mathbb R^d$, where $\psi(c_1,c_2,j)$ is the embedding for $c_1$ followed by $c_2$ after $j$ characters, and $\ell$ is the "lookahead value" determining the maximum level of separation represented by the embedding. I've experimented with a few different options for this embedding, but the general idea is that $\psi(c_1,c_2, i)$ and $\psi(c_1,c_2, j)$ should be somewhat similar to each other, especially when $i,j$ are close, in order to allow embeddings of the same character $c_2$ in slightly different positions after $c_1$ to "constructively interfere" with each other. In this way, $\psi$ acts sort of like a "fuzzy" n-grams frequency table that avoids huge proliferation of frequency categories by allowing some of them to conflate with each other. Further, $\psi(c_1,c_2,i)$ and $\psi(c_1,c_3,j)$ should be orthogonal or near-orthogonal when $c_2\ne c_3$.

One option I've tried has been and another is the following, where $U$ is a unitary matrix that is close to the identity and $\alpha < 1$ is some constant: Both of these work pretty well, but I suspect that the results can be improved by more intelligently designing the function $\psi$, and this is a detail I want to continue experimenting with.

Next, we define a function $\Psi$ such that $\Psi(i, s)$ gives an embedding combining the character pair embeddings $\psi(s[i], -, -)$ for several of the characters following $s[i]$, up to the character $s[i+\ell]$ at the lookahead threshold: And then, given a whole collection of sentences $S$, we define a combined embedding $\overline{\Psi}(c)$ that, intuitively speaking, summarizes the "average context" of the character $c$ in all of the places it appears in all the sentences of $S$. It is defined as follows:

This is an average of all of the embeddings $\Psi(j, s)$ of the positions where the character $c$ appears across all sentences, averaged across different appearances of the character $c$ in each sentence $s$. Making this an average rather than a sum is vital, both because it prevents extremely long sentences from affecting these embeddings disproportionately, and because it prevents high-frequency characters from having much larger embeddings in general. It is also multiplied by a scaling factor punishing characters that occur only in a small number of the sentences in $S$.

Finally, for each sentence $s$ in $S$, each of its characters is scored by calculating the cosine similarity of each character's local embedding in that specific sentence with its global embedding across all of the sentences in $S$. That is:

When a character is followed by sequences of characters that frequently follow it in many of the sentences in $S$, then the vectors $\overline{\Psi}(c, S)$ and $\Psi(i, s)$ should point in similar directions, meaning that $\text{score}(i, s)$ should be larger.

In my scripts, I also apply some final post-processing to the character scores $\text{score}(i, s)$ for each sentence. For one, I scale and translate the scores into the interval $[0,1]$ by subtracting the minimum score and scaling by the difference between the min and max scores. I also smooth the scores across each sentence by taking a windowed average, and apply a power function such as $x\mapsto x^4$ because it accentuates the difference between higher and lower scores. This is how we get the "heatmap" highlighted sentences and graphs showcased earlier. Extracting the words occurring at the peaks of these graphs is how relevant words are extracted from sentences.

This technique still has several kinks that need to be worked out. For instance, in its current form, it does not distinguish subsequences that are common within a certain subset of sentences from subsequences that are common throughout the language as a whole. For that reason, the results of the above process often contain some irrelevant high-frequency strings corresponding to common words similar to the, a/an and I in English, for example. The same goes for the names Tom and Mary, which are extremely common in the Tatoeba corpus (to the point of being an inside joke of the Tatoeba community). Perhaps character scores could be modified by penalizing characters whose local embeddings are too similar to their global embedding in the language as a whole.

On a similar note, even if a certain word is not common in the language as a whole, it may co-occur very commonly with the target word. Consider for instance the words read/reads/reading and book. Naturally, they co-occur in a lot of the English sentences of the Tatoeba corpus, so that this technique might be likely to, say, mis-identify the Hungarian word for book as an appropriate translation of to read. I still haven't made up my mind about how to remedy this issue.

