In this post, I’ll introduce the basics of Order Theory, as well as some interesting puzzles for the reader to attempt throughout. Although Order Theory in general deals with posets, or partially ordered sets, this post will only deal with total orders, since I’ve found that they alone provide more than enough food for thought for a single blog post.

If you’re already familiar with the basics of order theory, you can skip the first three sections.

We could jump right into formal definitions, but because visualization has been very helpful during my exploration of orders, I think an intuitive explanation is in order. You should already be familiar with the symbols $\le$ and $\ge$, which, in ordinary arithmetic, represent the concepts “less than” and “greater than”. In general, order theory helps formalize concepts like “big/small”, “first/last”, “earlier/later”, and “better/worse.”

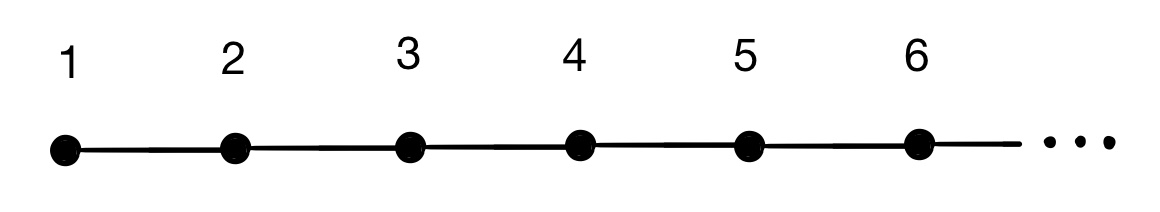

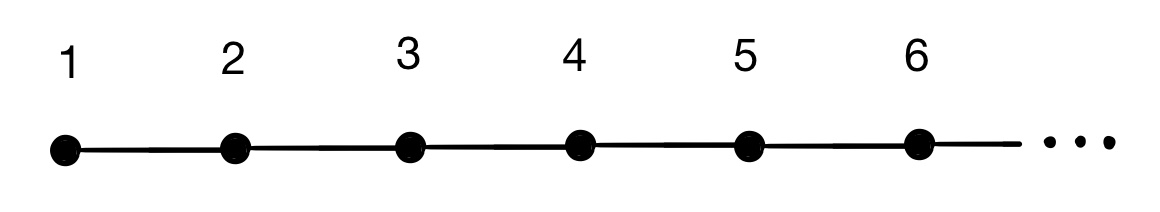

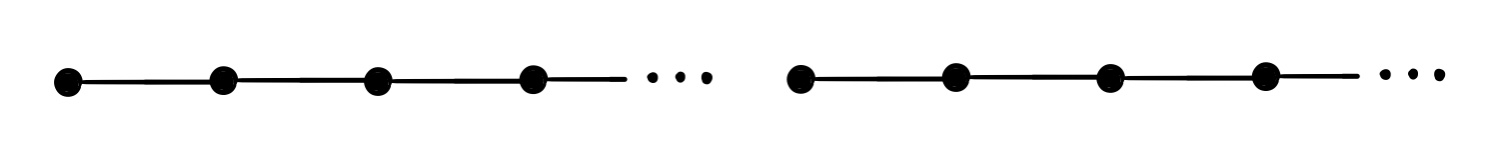

You’ve probably used $\le$, $\ge$, $\lt$, and $\gt$ to compare integers before using statements like $10\ge 7$, which expresses the idea “ten is greater than seven” or “ten is more than seven.” However, these symbols need not be restricted to natural numbers. For example, they could be used to express alphabetical order of words: $\text{apple}\space\gt \space\text{ape}$ might express the idea “the word ‘apple’ comes after the word ‘ape’ in a dictionary.” Often, we can visualize these structures using a number-line-like diagram, with “bigger” or “later” objects farther to the right and “smaller” or “earlier” objects farther to the left. For the natural numbers, we could use an ordinary number line:

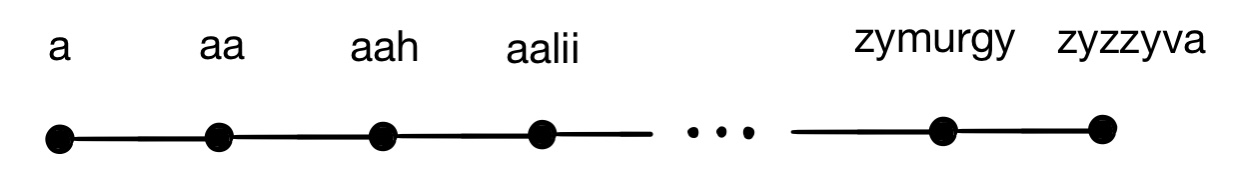

and for the words in a dictionary, we could use a similar diagram:

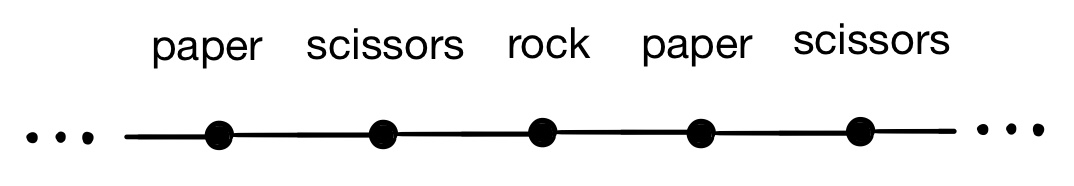

However, these comparators don’t seem appropriate for modelling certain situations. For example, suppose we wanted to use $\lt$ and $\gt$ to describe the structure of the game rock, paper, scissors, with an inequality like $\text{paper} > \text{rock}$ representing the statement “paper beats rock”. If we try to represent this using another linear diagram, it becomes apparent that this structure isn’t like the others:

The cyclic nature of rock-paper-scissors has caused our diagram to turn out a bit weird. We can’t use this to compare rock, paper, and scissors based on which is farthest to the right, because everything is to the left and right of everything else. Scissors appears two steps to the right of rock, which would appear to suggest that $\text{scissors} > \text{rock}$, but it also appears to the right of rock, which appears to suggest that $\text{scissors} < \text{rock}$. Yuck.

If we want to avoid imposing orders on inappropriate situations like this, we need some strict rules about what orders are and what they are not. The following rules define what kinds of structures the symbols $\ge$, $\le$, $\gt$, and $\lt$ can be used to describe:

Clearly, rock-paper-scissors does not obey these rules. If we treat the rock-paper-scissors comparator $\gt$ as if it were transitive, the statements $\text{scissors} >\text{paper}$ and $\text{paper} > \text{rock}$ would imply $\text{scissors} > \text{rock}$. Combined with the fact that $\text{scissors} < \text{rock}$, this would violate the first rule.

These rules still aren’t quite enough to define a total order. Here’s an example of an order satisfying the three rules above that isn’t a total order. Suppose we impose $\le$ and order on all words such that $w_1 \le w_2$ if the word $w_1$ is contained within the word $w_2$, and $w_1 < w_2$ if $w_1\le w_2$ and $w_1\ne w_2$. For example, we would have

This ordering clearly satisfies the three criteria described before: no two distinct words can be contained within each other, and “inclusion” is transitive. However, consider the following question: how would you compare the words “cat” and “dog”? Which of the two words is “greater”? Obviously, it is not the case that $\text{cat} < \text{dog}$, since “cat” is not a subword of “dog”, nor is $\text{dog} < \text{cat}$.

When dealing with natural numbers or integers, any two numbers are comparable. That is,

This extra rule is what distinguishes a total order from a partial order. A totally ordered set satisfies the above rule, but a partially ordered set does not need to satisfy this rule. Clearly, the word-containment ordering described above is only a partial order.

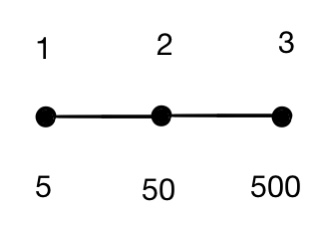

Before we get to the fun part, I should clarify that an order type and an ordered set are not the same thing. Consider the following two sets of numbers, endowed with the traditional ordering on natural numbers:

Obviously, these two sets are unequal.

However, the orders on both sets “look the same” as each other. In a very non-rigorous way, we might say that they’re equivalent in some sense because they have the same number-line diagram:

Instead of saying that these ordered sets are equal (which would be false), we may say that they are isomorphic, or that they have the same order type. Using mathematical symbols, we may express that two ordered sets $A$ and $B$ are isomorphic by writing $A\cong B$.

