Suppose you have a picture frame with a loop of string attached to the back and you need to hang it on the wall. If there are two nails stuck in the wall, how can you tangle the string around the nails so that removing either of the nails will cause the picture to fall down?

If you have $n$ nails in the wall, can you come up with a way to hang the picture so that removing any one of the nails causes it to fall?

Give that first puzzle a try before moving on. It‘s tricky, but you should be able to figure it out after playing with a piece of string for a few minutes. The generalization, however, is much trickier and is more easily solved using math than with an actual piece of string. These problems will introduce us to an interesting mathematical concept that we‘ll explore more abstractly for the rest of the post.

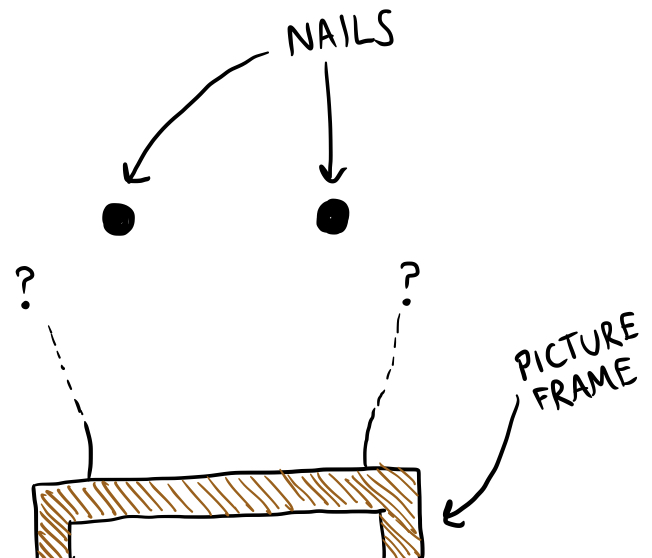

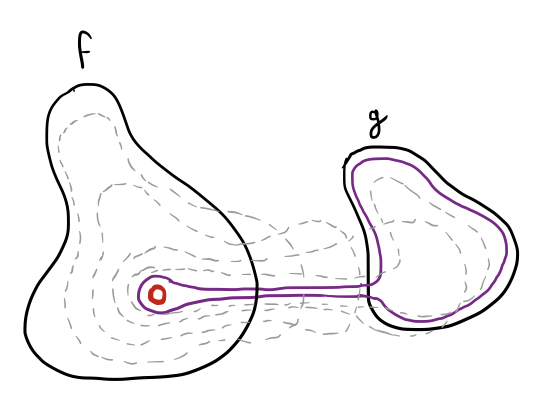

So let‘s start by methodically solving the first problem. We have two nails in a wall (which are depicted as points in the picture below, as if we were looking at them head-on) and a loop of string that we need to pass over the nails in some way. We don‘t know exactly how we‘re going to do this yet, so I‘ve just drawn the string vanishing into space:

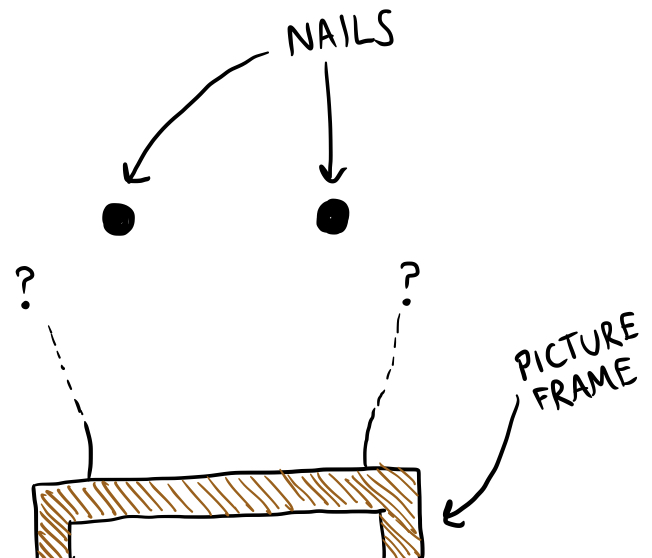

This seems hard, since there are potentially an infinite number of things that we could do with this string. But lots of these things are actually the same thing. These three loops are all essentially the same:

All of those fancy loop-de-loops don‘t actually affect how the string is looped over the nails. We might say that they are equivalent to each other because they can be continuously deformed into each other without pulling the string off of the nails at any time.

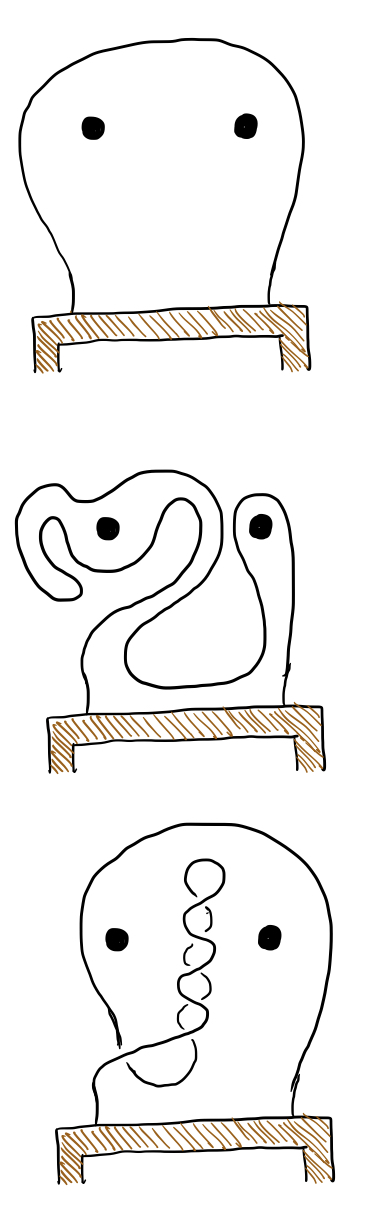

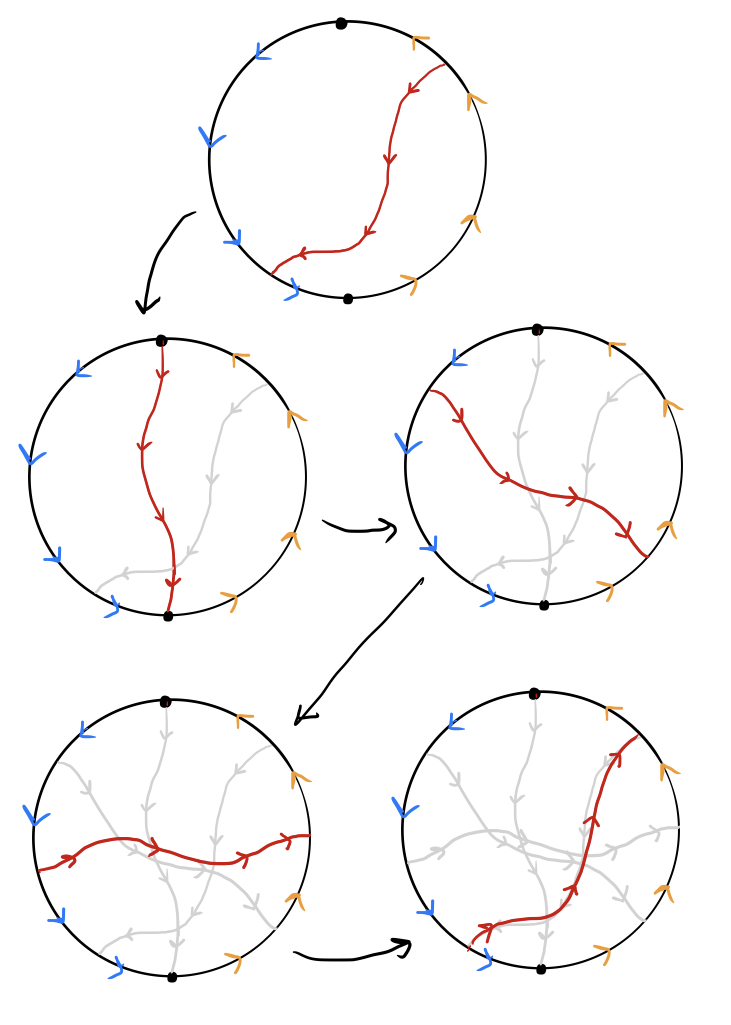

If we don‘t care about the exact shape the string makes and only care about how it is passed over the nails, there are far fewer possibilities to consider, and all of them can be obtained using some combination of the following “moves”:

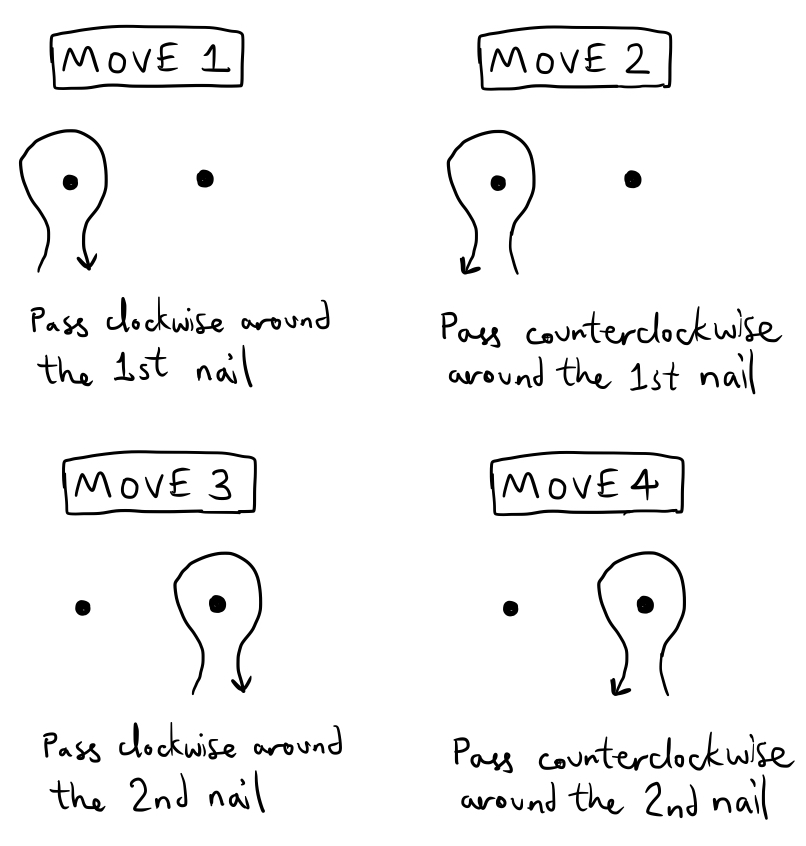

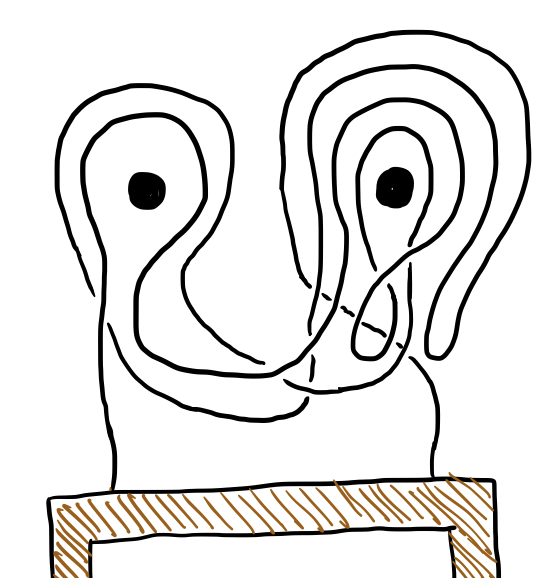

By doing some complex sequence of moves, we can get some kind of weird tangle around the nails. For example, if we do $133234$, we get something like this:

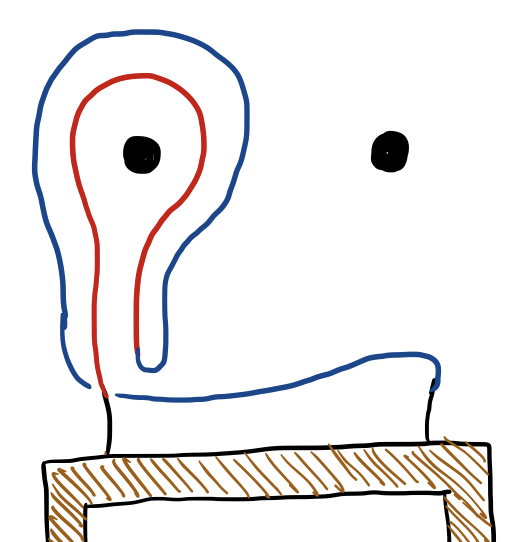

Notice that if we do move $1$ immediately followed by move $2$, they “undo” each other and the string doesn’t end up looped around the first nail at all:

The same is true if we do move $2$ and then move $1$, and this also occurs with move $3$ and move $4$. We might say that move $1$ and move $2$ are inverses, and move $3$ and move $4$ are also inverses. Now it’s time to introduce some notation. Let’s use the symbol $a$ to stand for move $1$, the symbol $a^{-1}$ (“a inverse”) to stand for move $2$, $b$ for move $3$, and $b^{-1}$ for move $4$. To describe a long sequence of moves, we can list these moves from right to left in a string, so that the strange tangle we came up with earlier would correspond to the string $b^{-1}ba^{-1}bba$. It may seem strange to list these from right to left instead of left to right, but I’ll explain later why I’m doing this.

As we noted before, $a$ and $a^{-1}$ “undo” each other, as do $b$ and $b^{-1}$, so if we are considering a string in which $a$ is adjacent to $a^{-1}$ or $b$ is adjacent to $b^{-1}$, we can cancel the two. For instance, the loop represented by $b^{-1}ba^{-1}bba$ would be equivalent to that represented by $a^{-1}bba$.

Now let’s apply this notation to our original problem: to find a loop that completely unravels when either nail is removed. If we pull one of the nails out of the wall, every loop around that nail essentially “vanishes,” like all of the extravagant but essentially equivalent loop-de-loops that I drew earlier. In the context of our “loop language,” if we pull out the first nail, all of the instances of $a$ and $a^{-1}$ should disappear from our string, and if we pull out the second nail, all instances of $b$ and $b^{-1}$ should disappear. For instance, the loop $a^{-1}bba$ would turn into $bb$ when the first nail is removed, but when the second nail is removed, it would turn into $a^{-1}a=e$, where $e$ represents a trivial, unlooped loop.