Finally, there is a key type of deduction that we use easily when manually inferring words' meanings, but my vector method does not take advantage of. Let me illustrate it with another example. Consider the following parallel sentences in English and Latvian. From these sentences, can you guess a translation for the word milk?

| English | Latvian |

|---|---|

| No, I never drink coffee with milk. | Nē, es nekad nedzeru kafiju ar pienu. |

| Boris never confronted Rima. | Boriss nekad nestājās pretī Rimai. |

| Don't drink alcohol. | Nedzeriet alkoholu. |

| I didn't drink any coffee today. | Es šodien nedzēru kafiju. |

| Do you actually like your coffee with salt? | Vai jums tiešām garšo kafija ar sāli? |

| No, I can't. | Nē, es nevaru. |

You could probably infer that pienu means milk even though it only appears in one of these sentences. This is because the remaining words in that sentence also appear in at least one of the other sentences, but milk does not appear in any of their English translations. That is, we have applied a process of elimination to deduce a translation for the word milk, which is a heuristic that my code does not (yet) attempt to use.

To sum up, the things I'd still like to improve, in brief, are:

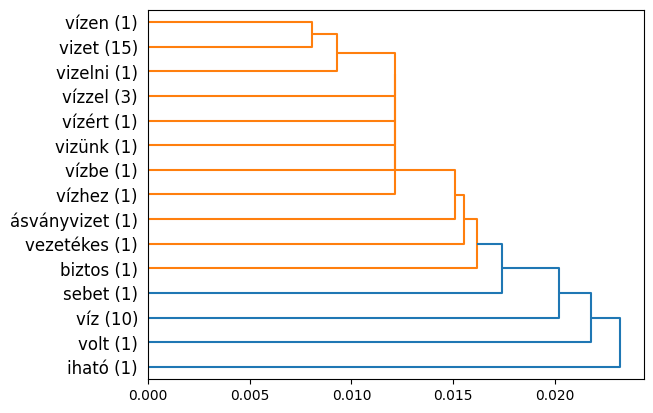

Here's a big fat table showing my algorithm's output for a few common words in several different languages, in case you would like to get a feel for how well it works and the kinds of errors it makes. I recommend Wikitionary for looking up the meanings of these words if you want to check their definitions for accuracy.

| dog | cat | book | bread | water | milk | home | day | eat | sleep | read | black | white | big | small | |

| ber (Berber) | aydinni uydinni aydi aydia uydi aydinneɣ aydinnek aydinnes aydiinu weydi | amcicnni umcicnni amcica amcic umcic amuccnni amcicinu imucca yimucca imcac | adlisnni udlisnni idlisen yidlisen adlis adlisa yedlisen adlisnnes adlisinu udlis | aɣrum uɣrum weɣrum aɣrumnni uɣṛum aɣrumnnes weɣrumnni weɣruminu aqbur ara | waman wamana aman watay yeḥman amanaya amannni amandin mani ameqqran | akeffay akeffaya ukeffay akeffaynni ukeffaynni ukeffayis akeffaynnek ayefki uyefki yefkaiyid | ɣer ɣef deg seg yedda yebda yella yelli taddart tamaneɣt | wass ass assa wussan ussan ussana asmi assnni assnsen yessen | isett nsett ttetteɣ ttetten setteɣ setten teččed teččeḍ iḥemmel ikemmel | teṭṭes yeṭṭes neṭṭes yeṭṭsen yeḍḍes teṭṭseḍ teṭṭsed yettaṭṭas yelzem yiḍes | yeqqar yeqqard yeɣra yeɣrad yeɣri adlis adlisa udlis idlisen yidlisen | aberkan taberkant iberkanen tiberkanin krayellan tsednan aberqemmuc dakken asgainna ayisnnek | amellal umellal tamellalt imellalen yimellalen tmellalt mellul tmellalin timellalin mellulet | tameqqrant tameqrant ameqran ameqqran ameqṛan timeqqranin timeqranin imeqranen meqqren aḥeqqar | amecṭuḥ tamecṭuḥt mecṭuḥit mecṭuḥet imecṭuḥen tameẓyant tamurt taḥanut teɣlust anect |