How can we formalize the notion of isomorphism? One way is to say that two ordered sets $A$ and $B$ are isomorphic if there exists an order-preserving bijection $f$ from $A$ to $B$. A bijection is a function $f$ that “translates” elements of $A$ into elements of $B$ such that every element of $B$ corresponds to exactly one element of $A$. The bijection is order-preserving in, for all $a_1, a_2\in A$ with $a_1<a_2$, then the “translations” $f(a_1)$ and $f(a_2)$ of $a_1$ and $a_2$ in $B$ also satisfy $f(a_1)<f(a_2)$.

For example, to show that the ordered sets ${1,2,3}$ and ${5,50,500}$ are isomorphic, we would define the function $f$ such that $f(1)=5$, $f(2)=50$, and $f(3)=500$.

The simplest order types are the finite orders, whose underlying set is finite. The example considered in the previous section was a finite order with three elements. Given any positive integer $n$, there is exactly one total order type with $n$ elements. Equivalently, all n-element totally ordered sets are isomorphic. To construct a bijective function mapping any n-element total order to another, simply map the smallest element of one order onto the smallest element of the other order, the second-smallest element onto the corresponding second-smallest element, and so on. The n-element order is sometimes denoted $[n]$, but in this post I’ll just use the numeral $n$.

There’s also the trivial order containing no elements at all (its underlying set is the empty set). This can be denoted by $\varnothing$, but we won’t really be dealing with this order (it’s trivial, after all), so don’t worry about it too much.

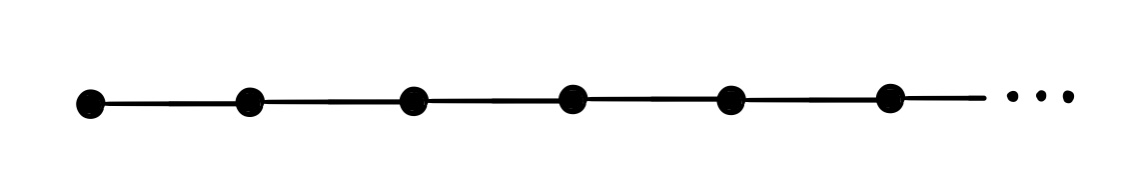

Next we have the traditional ordering on the natural numbers, denoted $\mathbb N$. Here’s a copy of the number-line diagram we used earlier to visualize its structure:

Although you’re already familiar with this structure, here are some statements we could use to more rigorously define the natural numbers in the context of order theory:

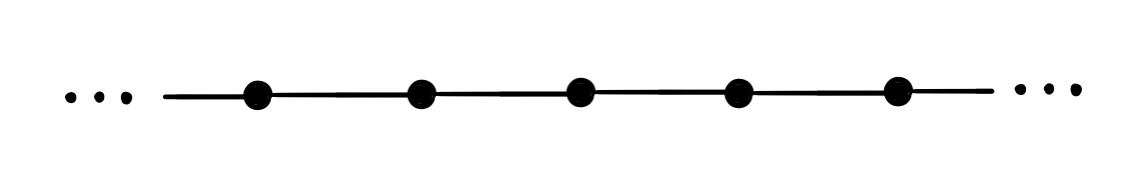

Another similar structure is that of the integers, denoted $\mathbb Z$. Here’s a number-line diagram for $\mathbb Z$:

The components of the rigorous definition of $\mathbb Z$ are very similar to those of $\mathbb N$ - the only change we need to make is to negate the first of the three statements above.

The ordinal numbers are also extremely useful for classifying order types. The ordinals encapsulate all well-ordered order types, which are defined as order types satisfying the following additional property:

The construction of the ordinal numbers is grounded in set theory. The first ordinal number, $0$, is represented by the empty set $\varnothing = {}$. The number $1$ is represented by the set containing zero, ${\varnothing} ={{}}$. The number $2$ is equated with the set containing $0$ and $1$, or ${0,1}={{},{{}}}$, and $3$ is equated with the set containing $0,1,$ and $2$, and so on. In general, all ordinal numbers have a successor, and the successorship operation is defined as

As a consequence, for any two ordinal numbers $a$ and $b$, $a\subset b\iff a\in b \lor a=b$. The comparator $a<b$ is defined so that $a<b \iff a\in b$.

