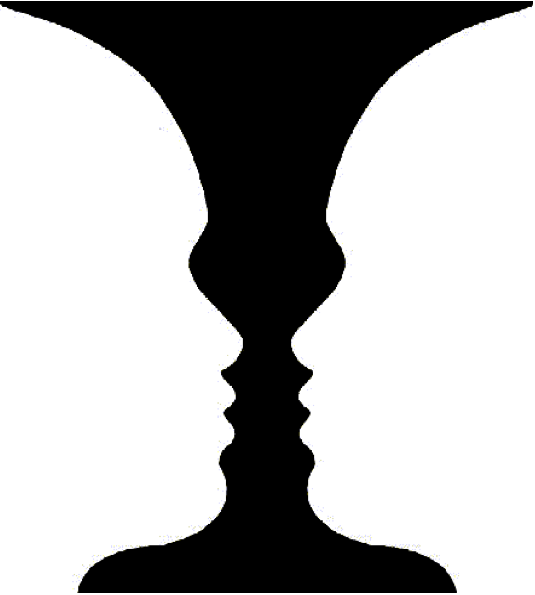

You’ve probably seen the following famous picture (or some variation of it) before:

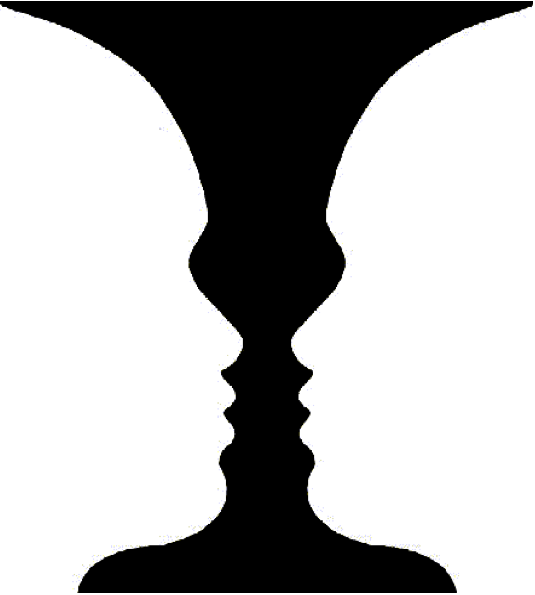

Is it two black faces in the foreground over a white background, or a white goblet in the foreground over a black background? Of course there’s no definite answer to this question - this picture is ambiguous, meaning that it has more than one possible interpretation. There are lots of visually ambiguous pictures like this, such as the famous Necker Cube:

We can’t tell what configuration the depicted cube is in because there’s no indication of which edges or faces are in front of the others. Really, there aren’t just two possible interpretations of this picture, but infinitely many, because we could be looking at a small cube close up, a large cube far away, or anything in between. When a three-dimensional object like a cube is depicted using only two dimensions in a flat image, some information is lost. This makes sense, since it’s not always possible to translate information from one medium to another without some information loss or errors, especially when cramming complex three-dimensional information into two measly dimensions.

I can’t resist including the following classic use of deliberate visual ambiguity to humorous effect:

However, I don’t want to spend too much time just looking at optical illusions and trick photography. The focus of this blog post is ambiguity in language - when some phrase or sentence, spoken or written, has more than one possible meaning. It’s a fun puzzle to deliberately construct ambiguous phrases or look for alternative meanings of sentences in a text while reading. However, in addition to this, analyzing ambiguity in language (and comparing it across languages) tells us something very interesting about the nature of human language and how our brains process language. I’ll spend the majority of this post dissecting and classifying various (often silly) examples of linguistic ambiguity and comparing across languages (mostly just between English, Spanish, and German). Towards the end of the post, I’ll briefly discuss the relevance of this analysis to the way humans naturally parse language.

Before jumping into language syntax, it would be helpful to first consider a mathematical example of ambiguity. Suppose I asked you (verbally) to compute “two times one plus three.” There’s clearly some ambiguity in this request: I could be asking you to compute twice the sum of one and three or the sum of twice one and three Similarly, if I asked you to calculate “one plus three squared,” I could either be referring to or This is why your middle school math teacher made such a big deal about PEMDAS. Mathematics is supposed to be an extremely precise language, which means that misunderstandings or equivocations need to be avoided at all costs. When we write a mathematical expression, it should refer to one thing and one thing only, not multiple possible things. When dealing with arithmetic and operations like addition, multiplication, and exponentiation, a standardized order of operations, coupled with the careful use of parentheses, is used to resolve ambiguity. For an example of parenthesization gone wild, see this question from Mathematics Stack Exchange.

The most obvious examples of linguistic ambiguity arise from words like “bear” and “bare” that sound the same, or words that can serve as more than one different part of speech, like “man,” which can be either a noun or an adjective.

But I’m not just going to fill this blog post with a long list of words like this, because not only are they the most boring type of linguistic ambiguity, but they also aren’t actually very common. When we communicate with each other, we don’t just blurt out words or phrases. We (usually) speak and write in full sentences, and the context provided by other words in a sentence helps us eliminate ambiguity. If someone says to me

“Meet me here at the same time tomorrow.”

I won’t wonder whether or not they intended to say

“Meat me here at the same time tomorrow.”

because that just doesn’t make any sense. “Meat” is almost always a noun, so the second sentence doesn’t contain any verb, and is completely grammatically awry. However, if someone tells me

“I have to go shopping for vegetables and meet for lunch with my friend.”

I really might not be sure whether the speaker intended to say

“I have to go shopping for vegetables and meat for lunch with my friend.”

In the second sentence, some other things are also unclear too. Are you going shopping with your friend, or eating lunch with your friend? Are the vegetables and meat both for lunch, or just the meat? I want to explore this kind of complex grammatical ambiguity, not just list a bunch of words with multiple meanings. Something happened in that sentence that allowed a certain word to serve either as a noun or a verb. What’s going on?