| ell (Greek) | σκύλος σκύλους σκύλο σκύλου σκυλί σκυλιά δύσκολο του σου σκότωσε | γάτα γάτας γάλα γάτες γάτος είναι είσαι φοβάται κοιμάται τα | βιβλίο βιβλίου βιβλία τίτλος έβαλες βάλε το του ιστορικά ανήκει | ψωμί ψωμιού σκορδόψωμο μέρα κάνω αυτοί τομ μισό έκοψε είναι | νερό νερά νερού άερα πίνει πίνεις καλύτερο είναι έργα δεν | γάλα για υγεία σόγιας λίγο αλλεργικός | σπίτι στις πάτε πόδια είναι τεράστιου ποια παιδιά στο σπό | μέρα ημέρα μέσα μέρες ημέρες μέχρι χώρα σήμερα μια μία | τρώνε τρώει να ένα τρώω τομ τον φάω φάε τα | κοιμάμαι κοιμάται κοιμάσαι κοιμήθηκα κοιμήθηκαν κοιμήθηκε κοιμήθηκες κοιμόταν κοιμούνται κοιμηθεί | διαβάζει διαβάζεις διαβάσει διαβάσεις διαβάσω διαβάζω διάβασα διάβασμα διάβαζα διάβασε | μαύρο μαύρος μαύρα μαύρη μαύρες τομ του τον το αγοριού | άσπρο άσπρος άσπρα άσπρη άσπρους εκείνα είναι εμφανίζεται έναν ένας | μεγάλο μεγάλος μεγάλοι μεγάλα μεγάλη μεγάλε μεγάλες μέγαλος μεγαλύτερη μεγαλουπόλεις | μικρός μικρό μικρή μικρά μικρού είναι μεσαία μένα ένα ενός |

| hun (Hungarian) | kutyát kutyád kutyám kutyák kutyákat kutyámat kutyáját kutyánkat kutyája kutyánk | macskákat macskádat macska macskája macskát macskám macskád macskákért macskával macskánk | könyvet könyveit könyvét könyvei könyved könyvek könyve könyveket könyvedet könyveim | kenyeret kenyérhez kenyérre kenyérben kenyerünk bundáskenyeret kenyér kenyérből kent milyen | vizet vizem vized vízen vízben vízzel vízhez vízre vízbe vizünk | tejet tejed tejjel tehenet tejből tej teheneket vajat fejni sajt | otthon itthon otthonom hazafele hazafelé otthonukról haza házat tom tomi | nap napig napok napot napon napja napom napod napokra naponta | eszem eszel eszik eszi szeretnél szeretnék esznek eszünk vettem ettem | aludni elaludni aludnom alszik alszok aludj aludt aludjunk aludtunk aludtam | olvastad olvastam olvassam olvasni elolvasni olvasod olvasok olvasom olvasol elolvastam | fekete feketébe feketék feketében felhőket koromfekete szeretem nekem feketepiacról végezte | fehér fehérre fehérbe falfehér fehérnél fehérbor elfehéredik megfehéredett festette fordult | nagy vagy nagyon nagyok mary vagyok egy nagyvárosban nagyvárosok hogyan | kicsi kocsim kicsiben kisvárosban kisvárosból kis cicije kisbicskát szókincsed kilátást |