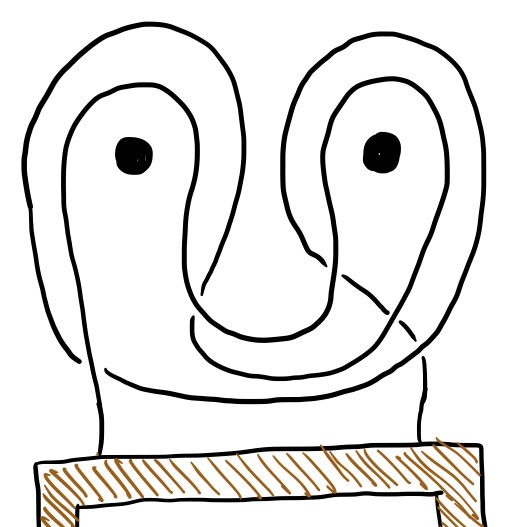

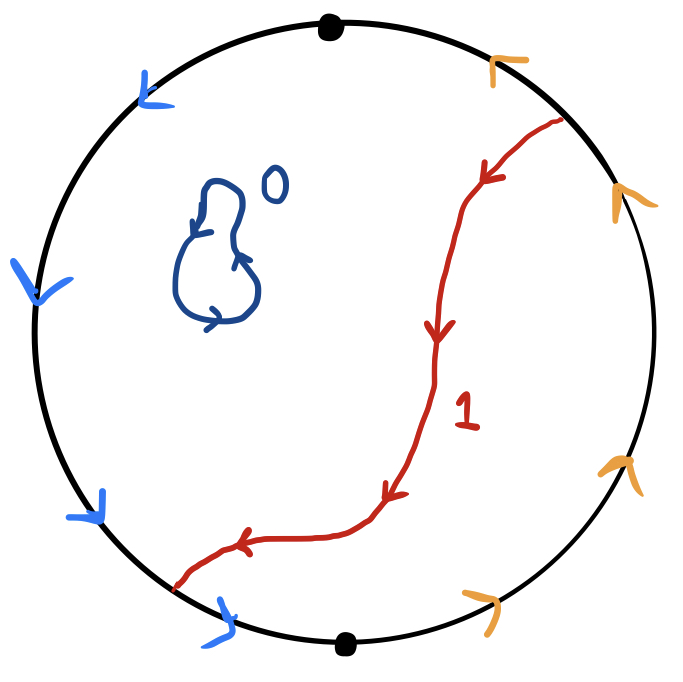

So if we want to find a loop that unravels when we pull either nail out, what we need is a string of $a,a^{-1},b,b^{-1}$ that reduces down to $e$ when all of the $a,a^{-1}$ are removed or when all of the $b,b^{-1}$ are removed. It’s not hard to find such a string - the simplest example is $b^{-1}a^{-1}ba$, which stands for the following loop:

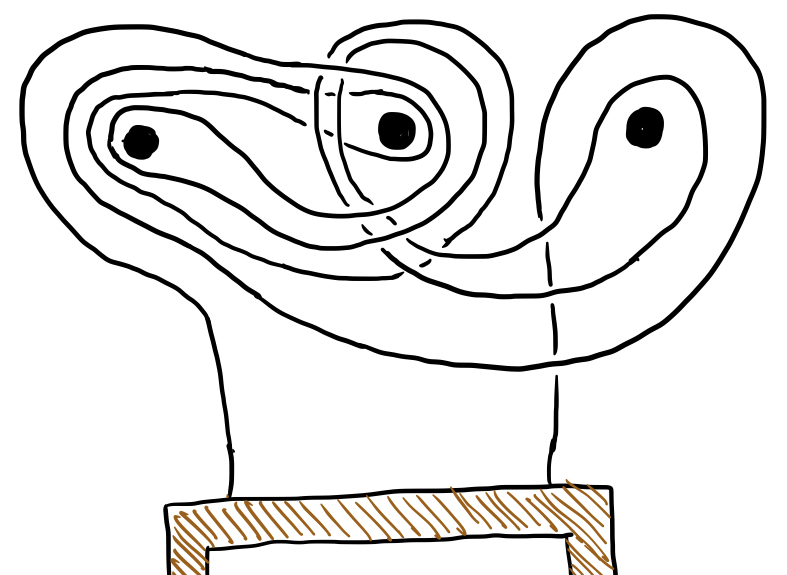

If you try visualizing that picture without either of the nails, it should be pretty easy to see how the string is no longer hooked on the other nail. The problem with more than $2$ nails gets much trickier, but is is much harder to figure out with an actual string than with the symbolic language we’ve been using. When we have $3$ nails, there are $6$ basic moves, which we can denote $a,b,c,a^{-1},b^{-1},c^{-1}$. A possible solution for the 3-nail problem is given by $c^{-1}a^{-1}b^{-1}abcb^{-1}a^{-1}ba$, which requires a lot more string:

But we can verify that this does indeed fall apart when any of the nails is removed by using the string of characters. Notice that or we might even write So we can write the 3-nail solution as or, if we make a substitution $\beta=b^{-1}a^{-1}ba$, We know that if we remove either $a$ or $b$ (and their corresponding inverses), then $\beta$ and $\beta^{-1}$ will be eliminated, leaving just $c^{-1}c=e$. If $c$ and $c^{-1}$ are eliminated (corresponding to the third nail being removed), the string reduces to $\beta^{-1}\beta=e$.

We can use this same little trick to construct a solution for the 4-nail problem. If we let $d$ represent a clockwise loop around the fourth nail and let $\gamma$ represent our solution to the 3-nail problem (in terms of $a,b,c,$ and their inverses), then will be a solution to the 4-nail problem. Deleting $a,b,$ or $c$ causes $\gamma$ to vanish, allowing $d^{-1}$ and $d$ to cancel each other; deleting $d$ alllows $\gamma^{-1}$ and $\gamma$ to cancel. If we expand the above solution by replacing $\gamma$ with the corresponding expression in $a,b,c$ that it represents, we obtain the following string of length $22$: If we continue using this recursive technique to construct solutions for the 5-nail problem, the 6-nail problem, and more generally the n-nail problem, we will obtain strings of length $46$, $94$, and, in general, $2^n+2^{n-1}-2$. However, using a more efficient construction technique, it is possible to build solution strings to the n-nail problem with length less than $\frac{3}{2}n^2-n$ for all $n\ge 2$. But I’ll leave that as an exercise for any sufficiently interested reader.

In case you haven’t noticed already, this cute mathematical language we’ve been using is called a group. In general, a group $G$ is defined as a set with a single operation (that must satisfy a few important properties, which we’ll go over in a second). If $a,b$ are two elements of $G$, their “product” (or “sum,” or whatever you want to call G’s operation) is written as $ba$ or $ab$. However, it is not necessarily the case that $ab=ba$ - the operation is not necessarily commutative. Here are the properties that a group operation is required to satisfy:

There are lots of examples of groups. The integers $\mathbb Z$ with the operation of addition form an infinite group, and for that matter the reals $\mathbb R$ with the operation of addition would also form a group. The identity element of these groups would be $0$, and the inverse of the element $x$ would be $-x$. Another very simple example of a group is $\mathbb Z_2$, which is the set ${0,1}$ with an operation called $+$ defined by $0+0=0$, $0+1=1$, $1+0=1$, and $1+1=0$. The set of invertible $n\times n$ square matrices under multiplication forms a group, and so does the set of bijective functions $f:[0,1]\mapsto [0,1]$ under the operation of function composition.