Let’s take a step back and talk about what exactly a sentence is. First of all, our language is creative, meaning that we can form sentences that we’ve never read or heard before by applying a few rules. Unlike many animals with a finite number of “signals” that have fixed meanings (bark means “I’m excited,” tail wag means I’m happy, butt sniff means “let’s get to know each other,” etc.), we can combine words and phrases in new ways to convey new ideas that we haven’t learned anywhere else and that certainly aren’t hardwired into our brains. If I so choose, I can create the sentence

“Today I saw a purple octopus with a top hat scuttling down the street.”

even though I’ve certainly never heard or read it before. Not only that, but I can use it to make you imagine and visualize a ridiculous event that never happened!

Our language is also recursive, meaning that we can build words or phrases and then stick them into other structures or grammatical templates to create arbitrarily long and complex sentences. For instance, take the sentence

“He stinks.”

Now, here’s a nice grammatical structure in the English language that allows me to convey secondhand information: if person X tells me sentence Y, then I can tell you

“X said that Y.”

Suppose my friend Alice tells me “that guy stinks.” If Alice’s observation stands in for Y and Alice stands in for X, then I can say

“Alice said that he stinks.”

Not only that, but if Alice heard this information from Bob, then I can go one layer deeper and say

“Alice said that Bob said that he stinks.”

And if Bob also received this as secondhand testimony from Chad, I can say

“Alice said that Bob said that Chad said that he stinks.”

I could keep going, but you get the picture. This is of course only a simple example; we apply many such templates and substitution rules in everyday conversations, and surely many more in formal writing.

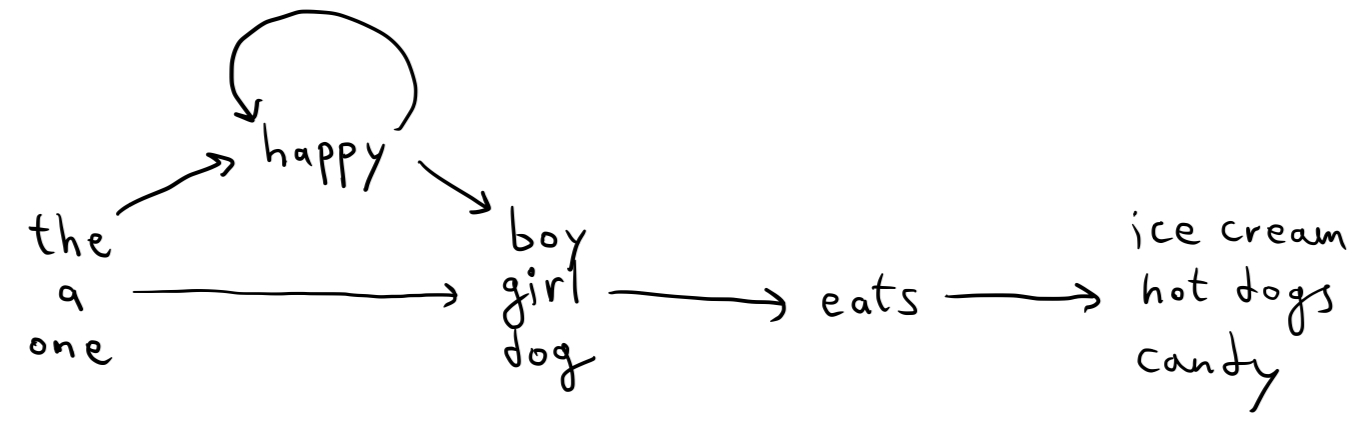

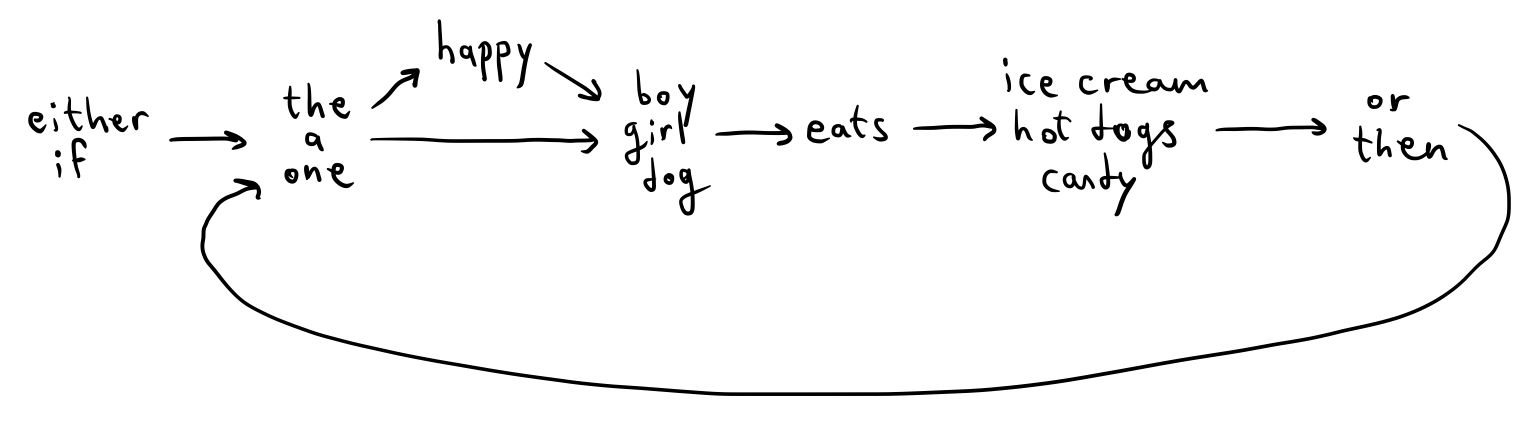

Linguists have been trying for a long time to formalize and model the process that we use to build and parse sentences. In The Language Instinct, Steven Pinker mentions a model called a word-chain device that was proposed as the mechanism by which we form recursive sentences. Here’s an example borrowed from Pinker’s book:

By starting at “the/a/one” and following arrows until we reach the end, we can form all kinds of grammatically correct sentences, like

“A dog eats candy.”