Larger infinite ordinals are sets containing all of the smaller ordinals as its elements. For example, the first infinite ordinal, denoted $\omega$, is the set of all finite ordinals:

Therefore, the ordered set $\omega$ is equivalent to $\mathbb N$, or $\omega\cong\mathbb N$. The successor to $\omega$, denoted $\omega + 1$, is given by

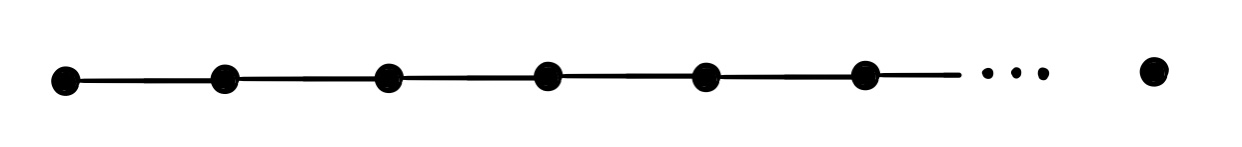

It consists of all of the natural numbers, combined with one “infinite” number that is greater than all of the naturals. The ordinal $\omega + 1$ would have the following number-line diagram:

There are also the ordinals $\omega + 2$, which is comprised of the naturals with two additional “infinite” elements, $\omega + 3$, which has three extra elements at the top, $\omega + 4$, $\omega + 5$, and so on. The set of all of these ordinals is denoted $2\omega$ (other sources often write it $\omega\cdot 2$), and it looks like two copies of $\mathbb N$, one after the other:

Then there are the ordinals $3\omega$, $4\omega$, $\omega^2$, $\omega^3$, $\omega^{500}$, $\omega^\omega$, $\omega^\omega$, and so on. I won’t discuss these extensively here, since the operations we discuss in the next section will allow us to construct compound orders like these. If you’re interested in ordinals, I encourage you to read about them outside of this post - there are some really interesting counterintuitive and mind-bending theorems about ordinals.

Finally, we have a few dense orders like $\mathbb Q$ and $\mathbb R$. A dense order is defined as an order with the additional property that

That is, for all elements of the order, there exists a third element that lies between them. This is of course true for the rationals and the reals: the arithmetic mean of any two rationals is a rational between the original two, and the mean of two reals is a real between the original two. There are lots of other dense orders, such as the dyadic rationals, defined at the rational numbers whose denominators are powers of two, or the algebraic numbers, which are the roots of polynomials with rational coefficients. We might also consider the rationals restricted to the interval $(0,1)$, or the set of rational numbers between zero and one, $\mathbb Q\cup (0,1)$, because it’s sometimes easier to work with than the entirety of the rational numbers.

However, it turns out that all of these examples are order-equivalent to each other. It happens that all countably infinite dense total orders without a least element or a greatest element are isomorphic. In other words, there is only one countably infinite dense order type with no least or greatest element. This is extremely convenient and gives rise to some nice properties, as we shall see later. We can denote this monolithic order type by $\mathbb Q$.

To prove this, we’ll need to construct an isomorphism, or an order-preserving bijection, between any two arbitrary countably infinite dense unbounded ordered sets $A$ and $B$. First of all, since they’re countably infinite, we know that there exist bijections $f_A:\mathbb N\to A$ and $f_B:\mathbb N\to B$. Therefore, given any subset of $A$ or $B$, there exists an element $x$ whose preimage in $\mathbb N$ is smallest. Call this the “priority element” of that subset. Now let’s try to define an isomorphism $f:A\to B$. We can start by picking arbitrary “anchor points” $a_0\in A$ and $b_0\in B$, defining $f(a)=b$. Now we may divide $A$ and $B$ into two subsets: $A$ is divided into the set $A_>$ of elements greater than $a$ and the set $A_<$ of those less than $A$, and $B$ is divided into $B_<$ and $B_>$, comprising the elements less than $b$ and greater less than $b$. Now, let $f$ map the “priority element” of $A_<$ onto that of $B_<$ and the “priority element” of $A_>$ onto that of $B_>$. Now $A_<,B_<,A_>,$ and $B_>$ have each been split into two more subsets of unassigned values by their respective “priority elements”, and we can repeat this process recursively. Because of the countability of $A$, for any element $a\in A$, the value of $f(a)$ will eventually be assigned this way, showing that $f$ is well-defined.

