During high school, I refused to use social media or messaging apps because they seemed very conducive to time-wasting, mindless scrolling, and certain other bad habits. (Although, had I wanted to participate in social media, my parents probably wouldn’t have allowed it anyways.) Now that I’m in college and COVID-19 has struck, I have no in-person classes and my face-to-face interaction with other people is severely limited, so I’ve had to reevaluate my self-imposed technology restrictions. I still don’t see myself using Facebook, Instagram, or Snapchat (yuck!) anytime in the forseeable future, but I’ve started using Discord, a messaging platform intended primarily for gamers but currently used by all sorts of people. So far, my dorm and several of my classes have created chat groups on Discord through which to study, ask for help, or just hang out.

One interesting feature of Discord is that it’s very developer-friendly, and it supports the use of bots to perform automated tasks or housekeeping on servers. For example, I’ve seen bots that do things such as manage permissions of users on the server, post news articles or announcements from a feed, play music, or automatically kick or ban members. (One Christian server that I’ve seen uses a bot that automatically bans members if they use a devil emoji in their message!)

However, a bot doesn’t necessarily have to perform some task beneficial to the server - it can also scrape data from the server to analyze and use elsewhere. In particular, if a Discord bot is given adequate permissions by server admins, it can access the server’s entire message history! For active servers that have been running for months or even years, this is a huge amount of data that is ripe for the taking and which could be useful for, say, developing mathematical/statistical models that could be used for natural language processing.

In this post, I’ll show how to use Discord.py to scrape messages from a server, and then use the Markov model of natural language (as implemented by a very handy Python library called markovify) to randomly generate novel messages which imitate users’ previous messages on the server. A few months ago I joined a fun server full of shameless philosophy fanatics whose messages will serve as fodder for our analysis. The result is a bot that spouts random pieces of pseudo-philosophical “wisdom” on demand - hilarity ensues!