“The happy boy eats ice cream.”

“One happy happy happy happy happy girl eats hot dogs.”

It seems like a good enough model for this simple example, but Pinker points out that it falls apart when we try to create word-chain devices for more complex sentences. To borrow another example from Pinker, consider the sentences

“Either the girl eats ice cream, or the boy eats candy.” “If the girl eats ice cream, then the boy eats hot dogs.”

This leads to the following word-chain device:

It seems to work at first, but closer inspection reveals that this broken mechanism allows us to produce inanities like

“If the dog eats ice cream or the girl eats candy.”

“Either the boy eats candy then the girl eats hot dogs.”

“If the happy dog eats ice cream then the dog eats ice cream then the dog eats ice cream.”

We could probably salvage this model by introducing some more complicated rules regarding which arrows to follow when, and how many times each arrow can be followed, and so on. But at that point, Occam’s Razor would obligate us to shave the whole thing away. Clearly language is more complex than just a series of movements from one word to the next.

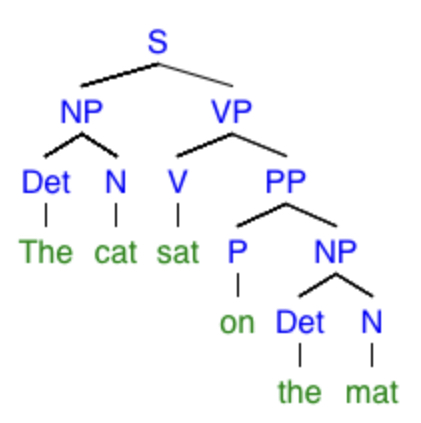

Currently, the prevailing model of grammar in sentences is the syntactic tree, which I will describe momentarily, and which will be very useful for allowing us to understand syntactical ambiguity. However, be warned that I am not a professional linguist, and the syntactic tree model that I lay out might not be the most current version. In fact, there are some particular modules of the syntactic tree that are commonly used, but that would overcomplicate things for the sake of this post (e.g. the complementizer phrase and inflectional phrase). A simplified version of the syntactic tree will suffice for our purposes.

For any reader who isn’t already familiar with syntactic trees, have a look this example, and then I’ll explain what each part means:

This is a syntactic tree for the sentence

The cat sat on the mat.

Here’s a quick description of the types of modules of this tree:

There are more, of course, like AdjP, the adjective phrase, AdvP, the adverb phrase, Adj and Adv, adjectives and adverbs by themselves, and it doesn’t end there. Things get really complicated when considering questions or imperatives, but we don’t need to go there.

