In this post, I’ll explore the geometry of a famous fractal called the Koch Snowflake. This analysis will involve a few newly-defined functions analogous to the trigonometric functions $\sin(x)$, $\cos(x)$, and $e^{ix}$ corresponding to the perimeter of the Koch Snowflake rather than the unit circle.

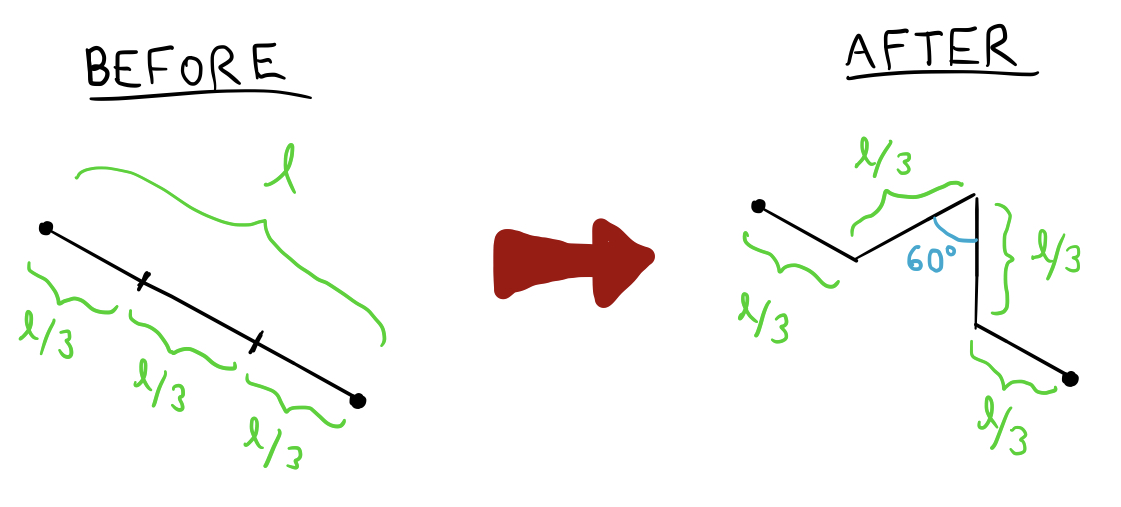

Let’s begin with the list of rules that generates the Koch Snowflake in the Cartesian coordinate plane:

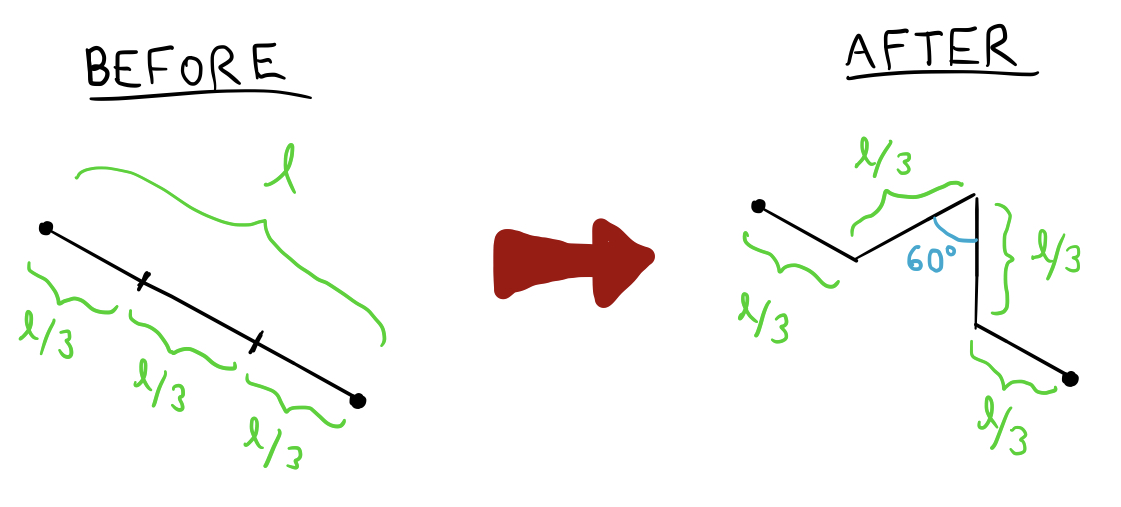

This process results in the following sequence of figures:

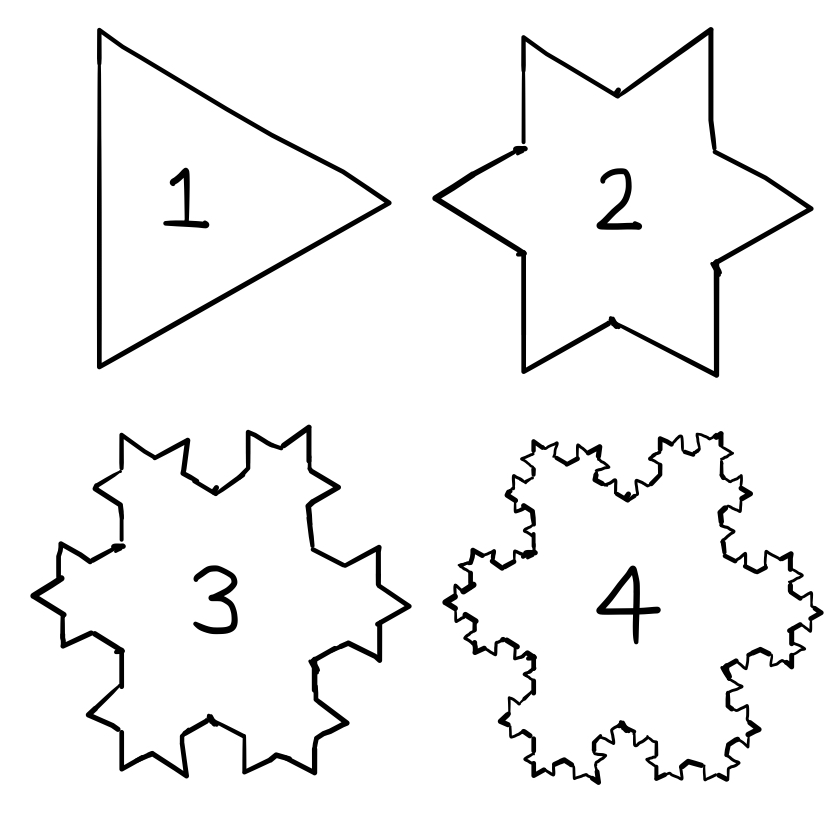

...and eventually, after infinitely many iterations, we obtain the completed Koch Snowflake fractal (thanks to Wikipedia for the image):

First, let’s investigate the area and perimeter of this fractal. The area of the Koch Snowflake can be represented as the limit of the areas of each of its iterations, which results in an easy-to-evaluate geometric series.

Denote the area of the nth iteration by $K_n$, where $K_1$ is the area of an equilateral triangle and $K_{\infty}$ is the area of Koch Snowflake. Recall that the area of an equilateral triangle with side length $l$ is $\sqrt{3}l^2/4$, so we have that $K_1 = 3\sqrt{3}/4$. In $K_2$, three smaller triangles are added to the area of $K_1$, each of which has an area $1/9$ that of $K_1$. Thus, we have In $K_3$, $12$ triangles are added, each with an area still $9$ times smaller, so we have Notice that, in general, $K_n$ is a polygon with $3\cdot 4^{n-1}$ sides. This means that, in general, the area of $K_{n+1}$ consists of the area of $K_n$ plus $3\cdot 4^{n-1}$ smaller triangles with an area $9^{n}$ times smaller than that of $K_1$. Thus, we have Now we may use this recursive formula to express $K_\infty$ as an infinite series:

So we have

Now, if we consider the perimeter of the Koch Snowflake, we get a more interesting result. At each step, every line segment on the snowflake is replaced by a kinked line segment with $4/3$ of the length of the original segment. Therefore, the perimeter of each iteration is $4/3$ times the perimeter of the previous iteration. This implies that the perimiter increases exponentially from one step to the next, diverging to infinity. In other words, although the Koch Snowflake is a bounded figure, it has “infinite perimeter.”