| hye (Armenian) | շունը։ շունը շունդ շունն շուն անունը շանը շանը։ շան։ ունի | կատուն կատուն։ կատու։ կատուս կատու կատուները կատուները։ կատուներ կատուների կատվին։ | գիրքը։ գիրքը գրքեր գրքերը գրքերն գրքեր։ գիրքն գիրք գրել գրքում։ | հաց հացը հաց։ հացն հացը։ գնեցի։ գնեց։ գնելիս։ առավ։ պատվիրեցի։ | ջուր ջուրը ջուր։ ջուրը։ մաքուր նոր ունի ջրով խմում։ ու | կաթը կաթ կաթի կաթ։ կաթը։ կատուն խմել։ խմել եմ են | տուն տուն։ տանն տա՞նն տանը տանը։ տան շուտ տանել։ յաննին | երեկ երեք ամեն մենք մերին երբեք այն տանն համար նրան։ | ուտում։ ուտու՞մ։ ուտում ուտո՞ւմ ուտու՞մ ուզում ուտել։ ուտես։ ուտելու ուտելու։ | քնում։ քնում քնել։ քնեք։ քնելը քնեց։ քնո՞ւմ քնել քնեցի քնեցի։ | կարդացել կարդացե՞լ կարդում կարդում։ կարդո՞ւմ կարդացել։ կարդալ կարդալ։ կարդա։ կարդաց | սև սա ես այս են։ եք։ ամեն ամպերով։ մեքենան նա | սպիտակ սպիտակ։ պատերը պատը տունը։ սա առյուծը է։ | մեծ մե՞ծ մեծ։ մենք ամեն է։ չէ։ են։ եմ աչքեր | փոքր փոքրիկ բնակարանը բառարանը է։ էր։ որքա՞ն մեր երկիր էր |

| ind (Indonesian) | anjing anjingku anjingmu anjingnya ingin jangan anaknya anggur siang makanan | kucing kucingku kucingmu kucingnya bukan makan temukan ikan menyukai ini | buku bukuku bukumu bukan bukunya suka baru bukubuku aku kesukaanmu | roti rotinya dari tom itu turun wanita memberikan air mentega | airnya air dari hari ada udara mandi mineral sendiri pantai | susu susunya sudah sebelum nasi sapi dua setiap dari di | rumah kerumah rumahmu rumahku rumahnya sebuah hujan bukan apakah pulang | hari sehari harimu hasil harga nasi hampir seharian harihari kemarin | makan akan makanan memakan dimakan maukah malam ikan mana kacang | tidur tertidur tidurlah tidak ribut yaitu menidurkanku badak dua itu | membaca membacakan dibaca beberapa baca dibacanya majalah sebuah bukunya padaku | hitam kita wanita minum tanpa itu melihat pakaian tikus putih | putih seputih batubatu hitam salju itu ini | besar sebesar gambar sejajar semua seluas osaka sebuah sebelum terkadang | kecil memiliki sempit lakilaki mencarikan terlalu kita tetapi tinggal ini |

| isl (Icelandic) | hundinn hundurinn hundinum hundanna hundarnir hundur kötturinn hundasýningu eigandinn hundar | kötturinn köttinn köttur hundurinn maðurinn kettir ketti kattar kettinum kött | bókina bókin bókinni bók bóka bókarinnar bækurnar bækur tekur kemur | brauð brauðbita borðarðu borðaði borða að með er | vatn vatns vatni vatnið vatninu vatnsglas kranavatn vertu flöskunni fötunni | mjólk mjólkar | heima heim heiman heimilið eins heimabæinn til mig minnir er | daginn dagurinn dagsins dag daga dagana enginn degi segir lengi | borðar borða borðað borðaði borðum borðarðu orðin borðaðirðu brauð að | sofa sofið svefni svefns sofandi sofnaði svefn svafst svaf hafa | lesa lesið þessa lestu skáldsöguna skáldsögu elska lestur enska þessar | svartir svartur svört svart svörtu svörtum kolsvart svartklædd var stór | hvítar hvíta hvítt hvít hvítur hvítklædda hvað þetta hvítvínsglas eða | stórt stór stóra stóri er ert eru stóran stórir en | lítill lítil lítið litlum litlir litla hluti með lítið bill leit |