The group that we were playing with earlier in the 2-nail problem was something called the free group with two generators, denoted $F_2$. This is basically the set of all strings of characters $a,b,a^{-1},b^{-1}$ under the operation of concatenation, with the additional property that the characters $a$ and $a^{-1}$ cancel each other, as do $b$ and $b^{-1}$. The identity element $e$ would be the “empty string,” or a string containing no characters. The inverse of a long string of characters could be obtained by listing the inverses of its elements in reverse order, like this: For convenience, from here on out, whenever we write a long string of the same character like $aaaa$, we will write it more compactly using exponent notation, so that $aaaa$ would be denoted $a^4$. Using this notation, the above example would be written We can also have a free group with $3$ generators, using $a,b,c$ and their inverses instead of just $a,b$. For that matter, we can even have a free group with $n$ generators, which is denoted $F_n$.

We can also define more complicated spin-offs of the free groups by adding additional relationships between their generators. For instance, suppose we wanted to consider a modified version of $F_2$ in which $a$ was equal to its own inverse, so that $a=a^{-1}$ or $a^2=e$. We would define such a group using the following notation:

or, even more concisely:

This group would have elements like $ab^3abab^{-4}$ or $b^{-1}ab^{-2}$ consisting of “powers” of $b$ separated by single characters of $a$. This is because any repetition of more than one $a$, like $a^5$, could be reduced to either $e$ or $a$ using the rule $a^2=e$. For instance, $a^5=a^2a^2a=eea=a$. We can get even more complicated and define strange groups like which would be a group in which $a^5=e$ and $b^7=e$, or in which $a^2b^2c^2=e$.

There are also lots of ways to make new groups out of old groups. For instance, if we have two groups $G,H$, we can define their direct product $G\times H$ as the group whose elements are all of the ordered pairs in the form $(g,h)$ where $g\in G$ and $h\in H$, and define the operation in $G\times H$ as where $g_1g_2\in G$ and $h_1h_2\in G$. Let’s look at a few examples. Consider the group $\mathbb Z\times\mathbb Z$, or $\mathbb Z^2$. This would be the set of all two-dimensional integer vectors under vectors addition, so that, for example, Or we could even consider $\mathbb Z\times\mathbb Z\times\mathbb Z$, or $\mathbb Z^3$, which is the set of three-dimensional integer vectors. In $\mathbb Z^3$ we would have You could also define $\mathbb Z\times\mathbb Z_2$, in which Or even the crazy group $\mathbb Z\times F_2$, in which we have an operation that does things like this:

There’s also another way to combine two groups called the free product. If $G,H$ are groups, then we can form their free product $G*H$ by essentially letting their elements “intermingle” with each other to form long strings like in the free groups $F_n$. For instance, the free product of $\mathbb Z_2$ with $F_2$ would have elements like and “products” like the following would be possible: Notice that the identity elements of the two groups ($e$ and $0$) are taken to be identical so that, for instance, $a11a^{-1}=a0a^{-1}=aea^{-1}=aa^{-1}=e$. As another example, it’s pretty easy to see that if $F_m$ and $F_n$ are two free groups, then $F_m * F_n=F_{m+n}$.

But what does any of this stuff have to do with the problems we considered earlier? After all, this blog post is called “Groops and Loops.” We’ve talked about groops, but what about the loops?

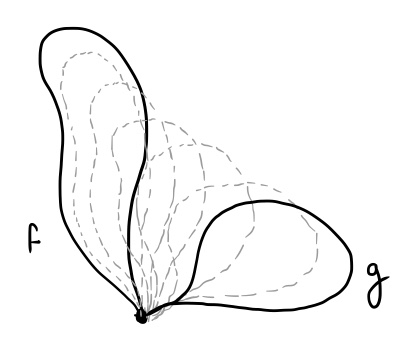

Let’s start by giving a formal definition of what exactly we mean by a “loop.” Given a topological space $S$, we can define a loop as a continuous function $f:[0,1]\mapsto S$ with the property that $f(0)=f(1)$. As mentioned earlier, lots of these loops are often “equivalent” in the sense that one can be continuously deformed into the other, a statement that also warrants a rigorous mathematical definition. If we have two loops defined by the functions $f$ and $g$, then we say that they are equivalent if there exists a continuous homotopy $H:[0,1]^2\mapsto S$ such that $H(x,0)=f(x)$ and $H(x,1)=g(x)$ for all $x\in [0,1]$. The function $H$ can be thought of as “deforming” the loop represented by $f$ into the loop represented by $g$, like this:

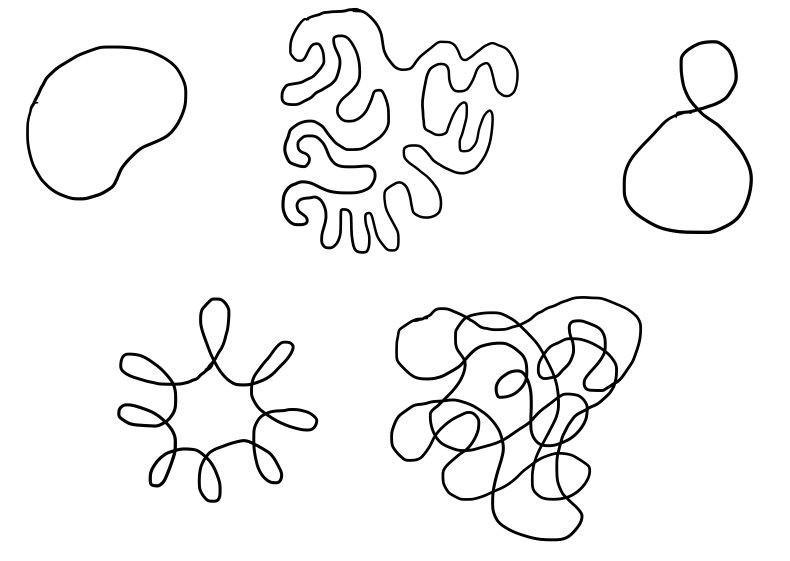

Notice that the “loops” defined by these functions are allowed to cross themselves, and the homotopy $H$ that deforms them also allows them to pass through themselves. In this way, these formalized “loops” are unlike actual pieces of string in three dimensions, which can be tied into knots that can’t be undone without cutting the string. For instance, each of the following loops would be equivalent to each other:

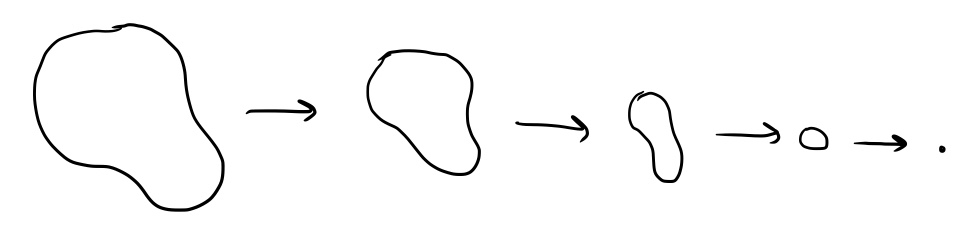

In fact, all of these loops are trivial, meaning that they can all be contracted down to a single point, like this:

In any path-connected topological space, all trivial loops are equivalent to each other.