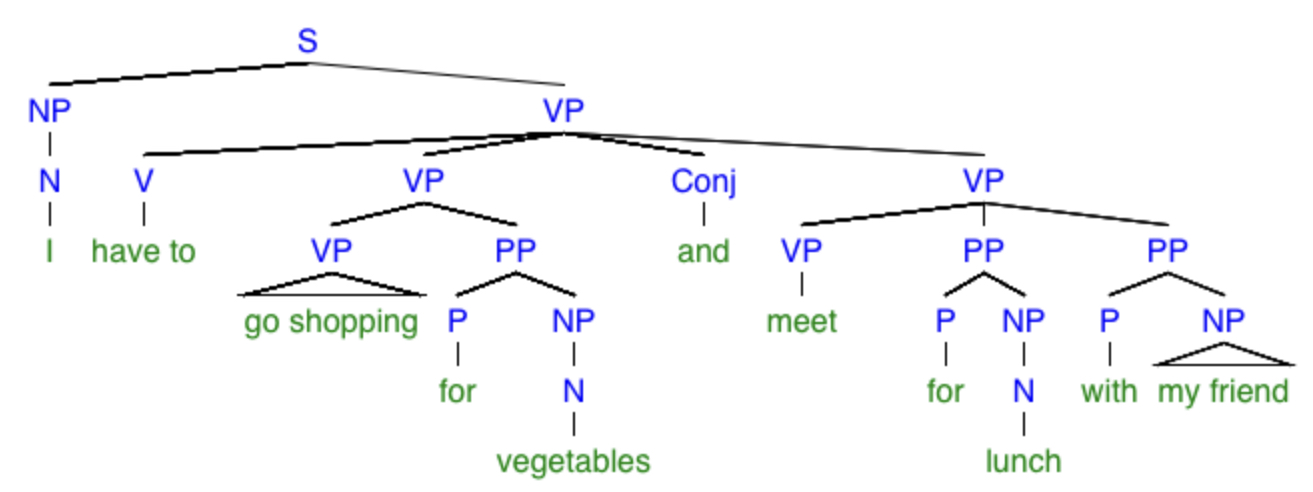

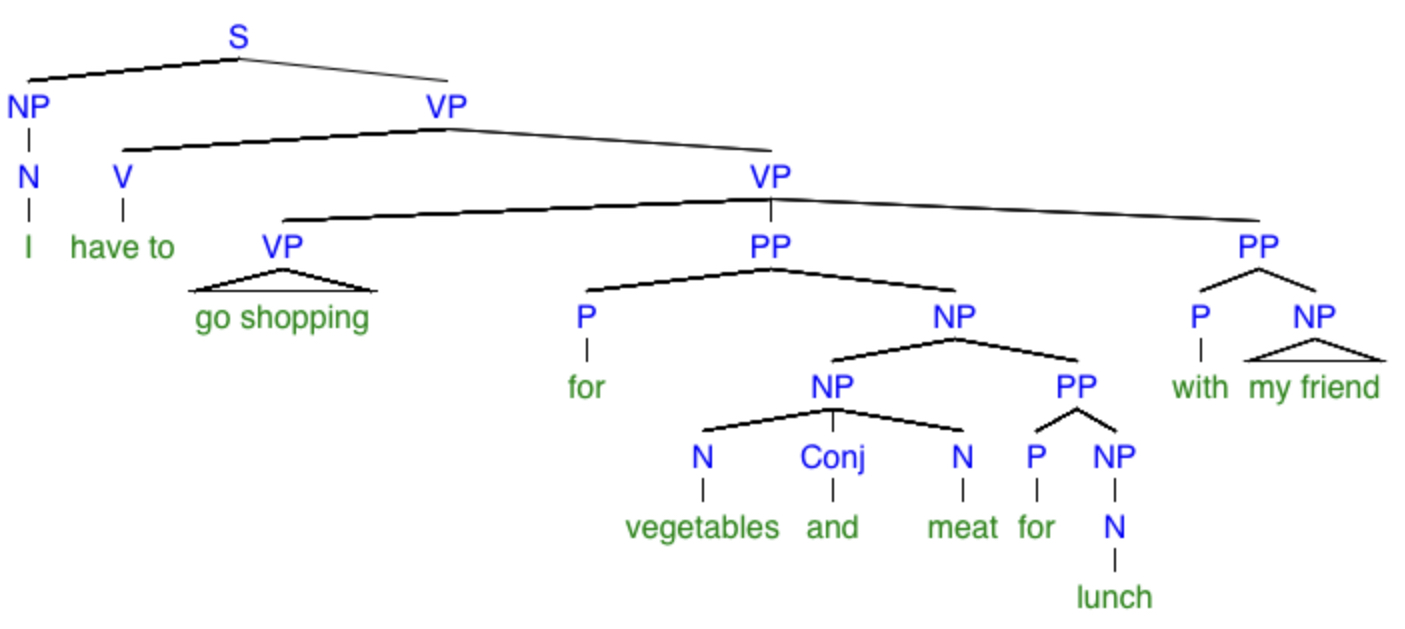

Let’s have a closer look at the example sentence from earlier:

“I have to go shopping for vegetables and meet for lunch with my friend.”