That’s it! This proof wasn’t completely rigorous, but it should suffice for our purposes.

There’s one more familiar dense order type: $\mathbb R$, the real numbers. If we were to construct a number-line diagram for $\mathbb R$, it would just be an infinitely long continuous straight line, or a finite line segment with no extremal end-points:

It’s not immediately obvious how $\mathbb R$ should be rigorously defined, since it’s continuous rather than discrete. We’ll get to this later in the next section when we discuss “exponentiation” of order types.

Now let’s define a few operations that allow us to modify and combine the orders we’re already familiar with, vastly expanding our current repertoire.

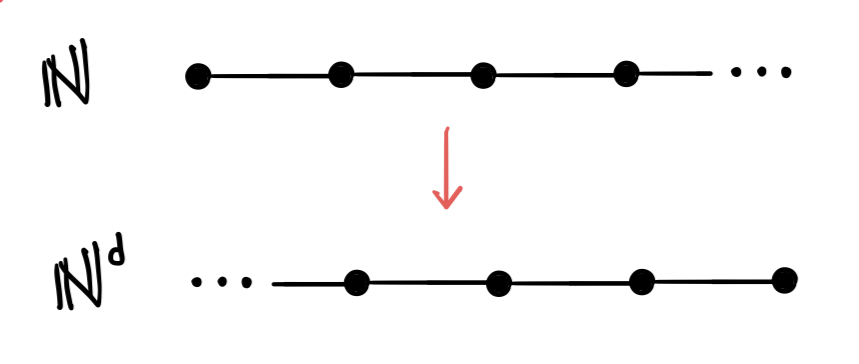

One simple example is the dual operator, which basically just flips an order backwards. If $A$ is an order, then its dual order is denoted $A^d$. For example, here’s what we get when we apply the dual operator to $\mathbb N$, forming $\mathbb N^d$:

We can define the dual operator more rigorously be saying that $B\cong A^d$ if and only if there exists an order-reversing bijection $f:A\to B$, such that $a_1 < a_2$ implies $f(a_1) > f(a_2)$.

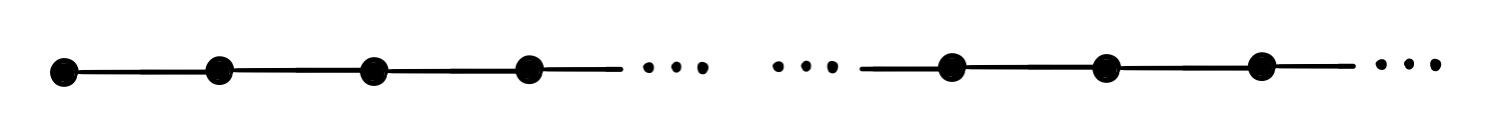

Remember how we noted earlier that $2\omega$ looks like two consecutive copies of $\mathbb N$? Now let’s generalize the notion of “stringing together” or “concatenating” one or more different orders to form compound orders. The order formed by concatenating the orders $A$ and $B$ (in that order) will be denoted $A+B$. For example, $\mathbb N + \mathbb Z$ would look like this:

More explicitly, $A+B$ is the set consisting of the elements of $A$ and the elements of $B$, such that all elements of $B$ are greater than $A$, or all elements of $B$ “come after” the elements of $A$. Watch out: this “addition” operation is not commutative, since $A+B$ is not necessarily isomorphic to $B+A$. However, it is associative; that is, $A+(B+C)=(A+B)+C$ for any three orders $A,B,C$. It also has the following relationship with the dual operator:

Some of the order types we’ve learned about already can be related to each other using this “concatenation” operator. For example, $2\omega \cong \mathbb N +\mathbb N$, and $\mathbb Z\cong \mathbb N^d +\mathbb N$. Each of the following equivalences are also true - can you figure out why?