| kan (Kannada) | ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳು ಇಲ್ಲಿವೆ ಇಲ್ಲಿಗೆ ಮಾತ್ರವಲ್ಲದೆ ಮಾತ್ರವಲ್ಲದೇ ಇಲ್ಲಿ ಇಲ್ಲಿನ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳಾದ ಕತ್ತೆ | ಚಿರತೆಗಳು ಚಿರತೆಗಳ ಕಾಡು ಕಂಡು ಬೆಕ್ಕು ಬೆಕ್ಕಿನ ಶ್ರೇಣಿಗಳನ್ನು ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳನ್ನು ಕಾಣಬಹುದು ಕಾಣಬಹದು | ಪುಸ್ತಕಗಳು ಪುಸ್ತಕಗಳ ಪುಸ್ತಕಗಳನ್ನು ಪುಸ್ತಕವನ್ನು ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರು ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರಿಗೆ ಮತ್ತು ವಸ್ತು ಎತ್ತರ ಪುಸ್ತಕಗಳಿವೆ | ಹಾಗು ಪ್ರಶಾಂತ | ಮತ್ತು ಮುತ್ತು ಮತ್ತೆ ಹೊತ್ತು ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರ ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರು ಮತ್ತೊಂದು ಮರೆತು ಸುತ್ತಲು ನೀರಿನ | ಮಾಡಿಸಲಾಗುತ್ತದೆ ಮಾಡಲಾಗುತ್ತದೆ ನೀಡಲಾಗುತ್ತದೆ ನಂಬಲಾಗುತ್ತದೆ ಪೂಜಿಸಲಾಗುತ್ತದೆ ಹಾಲನ್ನು ಹೆಸರನ್ನು ಮತ್ತು ಭಕ್ತರು ಮಾತ್ರ | ಅಳಿವನಂಚಿನಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಅಳಿವಿನಂಚಿನಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಮತ್ತು ಮುತ್ತ ಪಕ್ಷಿಗಳಿವೆ ಪಕ್ಷಿಗಳಿಗೆ ಕತ್ತೆ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳು ಮನೆಯಾಗಿದೆ | ದಿನಗಳಲ್ಲೂ ದಿನಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಬೆಳಗ್ಗೆ ಬೆಳಿಗ್ಗೆ ಆಚರಿಸಲಾಗುತ್ತದೆ ನೆರವೇರಿಸಲಾಗುತ್ತದೆ ತೆರೆದಿರುತ್ತಿದ್ದು ತೆರೆದಿರುತ್ತದೆ ಮತ್ತು ಮತ್ತೆ | ಸೇವಿಸುತ್ತಾರೆ ಸಲ್ಲಿಸುತ್ತಾರೆ ಆಹಾರಗಳನ್ನು ಆಹಾರವನ್ನು ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರಿಗೆ ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರೂ ಕೊಲ್ಲುತ್ತಾರೆ ಮಾಡಬಹುದು ಮಾಡುವುದು ತಿನ್ನುತ್ತಾರೆ | ಇಲ್ಲಿ ರಲ್ಲಿ ಇಲ್ಲಿಗೆ ಮಲಗಿರುವ ಮಲಗಿರುವಂತಹ ಒದಗಿಸುತ್ತದೆ ತೋರಿಸುತ್ತದೆ ಮಲಗುವ ಎಲ್ಲಾ ಎಲ್ಲರ | ಸೂರ್ಯಾಸ್ತಮಾನವನ್ನು ಸೂರ್ಯಸ್ನಾನವನ್ನು ಇಲ್ಲಿನ ಇಲ್ಲಿಯ ಇಲ್ಲಿ ಸ್ವಾಗತವನ್ನು ಕ್ರಾಂತಿಯನ್ನೇ ನಲ್ಲಿ ಶಾಸನವೊಂದನ್ನು ಹೆಸರುಗಳನ್ನು | ಕಪ್ಪು ಕೆಂಪು ಕಟ್ಟು ಕಪ್ಪುಕರಡಿ ಇಲ್ಲಿ ಇಲ್ಲಿನ ಮತ್ತು ಮತ್ತೊಂದು ರಫ್ತು ಬೆಕ್ಕು | ಬಿಳಿ ಬಿಳಿಯ ನಿರ್ಮಿಸಲಾಗಿದೆ ನಿರ್ಮಿಸಲಾಗಿರುವ ಮತ್ತು ಮತ್ತೊಂದು ವಸ್ತು ನಿರ್ಮಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿದೆ ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರು ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರನ್ನು | ದೊಡ್ಡ ದೊಡ್ದ ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರ ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರು ಇಲ್ಲಿ ಇಲ್ಲಿನ ಇಲ್ಲಿದೆ ಇಲ್ಲಿಗೆ ನಲ್ಲಿ ದೊಡ್ಡದಾದ | ಸ್ಥಳದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಸಮೀಪದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಇಲ್ಲಿವೆ ಇಲ್ಲಿಗೆ ಅಲೀಗಢದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ದೂರದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಪ್ರವಾಸಿಗರು ಪ್ರವಾಸಿ ರಸ್ತೆಯಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಜಿಲ್ಲೆಯಲ್ಲಿರುವ |