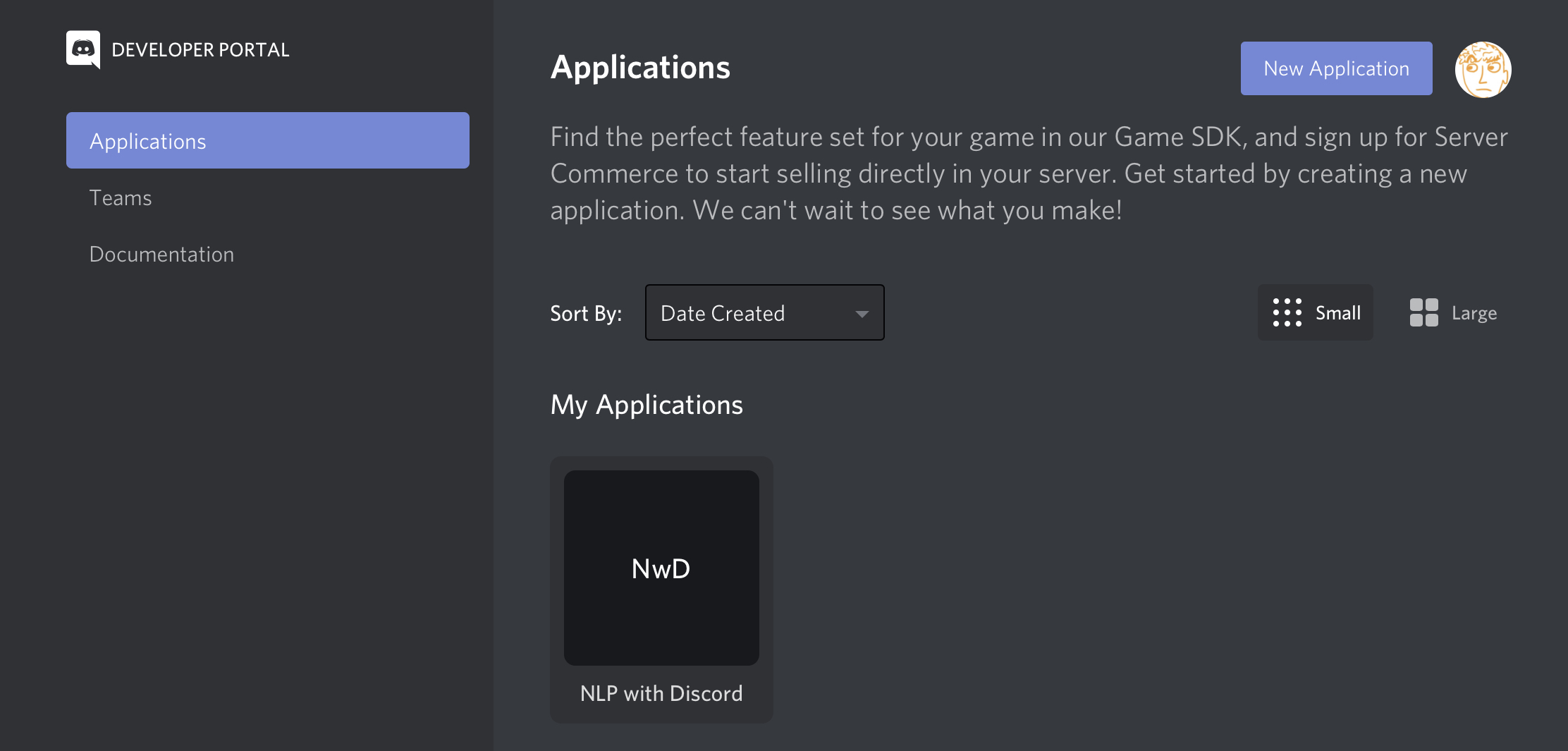

To start creating your own Discord bot, the first thing you need to do is visit the Discord developer portal, which looks something like this:

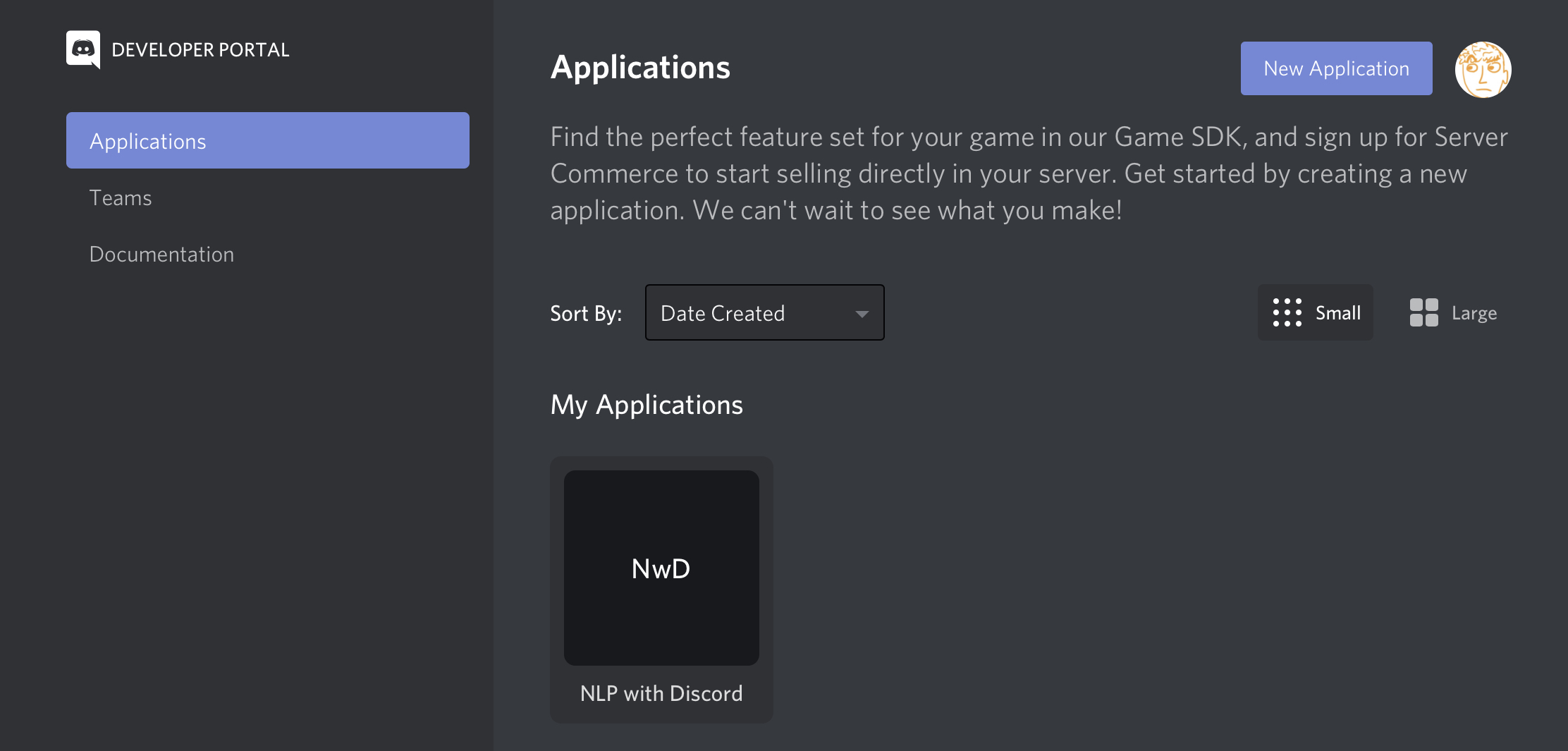

Once you’re there, create a new application, and inside the application you can create a bot. The bot design page looks like this:

See the “copy” button below where it says “TOKEN”? That will copy the unique token which identifies our bot, which we’ll use shortly to allow our Python script to log in as the bot. Keep this handy.