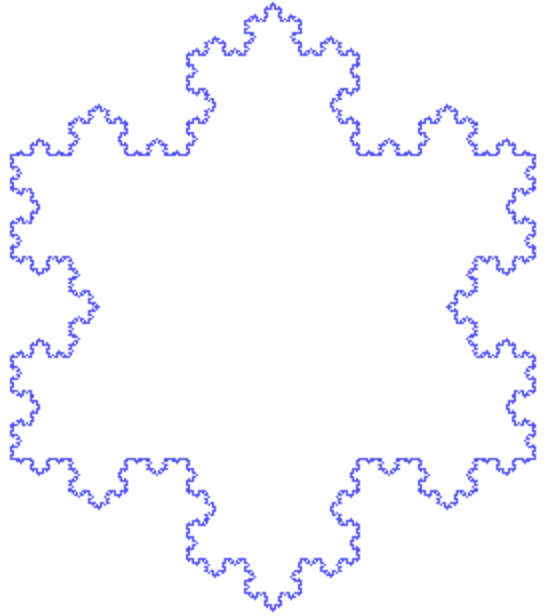

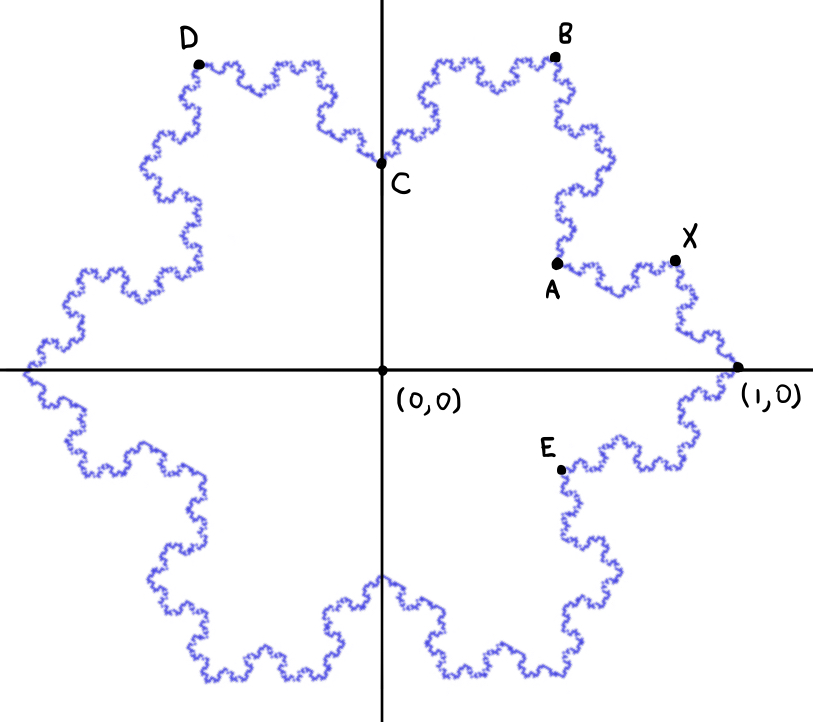

This might make it difficult to do geometry with the Koch Snowflake in the same way that we do with less exotic figures like polygons and circles. However, although it doesn’t make sense to talk about the absolute “length” of the Koch Snowflake’s perimeter, we can talk about it in terms of ratios and proportionality. Take a look at this diagram, in which I’ve labelled some points on the Snowflake’s perimeter:

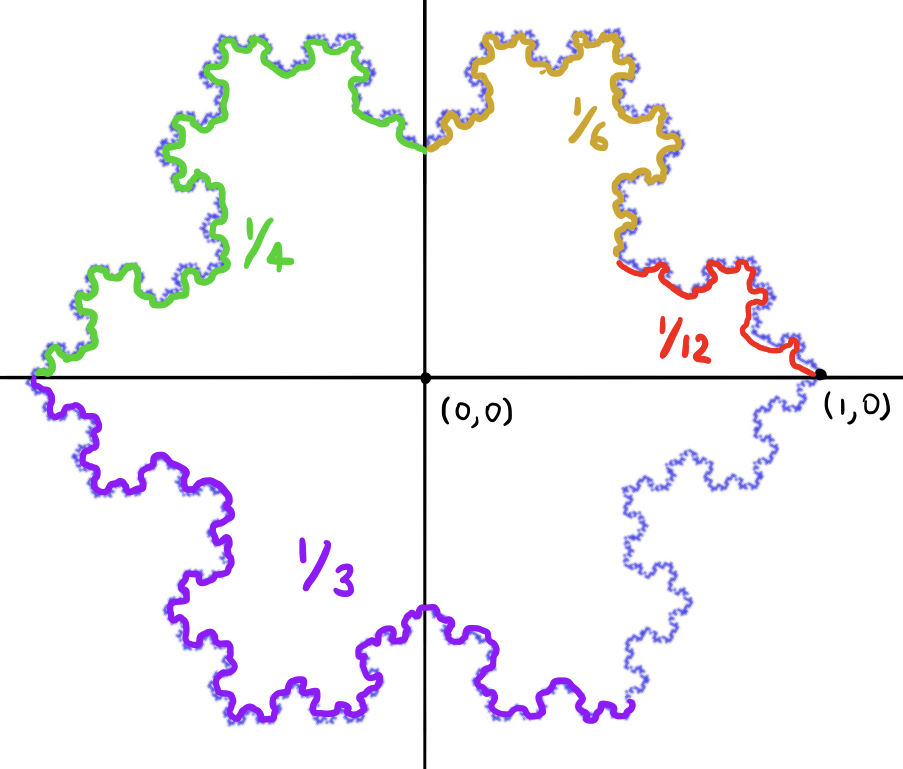

The self-similarity of the Koch Snowflake comes in handy here. Consider, for example, the segment of the Snowflake’s perimeter between $(1,0)$ and $B$. It doesn’t make sense to refer to the “length” of this segment. However, it does make sense to say that the point $A$ is halfway between $(1,0)$ and $B$ along the perimeter, because it “bisects” that segment into two congruent segments. Similarly, we may say that $1/3$ of the Snowflake’s total perimeter lies between $(1,0)$ and $D$, since the entire Snowflake is constructed from three congruent copies of the same shape. By the same reasoning, we may say that $1/4$ of the Snowflake’s length lies between $(1,0)$ and $C$, or that $1/12$ of the snowflake’s length lies between $(1,0)$ and $A$.