| kat (Georgian) | ძაღლია ძაღლი ძაღლის ძაღლს ძაღლები ძალიან ძაღლთან აი არ | კატა კატები არის | წიგნი წიგნის წიგნია წიგნში წიგნს წიგნებია წიგნები წიგნების წიგნმა ისინი | პური პურს ვჭამ ჭამს მაქვს ვიყიდე | წყალს წყალი წყლის | რძე რძეს რძისგან სახლისკენ მე | სახლში სახლშია სახლი სახლიდან სახლისკენ ახლა ლეილას დარჩით ისინი დაბნელებამდე | დღე დღეს დღეა დღეში დღის ყოველდღე რამდენ მე ბარდება ეს | ჭამს ჭამას ვჭამ ვჭამთ ჭამა გიჭამია გვიჭამია მიირთვა მიირთვი დესერტი | მძინავს სძინავს გძინავს დაეძინა დაიძინა ძინავთ გვეძინა ეძინათ მეძინა დასაძინებლად | კითხულობენ კითხულობს ვკითხულობ წაიკითხა წავიკითხავ კითხვა | ძაღლი შავია | არის თეთრი | დიდი სახლი ის | პატარა მდინარის მახლობლად სახლში ტომი |

| lit (Lithuanian) | šunis šunys šuns šunį šunų šunims šuo šuniui nusipirkau nusipirkti | katės katė katę kates katinai katinas katei kėdės katiną kam | knygą knyga knygų knygas knygos knygoje mokiniai naudinga laikai yra | duoną duona duonos duok parduoda kurią nori nuo pikto žinau | vandens vandenį vandeniu vanduo vienas sunkesnis sūresnis daviau kareiviai negalėtume | pieno pieną pienu pienas geria geriu neduoda išgerti nori palaukti | namo namų namie namai mano esame neeiname neturite mane taip | dienų dieną diena dienas viena dienos dienoms dienom dirba kasdien | valgyti valgti pavalgyti valgėte valgei valgom valgo suvaglyti nevalgo nevalgė | miegoti pamiegoti miegojai miegojo miega miego miegu miegi miegojau miegantį | skaityti perskaityti skaitai skaityk perskaitysi perskatyti skaitoma neskaityk skaitau perskaitysiu | juodas juoda juodai juodų juodo juodą juodus juodos juokiasi lova | balta baltas baltą balto matau pabalo | didelis didelias didelių dideli didelė didelį viena | mažas mažos maža mažame matai namas maži mažą mažoje labai |