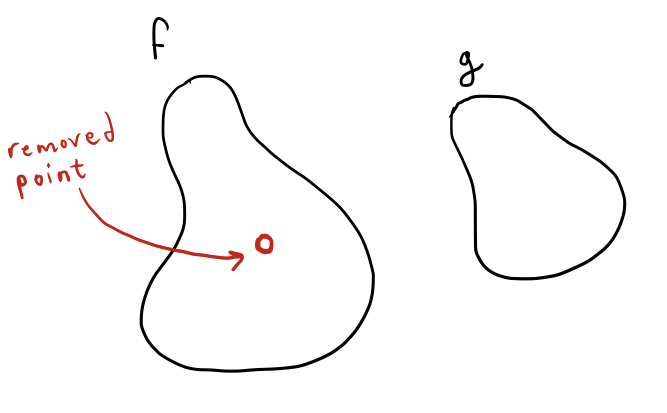

The topological space $S$ in which these loops exist need not be simply a plane $\mathbb R^2$ or 3-space $\mathbb R^3$. We could consider, for example, the plane minus a single point. In $\mathbb R^2$, all loops are trivial, but in $\mathbb R^2$ minus a point, something different happens. If a loop encloses the hole left by removing a point, it is no longer trivial, and is also not equivalent to any other trivial loop.

Try as we might, we cannot deform loop $f$ into loop $g$, because loop $f$ encloses that one pesky hole that prevents us from completing the deformation. We can get very close:

It’s almost like a piece of string getting hung up on a nail. Look familiar?

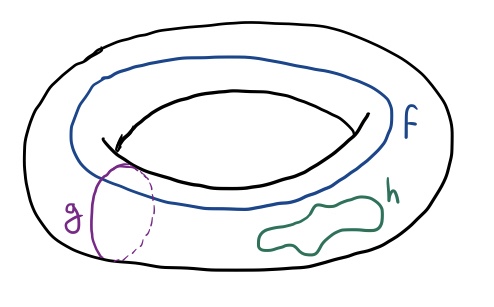

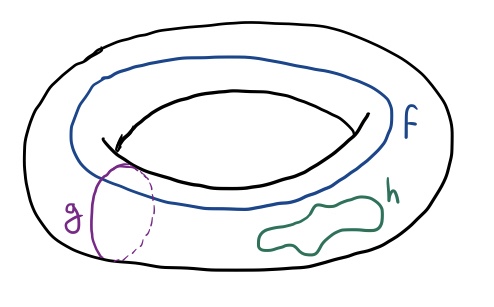

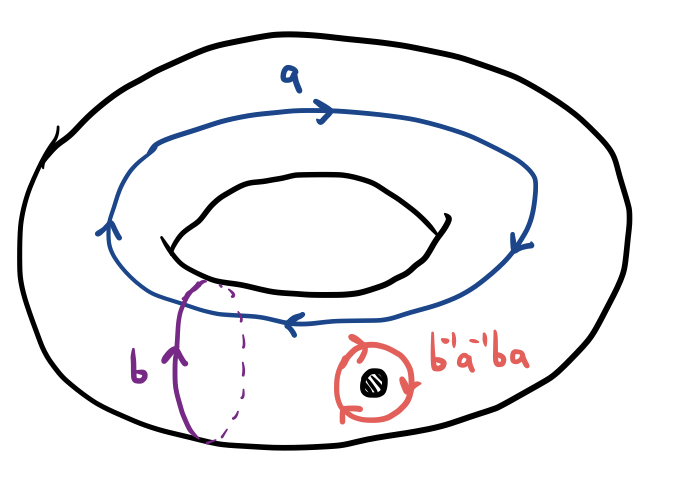

Let’s consider a more interesting example and use a torus (a surface in three dimensions that looks like the outside of a donut) as our topological space. Here’s a picture of a torus with three different loops drawn on its surface:

Only $h$ is a trivial loop, and all three of these loops happen to be mutually non-equivalent - none of them can be continuously deformed into any other.

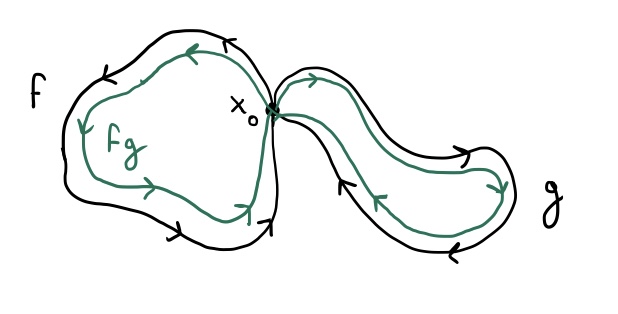

If we have two loops defined by the functions $f$ and $g$ that both start and end at the same point $x_0$, we can “combine” $f$ and $g$ to define a new loop in the following way: define $fg:[0,1]\mapsto S$ to be the function It’s easy to see that this function is continuous, since $f(1)=g(0)=x_0$ and $f,g$ are continuous. This function also defines a loop, which basically starts at the point $x_0$, goes through the path defined by $g$, then goes through the path define by $f$, ending up back where it started at $x_0$. Here’s a visual example:

Notice that in the picture above I drew arrows on the loops indicating direction. That’s because these functions don’t just define loops, but also define an orientation on the loop, like the direction in which the loop “flows.” Orientation is important! If we return to our earlier example of a plane with a point deleted, the clockwise-oriented and counterclockwise-oriented loops about that point are not equivalent to each other.

Now for the punch line - if we consider the set of oriented loops in a topological space that start and end at a single point $x_0$, and the previously described operation with which they can be combined, the resulting structure is actually a group! I’ve already explained why it is closed under the operation we’ve defined, and how “combining” two loops in this way results in another loop. It is also associative, despite the fact that the function defined by $(fg)h$ is not the same as the function defined by $f(gh)$ (because the speed at which the function parametrizes the loop doesn’t matter). It has an identity element, which is just the constant function $e(x)=x_0$, which is also equivalent to the functions parametrizing any trivial loops. Finally, it has inverses: if $f$ is a function defining a loop, then the function $f^{-1}(x)=f(1-x)$, defining the same loop with the opposite orientation, is its inverse, so that $ff^{-1}=f^{-1}f=e$.

If $S$ is some topological space and $x_0$ is a point therein, then $\pi_1(S,x_0)$ denotes the group of loops whose parametrizations start and end at $x_0$, using the “loop concatenation” operation defined earlier. Unfortunately, this is not called the “loop groop” of $S$, but rather the fundamental group through the base point $x_0$. If $S$ is a path connected space, the fundamental group will be the same regardless of the base point, in which case it is simply denoted $\pi_1(S)$. From here on, we’ll only be dealing with path-connected spaces, so I’ll stick to this notation.

In the plane $\mathbb R^2$, all loops are trivial, since they can’t get “hung up” on anything and can all be contracted to a single point. Thus, we can write where ${e}$ represents the trivial group. As you might have noticed, the n-nail problem that we considered earlier was related to the fundamental group of $\mathbb R^2$ with $n$ points removed, which is equivalent to $F_n$. So we can write Let’s consider some simpler examples before we move on to more interesting ones. Suppose that we use the circumference of a circle (denoted $S^1$) as our topological space. The fundamental group of this space is given by because every loop around the boundary of a circle can be characterized by how many times it has wound clockwise around the circle before returning to its starting point, with counterclockwise loops corresponding to the negative integers. Note that any loop that winds around $n$ times clockwise and then $n$ times counterclockwise back to its starting point is simply trivial, which corresponds to the fact that $n+(-n)=0$. Here’s a quick proof of that fact. If we take $S^1$ to be the unit circle in the complex plane (given by ${e^{it}|t\in\mathbb R}$), then a loop wrapping $n$ times clockwise and then $n$ times counterclockwise can be parametrized by the function

Now we can easily find a homotopy $H$ that deforms $f$ into a point by continuously shrinking the loop:

Clearly, from the above definition, $H(x,0)=f(x)$ and $H(x,1)$ is a constant function mapping to the point $z=1$ on the unit circle. Since $H$ is also continuous, we can see that $f$ is trivial.