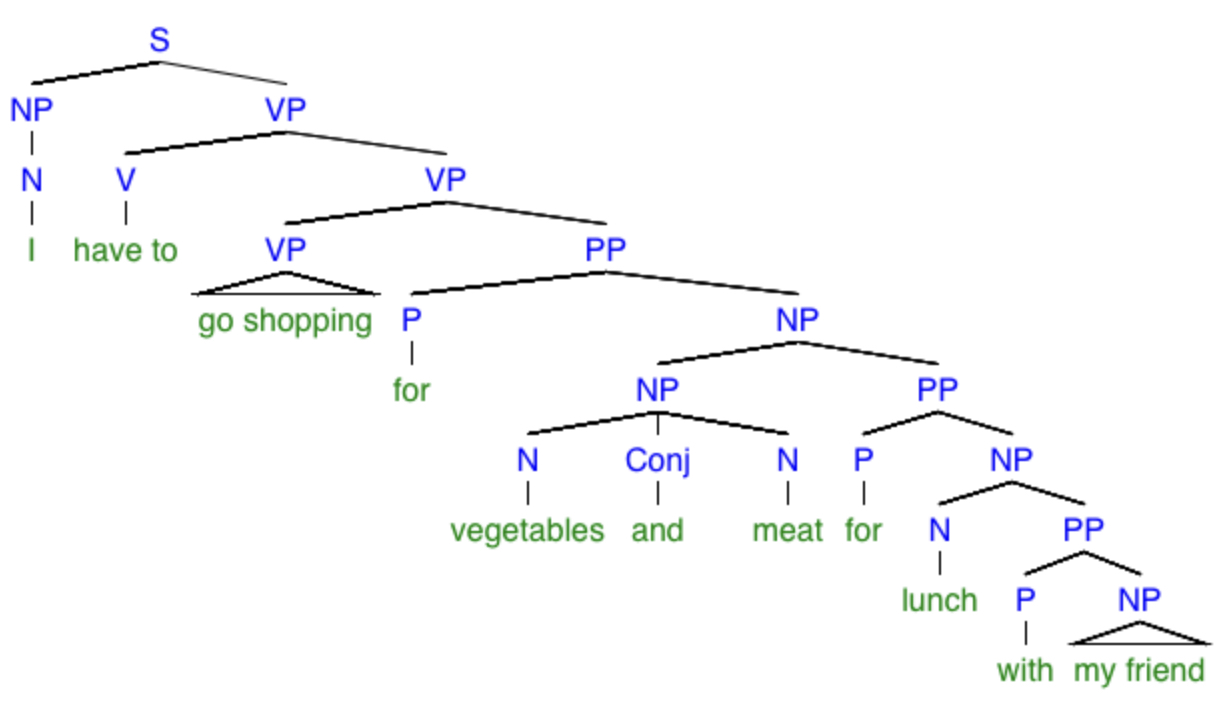

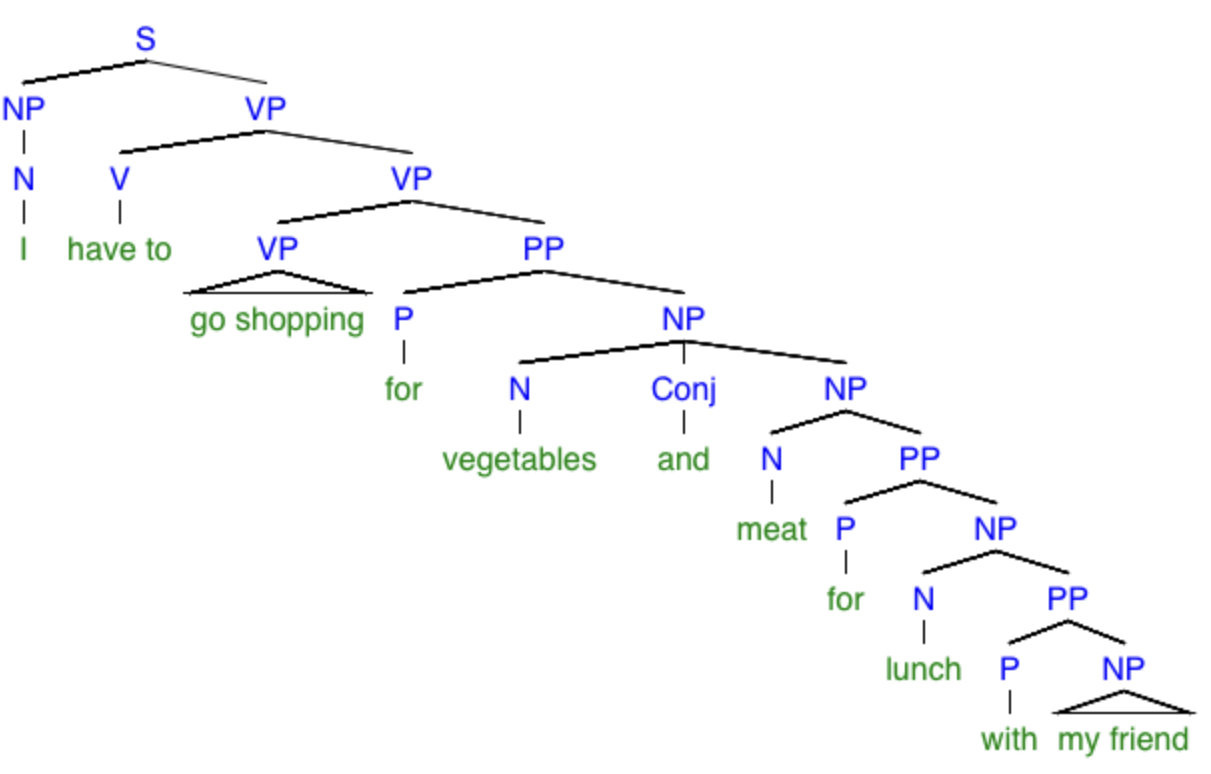

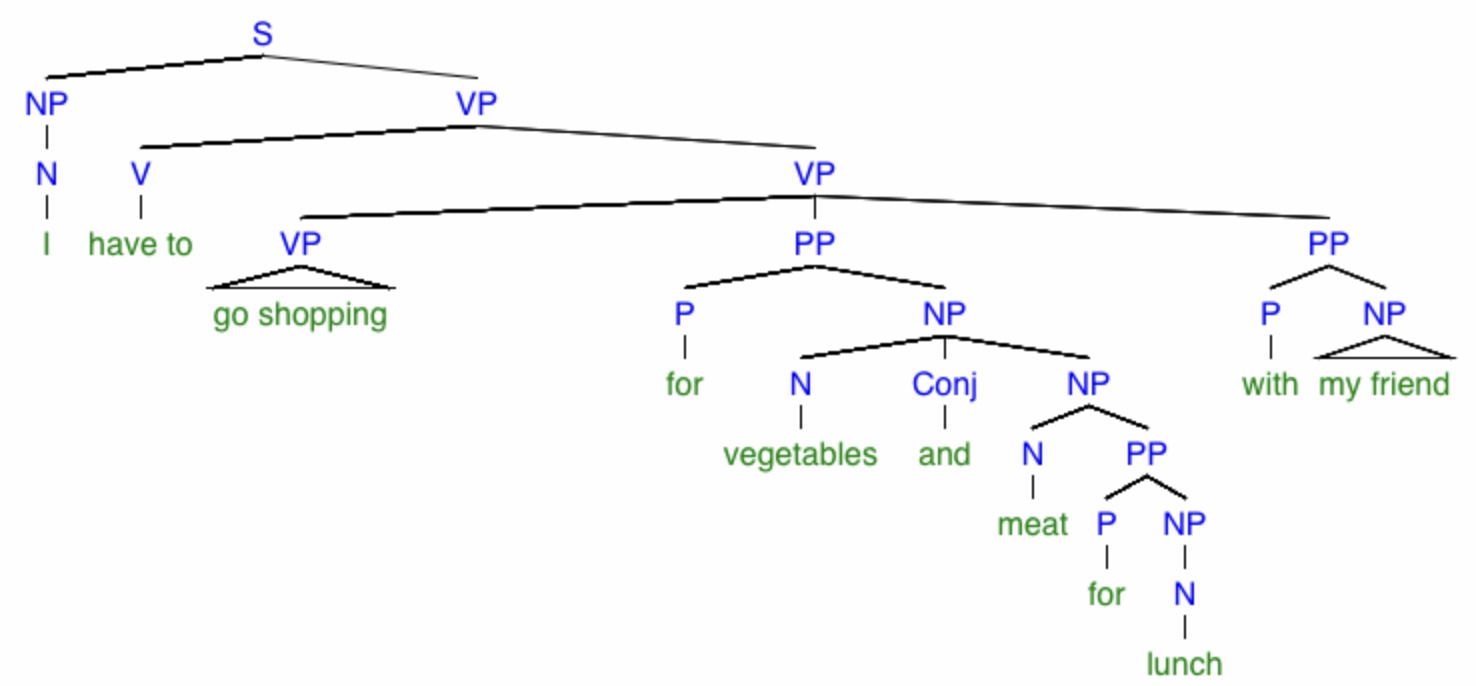

If we take this to be a spoken sentence, we must also take into consideration the phonetic ambiguity between “meet” and “meat.” I detect at least five different possible meanings, and they can be represented by the following trees:

What monstrosities! By the way, the little triangles mean “there should be some more branches in here but I’ve left them out.” Again, be warned that my dissection of this sentence might not be exactly correct (for instance, I’m not sure if the verb phrase “go shopping” should instead be the noun phrase “to go shopping”), but it at least demonstrates my point that a simple sentence can have many possible meanings. To facilitate reading these trees, here are explanations of the specific meanings of the sentences in each one, respectively:

That was a pretty complicated example. To really isolate and understand different sources of ambiguity, we’ll have to deal with some simpler examples. However, before moving on, I’d like to make an analogy that helps (me, at least) understand why such ambiguity occurs. As the syntactic tree indicates, the actors, actions, and abstractions in a typical sentence interact in a tangled web of nested relationships. When we attempt to pack all of this information into a single linear sentence, we lose information in the same way that we lose information when we draw a three-dimensional cube on a two-dimensional piece of paper. Loading up a simple sequence of words with so much relational information for the reader/listener to unpack is almost like compressing data on a computer, sending it somewhere else, and decompressing it on another device.

The examples of ambiguity in language that most easily come to mind are those caused by these three common culprits:

In languages like Spanish and German whose words have genders, sometimes the meaning of a word depends on its gender. “El corte” means a cut or edge, while “la corte” refers to a royal court. “Der Moment” means an instant in time, while “das Moment” can refer to physical momentum. There even exist autoantonyms, or words that can take on two opposite meanings (called Januswörter in German, based on Janus, the two-faced Greek god), like “inflammable” in English.

Like I said earlier, this type of ambiguity by itself isn’t very interesting. There really isn’t much to analyze in sentences like

“John went to the bank.”

“That dog smells.”

“Er starb nach einem Kampf gegen einen starken Krebs.”

in which two or more meanings of a particular word are interchangeable without changing the structure of the sentence. It’s worth noting, however, that this type of ambiguity runs amok in Spanish verbs, since the first-person and third-person conjugations of verbs in the imperfect and subjunctive tenses are often identical. For instance, the simple sentence

“Lo tenía.”

Could either mean “I had it” or “he had it.” Also, the present-tense conjugations for verbs in third-person and formal second-person are always identical. Thus, the sentence

“¿Tienen hambre?”

could mean “are they hungry?” or, formally, “are y’all hungry?” In English and German, this doesn’t happen often because every sentence has to have an explicit subject. However, in German, the third-person plural pronoun “sie” sounds identical to the formal second-person singular pronoun “Sie,” so the sentences

“Haben Sie Hunger?”

“Haben sie Hunger?”

are distinguishable on paper but not in speech.

Here’s an example of a sentence that is ambiguous because of a homonym, but its alternate meanings have different structures:

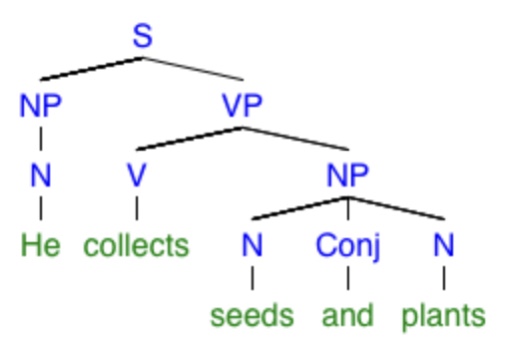

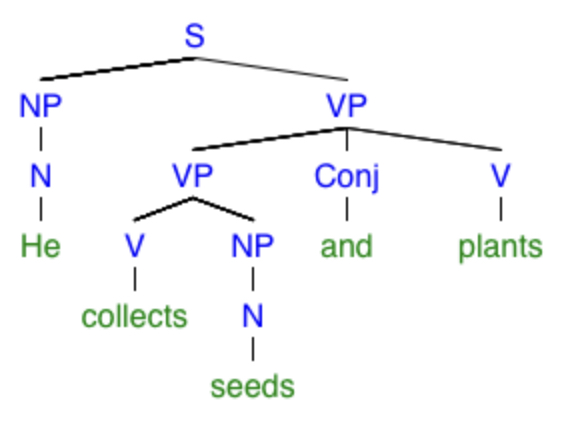

“He collects seeds and plants.”

It’s not as drastic of a structure change as in the earlier example with “meet” and “meat,” but here are the two trees representing its possible meanings:

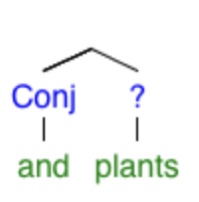

Because the two meanings of “plants” are different parts of speech, the structure of the tree can’t be preserved. The difference between the two trees above is the position of this “twig”:

The “and” can conjoin a noun to another noun or a verb to another verb, but not a verb to a noun. When “plants” is a noun, “seeds and plants” makes sense and “collects and plants” does not, but the opposite is true when “plants” is a verb. Interestingly, this kind of confusion couldn’t happen in written German, since all nouns are capitalized. Also, German is a V2 word order language, meaning that the second word in a sentence/clause must be its verb.

In many sentences, however, no words change meanings at all - only the relationships between the words change. Consider, for example, the sentence