Now that we’ve come up with an “addition-like” operation for orders, we might next try to devise something similar to multiplication. As it turns out, there is a natural analogue of multiplication to order types. If we wanted to construct an order type consisting of exactly $500$ copies of $\mathbb N$ concatenated to each other, it might get tiresome to write out the $499$ addition signs necessary to express this order using the concatenation operation:

Instead of this, we might write $500\cdot \mathbb N$, or $500\mathbb N$. But what about an order consisting of infinitely many copies of $\mathbb N$, like this:

Analogously, we could denote this by $\mathbb N\cdot\mathbb N$. We could also have copies of $\mathbb N$ stretching infinitely in both directions, in which case we would have the order $\mathbb Z\cdot \mathbb N$. In general, the order $A\cdot B$ can be formed by replacing every individual element of $A$ with a miniature copy of $B$. Rigorously, the ordered set $A\cdot B$ can be constructed from $A$ and $B$ by using $A\times B$, or the Cartesian product of $A$ and $B$, as the underlying set, and defining the order as follows: $(a_1,b_1)<(a_2,b_2)$ if $a_1 < a_2$, or if $a_1 = a_2$ and $b_1 < b_2$. In other words, two pairs of elements are compared by comparing the first element in each pair, and the second elements are used as a “tiebreaker” should the first entries be equal.

Once again, despite the fact that traditional multiplication is commutative, this operation is not commutative: it is not necessarily the case that $A\cdot B\cong B\cdot A$. Like concatenation, however, it is associative, and $A\cdot (B\cdot C)\cong (A\cdot B)\cdot C$. It also satisfies a partial form of distributivity over the “addition” we defined earlier:

However, it is not the true that $A\cdot (B+C)\cong A\cdot B + A\cdot C$ in all cases, so distributivity only works in one direction. The dual operator also distributes over this type of multiplication, so that $(A\cdot B)^d\cong A^d\cdot B^d$.

Here are some equivalences involving “multiplication.” See if you can figure out why they are true.

Finally, now that we’ve defined a special kind of “addition” and “multiplication” on orders, it’s only natural to look for an extension of exponentiation. Given two orders $A$ and $B$, can we intuitively define an order corresponding to the notation $A^B$?

Multiplication allows us to define orders like $\mathbb N\cdot \mathbb N$, $\mathbb N\cdot \mathbb N\cdot\mathbb N$, and so on. For brevity’s sake, we might use exponential notation to express (finitely) repeated multiplication such that these two examples are written $\mathbb N^2$ and $\mathbb N^3$ respectively. We can use this notation to express deeply nested orders that would be tedious to write out using repeated multiplication, such as $\mathbb N^{99}$. In general, $\mathbb N^n$ can be represented as a set of lists of $n$ natural numbers, compared “lexicographically” by first comparing the first number in each list, then reverting to the second number in the case of a tie, and then to the third number in the case of another tie, and so on. Given these interpretations for $\mathbb N^n$, can we intuitively define an order corresponding to $\mathbb N^\mathbb N$ or $\mathbb N^\mathbb Z$?

Well, if $\mathbb N^3$ can be represented as a set of ordered triples $(a,b,c)$, and $\mathbb N^4$ as a set of ordered quadruples $(a,b,c,d)$, and $\mathbb N^n$ as a set of ordered n-tuples, then perhaps $\mathbb N^\mathbb N$ can be represented as a set of infinite sequences

Two sequences of this form can be compared in the same way by using the rightmost elements as successive “tiebreakers.” For example, we would have

Because these two sequences agree elementwise up until the fourth character, at which point $1<2$ and the leftmost sequence is therefore less than the rightmost sequence.

Maybe we can use the same method to define $\mathbb N^\mathbb Z$ as an ordered set of infinite “bidirectional” sequences of the form

However, consider the following question: which of the following two elements of such a set would be greater?

We have a problem, because there is no leftmost entry at which these two elements differ from each other (since each “bidirectional sequence” stretches infinitely far to the left). This means that we have two elements that are incomparable, and this ordering scheme doesn’t give us a total order at all!

More generally, $A^B$ can only be defined this way if $B$ is well-ordered, i.e. if it is isomorphic to an ordinal. This guarantees that any two elements of $A^B$ will be comparable, because it ensures that any two “sequences” will always have a leftmost entry at which they differ, which can be used to compare the two elements.

Now let’s make a more rigorous definition of $A^B$. The order $A^B$ is defined if and only if $B$ is well-ordered, and the underlying set is populated by all functions mapping $A$ to $B$. Two distinct functions $f$ and $g$ are compared as follows: if $a\in A$ is the least element of $a$ for which $f(a)\ne g(a)$, then $f < g$ if and only if $f(a) < g(a)$ and $f > g$ if and only if $f(a) > g(a)$.