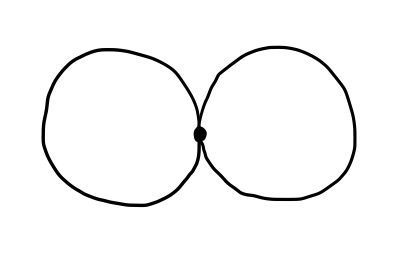

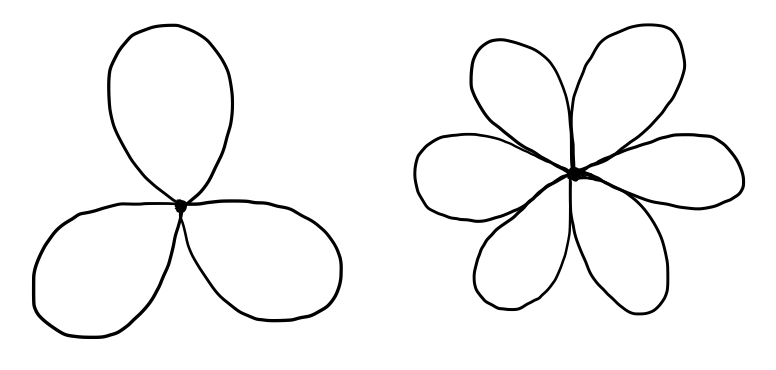

Now consider the space given by two circles joined at a point, also called a bouquet of two circles, or the wedge sum of two circles, written $S^1\lor S^1$:

In this case, a loop can wind around either circle, and a loop around one circle is not equivalent to a loop around the other circle. Thus, we’ve found another space whose fundamental group is the free group with 2 generators, or $F_2$: We can also consider a bouquet formed by $3$ or more circles, or the wedge sum of $n$ circles:

By similar reasoning to the above, we can see that the fundamental group of this space is equal to $F_n$ when we have $n$ circles. You might object that in the above pictures, I haven’t exactly drawn circles joined in a point, but teardrop-shapes. But remember that we’re dealing with topology, and that spaces that can be continuously deformed into each other are topologically equivalent, or homeomorphic. The fundamental group of a topological space is not a geometric property, but rather a topological one - any two spaces that are topologically equivalent must have the same fundamental group, so it doesn’t matter if I squish my circles a little bit to facilitate drawing.

It turns out that if $X$ and $Y$ are two reasonably “well-behaved” topological spaces (for our purposes, we’ll just say path-connected), then the fundamental group of their wedge product $X\lor Y$, the space formed by joining them at a single point, is given by the free product of their respective fundamental groups. That is,

Now let’s consider something a bit more interesting. Remember the torus (which is denoted $T^2$) that we looked at earlier?

As we can see in this picture, we have two distinct nontrivial loops on the torus, one of which (denoted $f$) circles around the hole in the torus, and the other of which circles around its body (denoted $g$). So perhaps the fundamental group is $F_2$ again?

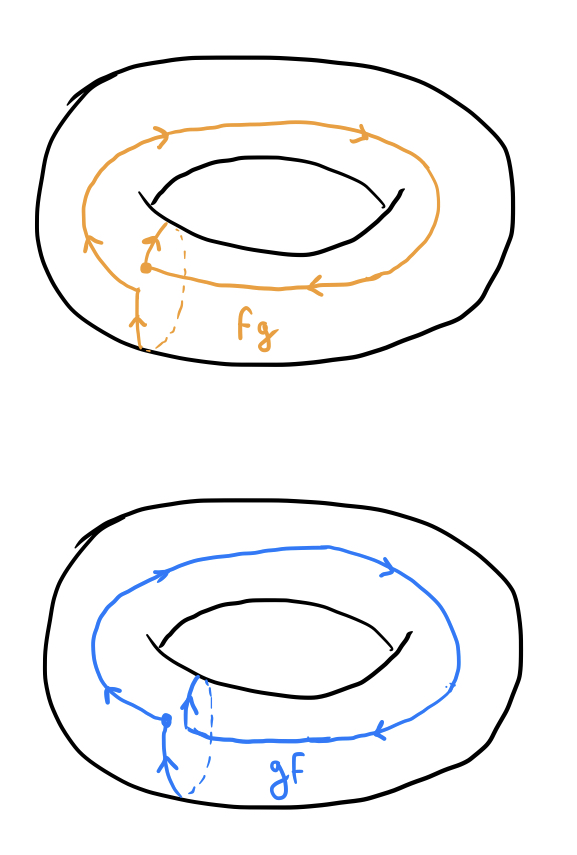

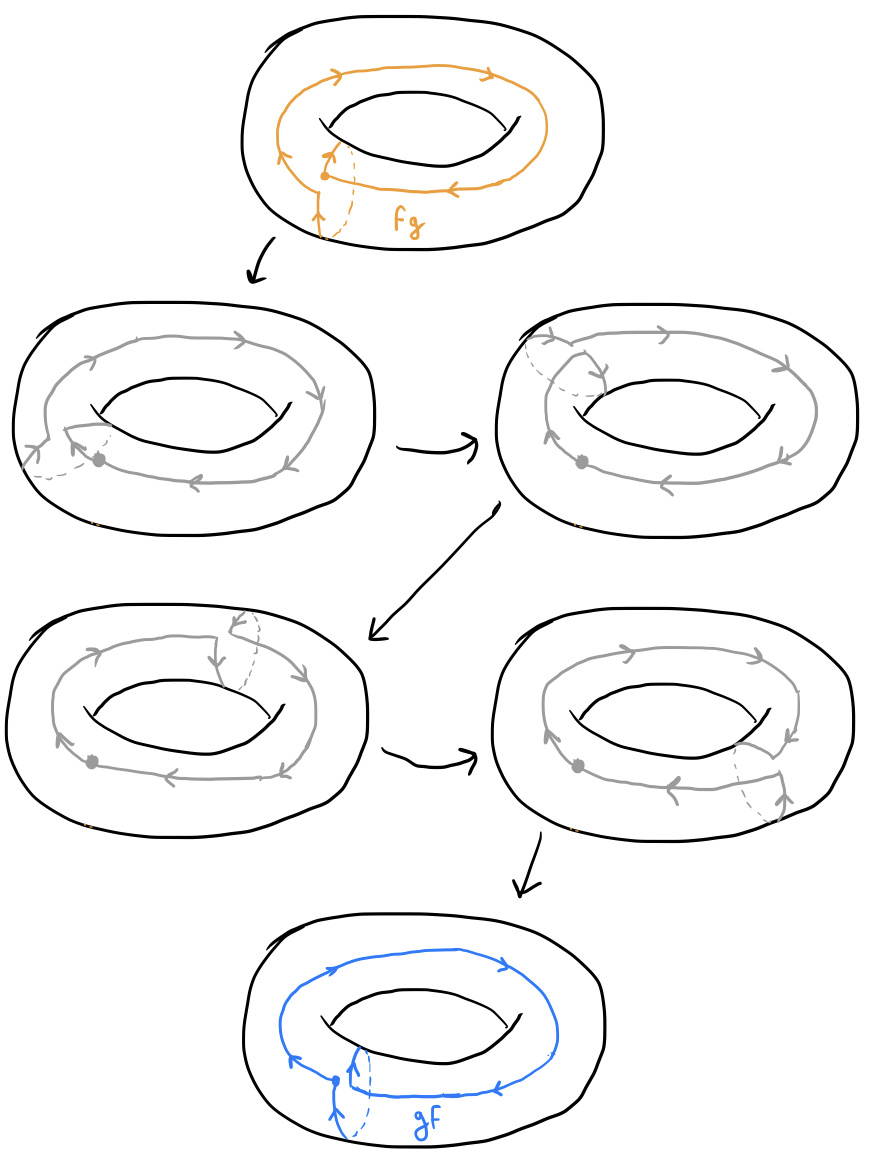

Not so! There’s something special about the fundamental group of the torus that distinguishes it from $F_2$. Let both $f$ and $g$ run clockwise, and consider the loops defined by $fg$ and $gf$:

If you visualize the circle $g$ at the beginning of $fg$ moving clockwise around the torus, you should be able to see that $fg$ can be continuously deformed into $gf$, and the two are in fact equivalent. Let’s construct a quick algebraic demonstration of this fact. Because $T^2$ is topologically equivalent to the cartesian product of two circles $S^1\times S^1$, we can represent each point on the torus algebraically as an ordered pair $(\alpha,\beta)$ where $\alpha,\beta\in S^1$ are both elements of the unit circle, with $\alpha$ indicating the position of the point around the “donut hole” and $\beta$ indicating its position around the actual body of the torus, so that all points on the loop $f$ have the same value of $\beta$ and all points of the loop $g$ have the same value of $\alpha$. We can write

and

Then we can write $fg$ and $gf$ as

Finally, we can use the following homotopy to map $fg$ to $gf$:

If all of that looked like gobbledygook, we can be a little bit less rigorous and demonstrate that $fg=gf$ by visually demonstrating that they can be “morphed” into each other continuously like this:

Since we know that $fg=gf$, we have that the fundamental group of $T^2$ is given by

and it turns out that this group is simply equivalent to $\mathbb Z^2$. Thus, we have

The fact that $T^2\cong S^1\times S^1$ makes this problem have a very nice answer, and it hints at an even nicer general property. If $X,Y$ are topological spaces, then the fundamental group of their cartesian product $X\times Y$ is equivalent to the direct product of their fundamental groups. That is,

This means that the 3-torus, denoted $T^3$, which is the cartesian product of three circles $S^1\times S^1\times S^1$, has fundamental group $\mathbb Z^3$, and so on. It can also be shown that a 2-torus $T^2$ with $n$ holes poked in it (or, more precisely, $n$ points deleted) is equivalent to $F_n$ for $n\ge 1$:

Now I’d like to showcase a more complicated example, but to do so I will have to take advantage of a useful result known as Van Kampfen’s Theorem and use something called a free product with amalgamation, which is a generalization of the free product operation $*$ described earlier. I’ll use an intuitive explanation for the following example instead of going into the nuts and bolts, but just know that a more rigorous proof of the following result would probably make use of Van Kampfen’s Theorem and the amalgamated free product.

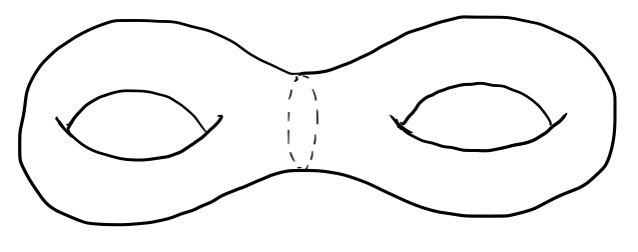

Suppose now that we want to find the fundamental group of a double torus, or a torus of genus 2, which looks like two donuts joined together:

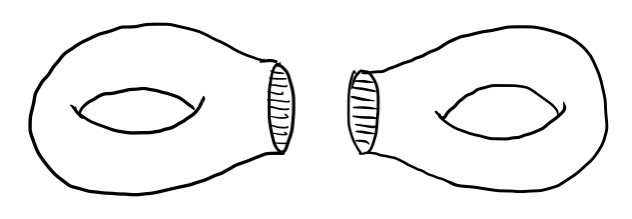

Notice that this is not equivalent to the wedge sum of two tori. They aren’t joined together at a single point, but rather with a hollow tube. To figure out the fundamental group of this scrumptious surface, let’s cut it in half, like this:

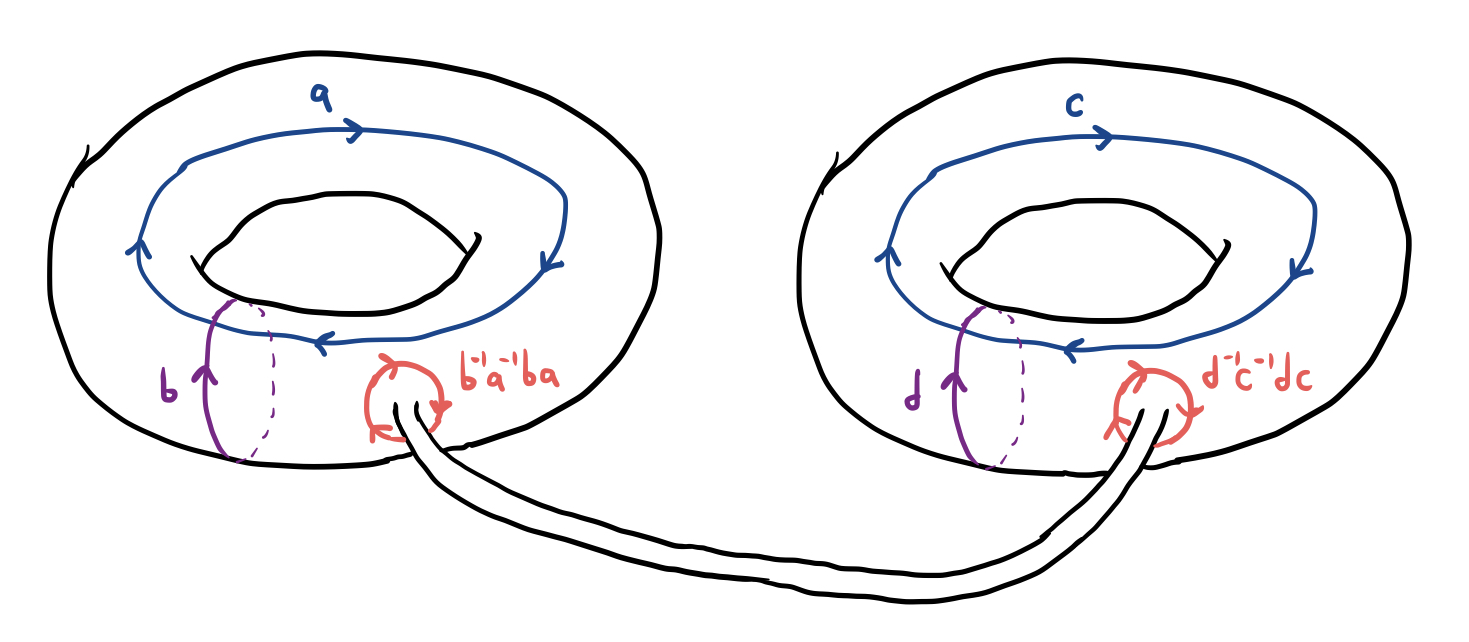

It looks like each half is equivalent to a punctured single torus, and we remarked earlier that the fundamental group of a punctured torus is the free group $F_2$. If we let $a,b$ be the generators of this free group as shown in the image below, it turns out that $b^{-1}a^{-1}ba$ is equivalent to a loop that circles once around the torus’s hole:

But we’re dealing not just with one punctured torus, but two punctured tori whose punctures are joined together by a long tube. If we let $c,d$ represent the generators of the second punctured torus, we obtain the following picture:

Of course, the tube wasn’t this long when I first drew the double torus, but like I said before, a little bit of twisting and stretching won’t actually change the fundamental group of a topological space. Now notice that if you slide the loop $b^{-1}a^{-1}ba$ like a rubber band along this tube until it sits on the surface of the other torus, it will be oriented in the opposite direction as the loop $d^{-1}c^{-1}dc$. This means that $b^{-1}a^{-1}ba$ and $d^{-1}c^{-1}dc$ are actually inverses:

or we could also write

This means that the fundamental group of the double torus is given by the following strange group presentation:

The torus of genus $3$ (made of $3$ connected donuts) and tori of higher genus have similar fundamental groups, but with many more generators (the fundamental group of the torus of genus $n$ has $2n$ generators).