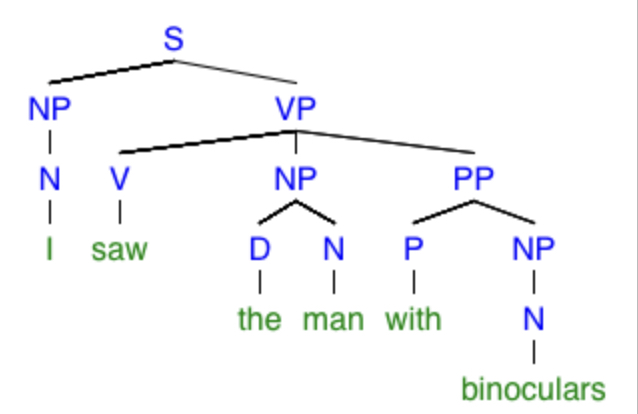

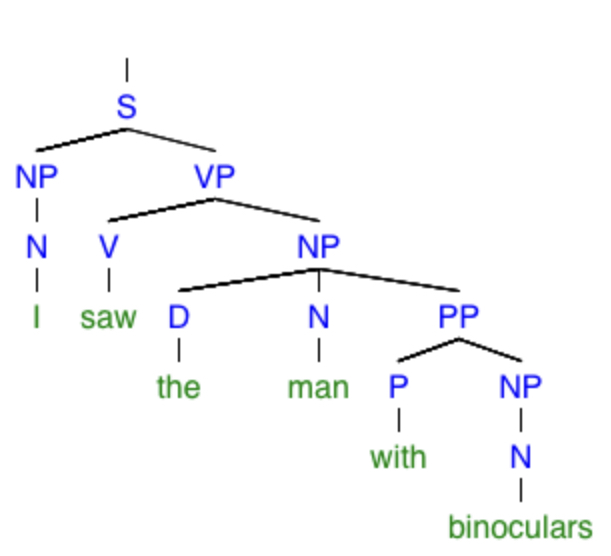

“I saw the man with binoculars.”

The trees corresponding to the two possible meanings of this sentence are given by

Either I looked at a guy using binoculars, or I looked at a guy who had binoculars. In this case, the prepositional phrase “with binoculars” is causing trouble, since it can modify either “saw” or “the man.” Actually, prepositional phrases cause all kinds of trouble, as in each of the following sentences:

“The dancers leapt, twisted, and turned on the television.”

“We have to liberate the prisoners from the American embassy.”

“Please put the cake on the plate in the fridge.”

“Der Schmetterling verwandelt sich in einem Baum.”

The second-to-last sentence could mean that a butterfly in a tree is metamorphosing, or that it is actually morphing into a tree (the same trick works in English, and you may recognize it from the old joke about a car turning into a driveway). Prepositions can really cause confusion if we nest them multiple times in long sentences, like this:

“Put the cake in the box in the fridge.”

“Put the cake in the box in the fridge in the corner.”

“Put the cake in the box in the fridge in the corner in the kitchen.”

“Put the cake in the box in the fridge in the kitchen in the neighbor’s house.”

The first sentence has $2$ possible meanings, the second has $3$ possible meanings, the third has $4$, the fourth has $5$, and as you can probably guess, a similar sentence with $n$ prepositional phrases tacked onto the end will have $n$ possible meanings. However, the preposition “in” is harmless compared to something like “next to.” If we know that X is in Y and Y is in Z, then we can conclude that X is in Z, making “in” a transitive relationship. However, if X is next to Y and Y is next to Z, it does not follow that X is next to Z. Consider the following sentences:

“Put the cake next to the pie next to the stove.”

“Put the cake next to the pie next to the stove next to the window.”

“Put the cake next to the pie next to the stove next to the window next to the clock.”

“Put the cake next to the pie next to the stove next to the window next to the clock next to the fridge.”

In this case, the first sentence has $2$ possible meanings:

“Put the cake next to (the pie next to the stove).”

“Put (the cake next to the pie) next to the stove.”

But the second sentence has $5$ possible meanings:

“Put the cake next to (the pie next to (the stove next to the window)).”

“Put the cake next to ((the pie next to the stove) next to the window).”

“Put (the cake next to the pie) next to (the stove next to the window).”

“Put (the cake next to (the pie next to the stove)) next to the window.”

“Put ((the cake next to the pie) next to the stove) next to the window.”

The third sentence has $14$ possible interpretations, and the fourth sentence has $42$. If you’re curious, the number of possible interpretations of a sentence like this with $n$ prepositions at the end is equal to the nth Catalan Number, meaning that it grows exponentially. Of course, nobody would ever say sentences like these, but if you’re a theorist like myself, you’ll find them fascinating anyways.

Prepositions aren’t the only parts of speech that cause such trouble. Almost any word that refers to another word can be similarly ambiguous. For instance, the adjective in the following sentence creates ambiguity in the same way as the prepositions in the previous examples:

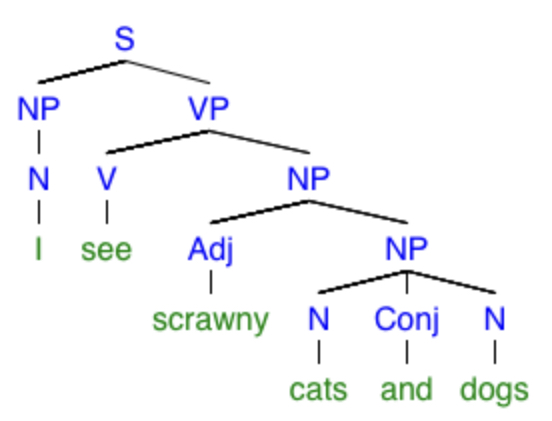

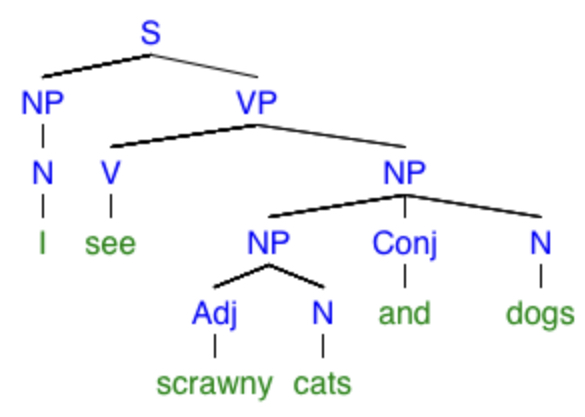

“I see scrawny cats and dogs.”