| lvs (Latvian) | suni suns sunim suņi mans suņu mani manu suņiem sāka | kaķis kaķus kaķim kaķi kaķa mazākais raibais tikai kaklu vairāk | grāmata grāmatu grāmatas grāmatām smaga man tava ir tā | maizi maizes rupjmaizi kvass esi kas ar ir | ūdens ūdeni ūdenī ūdenim ūdenstilpē minerālūdens iedevu gruntsūdeņus putni nedzeru | pienu piena piens rūgušpienu priekšroku reta nedzer pazīstama un ir | mājās mājām atstājis atstāja nerunājam aizmirsa sekoja savu angliski ej | dienu diena dienā vienu dienas dienai ēdiena dienās viena dienām | ēstu ēst ēd ēdu mēs ēdīs ēdīsi ēdis neēdu ēdīšu | gulēju gulēšu gulēja gulēji gulēt pagulēt gulēsi guļot guļ guļu | lasīt lasītu lasot grāmatas grāmata lasīja lasīju izlasītu lasījis lasu | melns melnas melnos melnās melna melnā melnu melnai melnie melnajā | balts baltu baltā balto baltais bars melnas bikses tas straumi | liela lielu lieli lielā liels lielās lielām saule saules tai | mazas maza mazu mazs mazā mana manam maziem marija redzama |

| mkd (Macedonian) | кучето кучево кучиња кучињата куче кучка куки кое очекуваше чуваше | мачкава мачката мачките мачка мачки сака сакам кучиња имам таа | книгата книгава книги книга книгите читаш дека магии премногу на | леб леп лебот треба ли е со во од на | водата водава вода додај додека воденица навадам доволна создаде да | млеко млекото млеково мене козјо пиеме смееме колку ако може | дома дом мама додека том има домашните одам одиме да | ден дена еден денес денов денот дедо арен две дневно | јадам јадат јадеш јаде јадел јадеме јадеше јади јадење јадено | спијат спијам спие спиев спиеш спиел спиеле спиење спиеше спиј | прочитам прочита прочиташ прочитал прочитав читам чита читаш читал читаше | црни црно црна црн црниот том тоа црнец црната црнокос | црнобели црнобело бели белци бела бело бел белата белиот врело | голема големо големи голем том тоа поента помогна главното главната | мала мали мало мал малата табла премала премали премало малечка |

| nob (Norwegian Bokmal) | hunden hundene hunder under hund hun rundt nesten sovende hans | katten kattene katter katt klatre hater etter svarte kanskje elsker | bøker bøger bøkene boken bokas boka bok noen ønsker denne | brød brødet dere denne drar ludder allerede de er egentlig | vann vanne vannet mannen vanndamp enn var renne varer plantene | melk melken melkekyr melkeallergi melkeproduksjon drikker i | hjem hjemme jeg hele komme kommer hvis rette der deg | dagen dager dag deg ganger klager dagboken leger lang gang | spiser spise spiste spises spist spis pisa disse spisesalen pizza | sovet sover sove sovende hver sov ideer søvn ligger som | lese leser leste lest eller hele eventyr allerede denne disse | svart svarte sort var hvit hatt har katten hesten en | hvit hvite hvitt har var hest katten kanter svart vi | stort stor store svart som etter sett et er en | liten lite litt lille gutten den en enn kvinnen enden |

| ron (Romanian) | câinele câinelui câine câini caine câinilor cine câinii inventat nevoie | pisica pisică pisici pisicii pisicile pipăit scăpat trecea petrece mănâncă | carte cartea aceasta această care cărți cărții cărui foarte cărțile | pâinea pâine taie pe proaspătă în ai | apă apa apei apus proaspăt piatră puțină luxoasă pe era | laptele lapte poate alerga turnat ea el a | acasă casă casa școală astăzi șase acum tatăl meargă rămas | zi azi duminică duminica zile zilele săptămâna săptămânii ai fi | mănânci mănânc mănânce mănâncă mănâncăți mânca mâncat mâncați mâncăm mâncare | doarme doarmă dormi dormit dormind dormea dorm adorm dormeau dormeam | citit citite citito citești citește citim citesc citească citi cartea | negru negrul negre negri neagră afară mereu fiecare erau grup | alb albă albe albi ale sau astăzi lebedele umple ca | mare mari are marile țară tale foarte mărire favoare gaura | mică mici mic este ești asta există acesta acest camera |