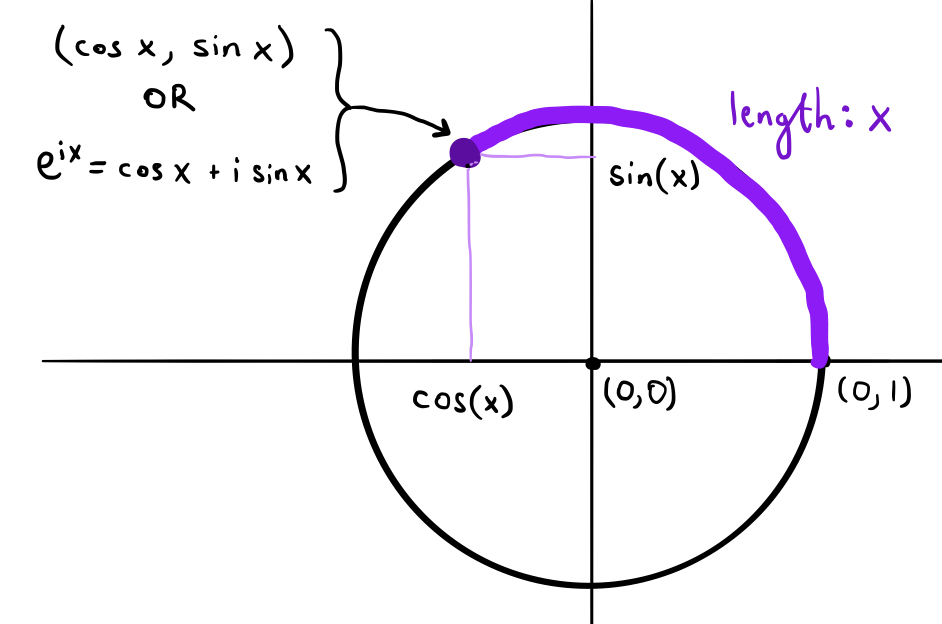

Let’s briefly pause our consideration of the Koch Snowflake to consider another example of a geometrical figure whose length is troublesome to calculate: the circle. We are forced to make use of the enigmatic symbol $\pi$ to refer to the circumference of a circle, because we know of no other elementary way to represent it. When we do geometry involving circles, we make use of the trigonometric functions $\sin(x)$ and $\cos(x)$, which translate proportions of the unit circle’s arclength into x- and y-coordinates that are easier to work with. More preciseley: if the counterclockwise arc from $(1,0)$ to $P$ on the unit circle covers a proportion $p$ of the arclength of its upper half, then the x-coordinate of the point is $\cos(\pi p)$, and its y-coordinate is $\sin(\pi p)$.

We can also refer to points on the unit circle in complex exponential form. For example, $e^{i\pi/2}$ refers to the point halfway around the top half of the unit circle (moving counterclockwise), $e^{i\pi/3}$ refers to the point one third of the way around, and so on.

We can do something analogous with our Koch Snowflake. Let’s pretend for a moment that the upper half of our Snowflake does have an actual length, and call this length $L$. Instead of using the complex exponential function $e^{ix}=\exp(ix)$, we can define our own special function that refers to points on the Koch Snowflake rather than the unit circle. Let’s call the function $\text{kxp}(x)$. We can define it (non-rigorously) as follows: if $L$ is the “length” of the upper half of the Koch Snowflake, then $\text{kxp(Lp)}$ refers to a point in complex form on the Snowflake’s perimeter such that the counterclockwise arc from $(1,0)$ to the point covers a proportion $p$ of the Snowflake’s upper half. That was a mouthful, so let’s do a few examples.

Refer to the diagram above on which I labeled points $A,B,C,D,E,$ and $X$ on the “Unit Koch Snowflake.” Using basic trigonometry, we may actually explicitly calculate the positions of some of these points. First consider point $C$. The position of this point is especially easy to calculate, since it lies on the triangle in the first iteration of the Snowflake - its x-value is clearly $0$, and its y-value turns out to be $\sqrt{3}/3$. Since the segment of the perimeter between $(1,0)$ and $C$ covers half of the Snowflake’s length above the x-axis, or $L/2$, we may write

Next let’s calculate the position of point $B$ and how it translates into a special value of our kxp function. This one is pretty easy to calculate - notice that $B$ is just the image of the point $(1,0)$ under a $60^\circ$ counterclockwise rotation. In the complex plane, a $60^\circ$ rotation corresponds to multiplication by $e^{i\pi/3}=\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}i$, so $B$ is the point $(1/2, \sqrt{3}/2)$, or the complex number $\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}i$. Finally, since $1/3$ of the perimeter is between $B$ and $(1,0)$, we have

Using similar reasoning (but a bit more complicated trigonometry and algebra), the point $D$ gives us the special value

and the point $A$ gives us the value

and, finally, point $X$ gives us

These points are fairly easy to calculate because they occupy positions on the Koch Snowflake that remain constant after the first few iterations. Points $A$ and $C$ are on the perimeter of the very first iteration (the equilateral triangle), the outermost points of the snowflake at $(1,0)$, $B$, and $D$ are present from the second iteration onward, and $X$ from the third generation onward. They also mark very natural points of division and symmetry on the snowflake, making it easy to see what proportion of its arclength they partition. But what if we wanted to calculate something like

This is where things get really interesting. We can actually also calculate $\text{kxp}(L/5)$ (and other less obvious special values, as we will see later) by making use of symmetries and self-similarities of the Koch Snowflake. Let’s begin by establishing a few functional equations of the $\text{kxp}$ function. First:

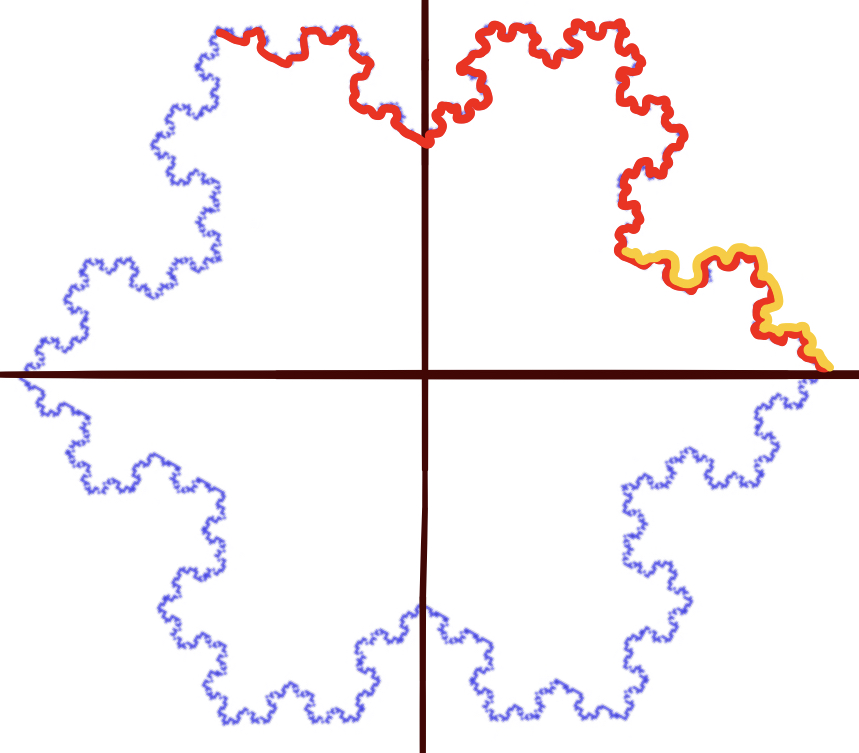

holds for $p\in (0, 2/3)$. To see why, check out this diagram:

The segment traced in red is similar to the segment traced in yellow. More specifically, the yellow segment is obtained by shrinking the red segment by a factor of $3$ and translating it $2/3$ units to the right. Using similar reasoning (I’ll omit the details), we can also obtain the following functional equations:

for $p\in (0,2/3)$; and

for $p\in (2/3,4/3)$. By plugging values of $p$ into these functional equations, we can calculate less-obvious values of $\text{kxp}$. For example, by letting $p=4/5$ in equation (iv), we have that

Now notice that $\text{kxp}(L/5)$ and $\text{kxp}(4L/5)$ will be on opposite sides of the x-axis. In other words, if $\text{kxp}(L/5)=a+bi$, then $\text{kxp}(4L/5)=-a+bi$. This means that

If we split this equation into real and imaginary parts and solve for $a$ and $b$ separately, we get $a=1/2$ and $b=\sqrt{3}/4$. This gives us the following special value:

By employing functional equations (i)-(iv) and exploiting other symmetries of the Koch Snowflake, I’ve managed to calculate many other special values of $\text{kxp}$, such as the following:

It turns out that equations (i)-(iii) allow us to calculate the position of $\text{kxp}(pL)$ pretty easily if $p$ is a rational number whose base-4 representation contains no threes. Consider, for example, $1/7$, which equals $0.\overline{021}$ in base 4. Notice that Since each of the three numbers $0.\overline{021}_4, 0.\overline{210}_4, 0.\overline{102}_4$ is less than $2/3$, we may use these three equalities in tandem with equations (i)-(iii), resulting in the equalities

We can now solve this as a system of equations in three unknowns. By eliminating all of the unknowns except $\text{kxp}(0.\overline{021}_4 L)=\text{kxp}(L/7)$, we end up with the equation

Solving this equation is trivial (although the arithmetic is a bit messy), and it yields the value stated earlier:

If you’re looking for a challenge, try one of these problems:

1) Prove that the following functional equation holds for $p\in (0,2/3)$:

2) Try calculating the value of $\text{kxp}(pL)$ for a rational value of $p$ whose base-4 representation does contain threes, like $p=1/11$ or $p=1/13$. You may have to come up with your own functional equations or exploit symmetries that we haven’t explicitly mentioned yet.