Are the dogs scrawny too, or just the cats? Here are the trees corresponding to the two interpretations of this sentence:

In Spanish, different kinds of ambiguity can be created using adjectives because they follow the nouns they modify, rather than preceding them as in English. For instance, the sentence

“Ella le gritó a su madre enojada.”

could either mean that a lady shouted at her angry mother, or an angry lady shouted at her mother. However, sometimes the requirement of gender agreement between an adjective and its referent eliminate ambiguity, as in this sentence:

“Él le gritó a su madre enojada.”

There’s no confusion here - the word “enojada” refers to the dude’s “madre”. If it referred to him, it would have to be “enojado.” German takes this even farther by requiring adjective endings that not only must agree in gender, but also in case (distinguishing between subjects, direct objects, indirect objects, etc.).

However, there is one variety of ambiguity that can occur only in German, not in Spanish or English. In sentences like

“Viele störenden Vögel vertreiben die Geschäftsleute.”

the subject and the direct object of the verb are unclear. This sentence could be telling us about some businessmen chasing away a bunch of annoying birds, or a bunch of annoying birds chasing away some businessmen. Personally, I find it surprising that a language that insures against so many other kinds of ambiguity (by anally requiring case endings and V2 word order) would allow for confusion about something as crucial to the meaning of the sentence as its subject and object.

To summarize, there are three main types of syntactic ambiguity that I’ve noticed in English, Spanish, and German:

Another thing that I find extremely interesting is the fact that some languages protect against ambiguities that I didn’t even realize ran amok in English. For instance, the sentence

“He ran in the gym.”

could either indicate that someone ran around inside of a gym, or that someone ran into the gym from outside. In German, these two possibilities would be expressed respectively by the following two sentences:

“Er lief in die Sporthalle.”

“Er lief in der Sporthalle.”

There are many other examples of this in other languages. In Spanish the verbs ”ser” and “estar” would both translate into the verb “to be” in English, but they distinguish between permanent, essential characteristics (“He is a human” or “It is brown”) and transient, circumstantial ones (“He is happy” or “It is on the shelf”). Some languages like Sanskrit, in addition to just having singular and plural numbers for nouns, also have a dual case, referring to exactly two objects. Some languages even add affixes to words or statements to indicate how certain the speaker is of the information being communicated, whether the speaker heard the information secondhand from someone else, and so on. Alas, if only I knew some more languages, then I could list more examples here.

In English, we have $26$ different letters, meaning that the number of possible words with $n$ letters is equal to $26^n$. This means that the number of possible five-letter words is equal to

Okay, I’ll admit that some of these words, like “kqqxv,” would be virtually unpronounceable. But even if we only counted words in the much more pronounceable form “CVCVC,” where “C” stands for a consonant and “V” stands for a vowel, the number of words would be

However, the English language has fewer than $250,000$ words, and that includes thousands of archaic and obsolete words. If you think about it, there’s no good reason for us to have any words with more than five letters, since there are vastly more five-letter combinations than words that we currently use. So why the heck do we have homonyms with more than one possible meaning packed into a single word? There are clearly more than enough letter/sound combinations for us to give each concept its own word.

Of course, languages aren’t designed, but evolved. Prehistoric humans did not all sit down together and collectively decide to make a language - it formed naturally and gradually. Even modern attempts to standardize and control language are usually futile, because no single authority can control how thousands and thousands of people speak on a daily basis. Existing words undergo subtle changes in meaning, new words form as memes spread through a population, existing languages mix together during intercultural interactions, and slang forms. This all suggests that language is probably influenced more by evolutionary laws than deliberate human attempts to improve it by, say, reducing ambiguity.

But even an evolutionary perspective seems to suggest that a living, evolving language should tend to become less ambiguous. Wouldn’t a population of people with a more ambiguous language be more prone to misunderstanding? Shouldn’t the group of people with the most efficient and least ambiguous language have a better chance of survival?

Some have suggested that some amount of ambiguity actually makes a language more efficient, not less. The human brain is really good at making subtle inferences, reading between the lines, and making good guesses about missing information based on context and prior knowledge. Therefore, a language that eliminates as much ambiguity as possible might be extremely cumbersome to speak, whereas loosening things up by allowing a little bit of uncertainty, which the listener could easily (in fact, almost automatically) resolve, might save the speaker a lot of trouble while making communication only slightly less reliable.

If you think about your everyday exchanges in spoken and written language, this should ring true. How often does a grammatically ambiguous sentence actually cause a significant misunderstanding between you and another person? Although the esoteric and convoluted language present in bureaucratic forms and legal documents can produce frequent ambiguities with real and weighty consequences (which Pinker discussed briefly in The Language Instinct), these types of confusion wouldn’t have affected our ancestors while language was first emerging.

In fact, most real-life examples of ambiguity that come easily to mind are deliberate and intended humorously. Homonyms and homophones feature ubiquitously in cheesy jokes like

“What did the fast tomato say to the slow tomato? ‘Ketchup!’”

“Did you hear about the guy whose whole left side was cut off? He’s all right now.”

“One morning I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got into my pajamas I’ll never know.”

“Time flies like an arrow, and fruit flies like a banana.”

...not to mention that every single one of those telephone pranks that Bart and Lisa Simpson play on Moe the Bartender makes use of phonetic ambiguity between a name (“Amanda Huggenkiss”) and some potentially embarrassing phrase that the hapless Moe is tricked into shouting across the bar (“a man to hug and kiss”). There’s also a whole class of puns revolving around phonetic ambiguity in Japanese, and some of them are quite amusing (although I’m sure they would be even more amusing if I spoke Japanese).

So the reality is that ambiguity probably adds value to a language, not just by counterintuitively increasing its efficiency, but also adding all kinds of culturally priceless corny puns. And with that realization, I’ll conclude this blog post. I encourage you, reader, to keep an eye out for ambiguous grammatical structures whenever you’re reading, writing, speaking, or listening. Personally, this not only provides me with unlimited grammatical puzzles and word games with which to fill my idle time, but it also gives me a nice chuckle now and then.