Under this definition, exponentiation satisfies some nice properties like $A^{B}\cdot A^{C}\cong A^{B+C}$, and $(A^B)^C\cong A^{C\cdot B}$. Exponentiation also allows us to rigorously define the real numbers in a way that wasn’t obvious before. I won’t prove it here, but it can be shown that the order structure of the nonnegative real numbers is isomorphic to $\mathbb N^\mathbb N$.

Since this post is already way too long, I’ll try to make this section quick, and any reader interested in embeddings can continue looking into them independently.

Intuitively, we say that an order $A$ is embeddable in another order $B$ if $B$ “contains a copy” of $A$. Formally, $A$ is embeddable in $B$ if and only if there exists an injective order-preserving function $f:A\to B$ - that is, a function mapping each element of $A$ to a unique element of $B$ such that

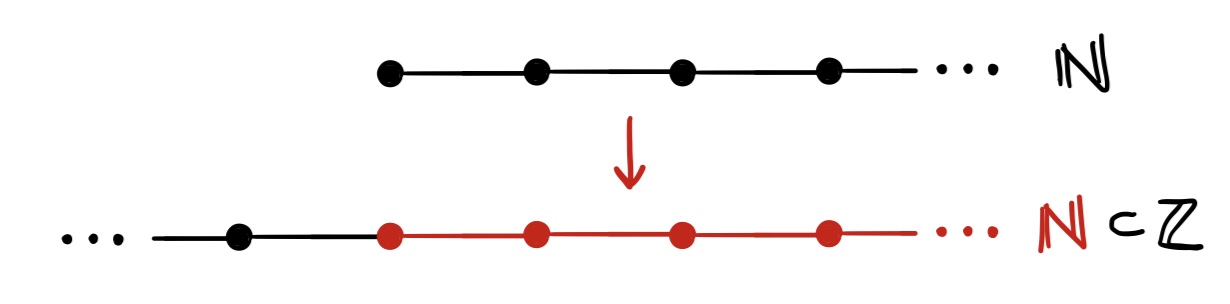

For example, $\mathbb N$ is embeddable in $\mathbb Z$ because the function $f:\mathbb N\to\mathbb Z$ defined by $f(n)=n$ is both injective and order-preserving. It’s easy to intuit that $\mathbb N$ is embeddable in $\mathbb Z$ by looking at the diagrams for $\mathbb N$ and $\mathbb Z$:

This is an obvious example of an embedding. Another obvious property of embeddings is that any order is embeddable in itself, or embeddable in itself plus some other order. However, not all questions we can ask about embedding are totally trivial - I’ll leave you with the following embedding puzzles to ruminate on:

- Is $\mathbb Q\cdot \mathbb R$ embeddable in $\mathbb R$? Is $\mathbb R^2$ embeddable in $\mathbb R$?

- Is $\mathbb N^d$ embeddable in any ordinal? If so, what is the smallest ordinal containing $\mathbb N^d$?

- Are all ordinals embeddable in $\mathbb Q$? If not, what is the smallest ordinal that is not embeddable in $\mathbb Q$?

- Are all ordinals embeddable in $\mathbb R$?

- If $A$ is embeddable in $B$ and $B$ is embeddable in $A$, is it necessarily true that $A\cong B$? If not, give a counterexample.

- Do there exist two total orders $A$ and $B$ such that $A$ is not embeddable in $B$ and $B$ is not embeddable in $A$? What about three total orders $A,B,C$ such that none of the three is embeddable in any other?

I find it interesting to apply the conceptual framework of order theory to philosophy, because ordered structures and hierarchies appear in the theories of various philosophers.

For example, in his Metaphysics, Aristotle considers the chain of causation that culminates in the occurrence of an event. Consider the event of me pressing a key on my keyboard. We can identify a thought in my mind as a cause of that event, and the cause of the thought in my brain can be identified and some pattern of electrical impulses, and so on. To formalize this chain of causation, we might let $E_0$ represent the pressing of a key on my keyboard, $E_1$ represent the thought in my mind, $E_2$ represent the pattern of neuron firings, $E_3$ the cause of those neuronal firings, and so on. And we might symbolically represent the assertion “$A$ is causally prior to $B$” by writing $A < B$. Then our chain of causality can be expressed as an order:

$$...