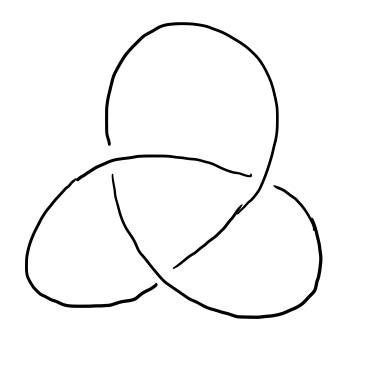

Another fun use of fundamental groups is to calculate the knot group of a knot in $\mathbb R^3$. A knot can be defined similarly to a loop in 3-space, with the added constraint that when continuously deforming a knot into another knot, it cannot be passed through itself like a loop can. In this way, knots are more like actual pieces of string or rope than a loop. For instance, the following knot, called the trefoil knot, cannot be untangled without passing it through itself, meaning that if you construct it out of actual string, you will be unable to untangle it.

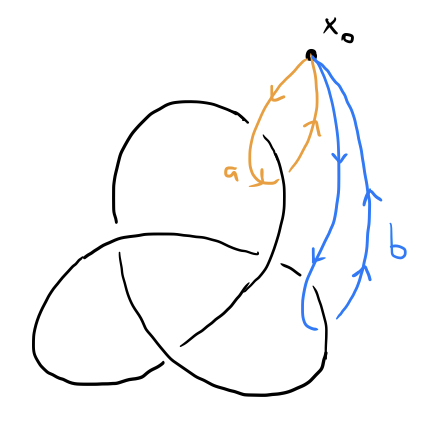

The knot group of a knot $K$ is defined as the fundamental group of $\mathbb R^3\backslash K$, or the complement of $K$ in $\mathbb R^3$. Intuitively, the knot group catalogues all of the ways in which a loop can tangle around a knot. For example, the knot group of the unknot, which is just an untangled loop of string, is equal to $\mathbb Z$, and the knot group of the trefoil knot is given by

where $a$ and $b$ represent the following oriented loops around the trefoil knot:

I won’t explain why in this post, but although it’s a bit trickier to visualize than the double torus, it can also be done using Van Kampfen’s theorem.

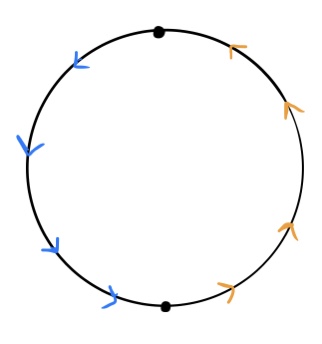

Some really strange surfaces can also give us interesting fundamental groups. Consider, for example, the projective plane, which is really hard to visualize (and, in fact, is not embeddable in 3-space, meaning that you can’t actually make a projective plane in $3$ dimensions). The projective plane can be defined as the surface obtained by taking a two-dimensional circle, dividing its circumference into two parts, and stretching and twisting it until the two parts are “glued together” so that the blue arrows map on to the orange arrows:

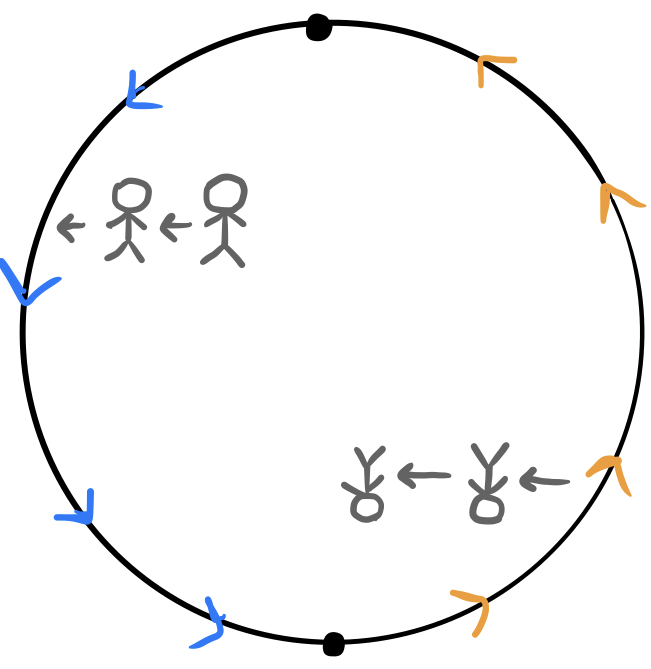

It’s a little bit difficult to visualize, but it helps to think of the circumference of the circle as a “portal” so that one side “wraps around” to the other side in the opposite direction. If you were a little two-dimensional man scooting around on this surface, here is what would happen if you crossed the circumference:

Now, it happens that the fundamental group of this space is equal to $\mathbb Z_2$, which is the two-element group ${0,1}$ with $0+0=0$, $0+1=1+0=1$, and $1+1=0$. It seems unbelievable at first that there are exactly two non-equivalent loops on this surface, but it is true, and here they are, labelled with $0,1\in\mathbb Z_2$:

To understand why the loop labelled $1$ doesn’t generate infinitely many new loops when it is composed with itself, as the loops in the torus or punctured plane do, we need to visualize how it is its own inverse (since $1+1=0$ in $\mathbb Z_2$). But it’s actually not that hard to show that this loop is its own inverse, since twisting it around produces an identical loop in the opposite orientation:

And with that strange example, I’ll conclude this blog post. I hope to return to this topic in a future blog post, since calculating the fundamental group of various weird topological spaces is a fun and mind-bending puzzle. For any reader who is interested in this topic, here are a few more related puzzles:

- Return to the earlier setup involving a picture frame with a loop of string and $4$ nails in the wall. Can you wind the string around these nails so that removing any two nails will cause it to fall, but removing any one nail does not cause the picture to fall?

- Suppose you have a tetrahedron (triangular pyramid) made out of wire. Can you pass a loop of string through this wireframe tetrahedron so that cutting any one of its edges causes the loop to be disconnected from the tetrahedron? (The answer to this is quite messy.)

- The Borromean Rings are three loops that are inseparable from each other, yet no two of the loops are actually joined together:

If you make this out of string, cutting any one of the loops will cause the other two to be separable. Can you find a way to link $n$ closed loops of string together so that cutting any one of the loops causes all of the other $n-1$ loops to be separable? - Consider the following strange surface similar to the projective plane, formed by “gluing” all three edges of a triangle onto the same line segment, so that the red, blue, and green arrows map onto each other, forming a sort of three-way “portal”:

What is the fundamental group of this space?