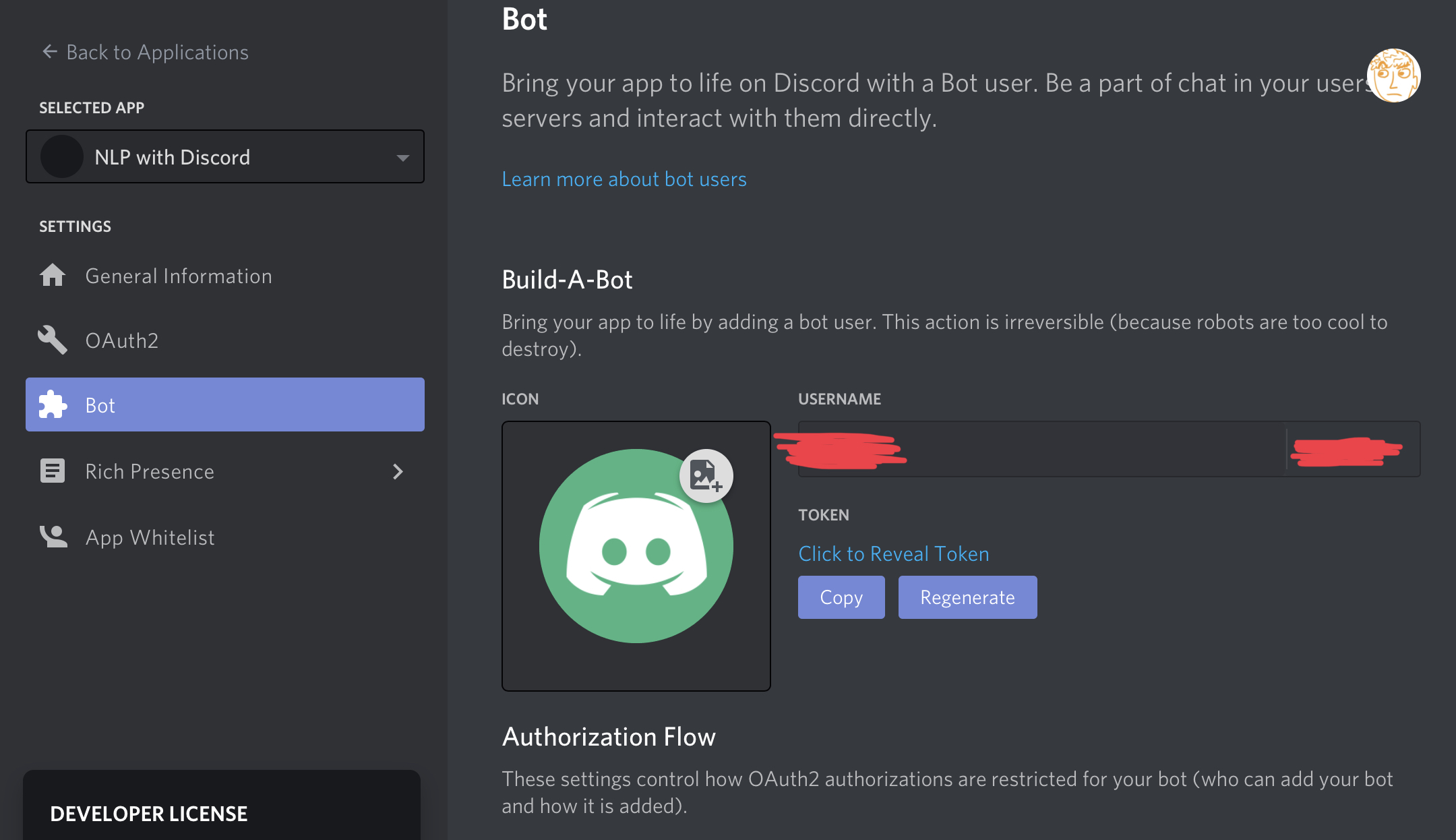

Depending on what you want to do with your bot, you may need to play with the settings a little bit. For example, if the bot is just for your own personal use or experimentation, you probably want to turn off the “public bot” feature. Also, there’s a panel of checkboxes at the bottom of the bot settings page that allows you to describe what your bot should be allowed to do on the server. Our bot just needs to be able to read and write messages, but you can change this if you want to make something more complicated:

Now let’s get to the actual code! Here’s the code for a dinky little test bot:

import discord

from discord.ext import commands

import sys

import requests

description = "Just a humble sample bot. Aims to please."

intents = discord.Intents.default()

intents.members = True

bot = commands.Bot(command_prefix='$', description=description, intents=intents)

@bot.event

async def on_ready():

print('~~ Logged in ~~')

@bot.command()

async def parrot(ctx, repeat: int, message="squawk!"):

for i in range(0, repeat):

await ctx.send(message)

@bot.command()

async def wikipedia(ctx):

r = requests.get("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/special:random")

await ctx.send(r.url)

bot.run(sys.argv[1])

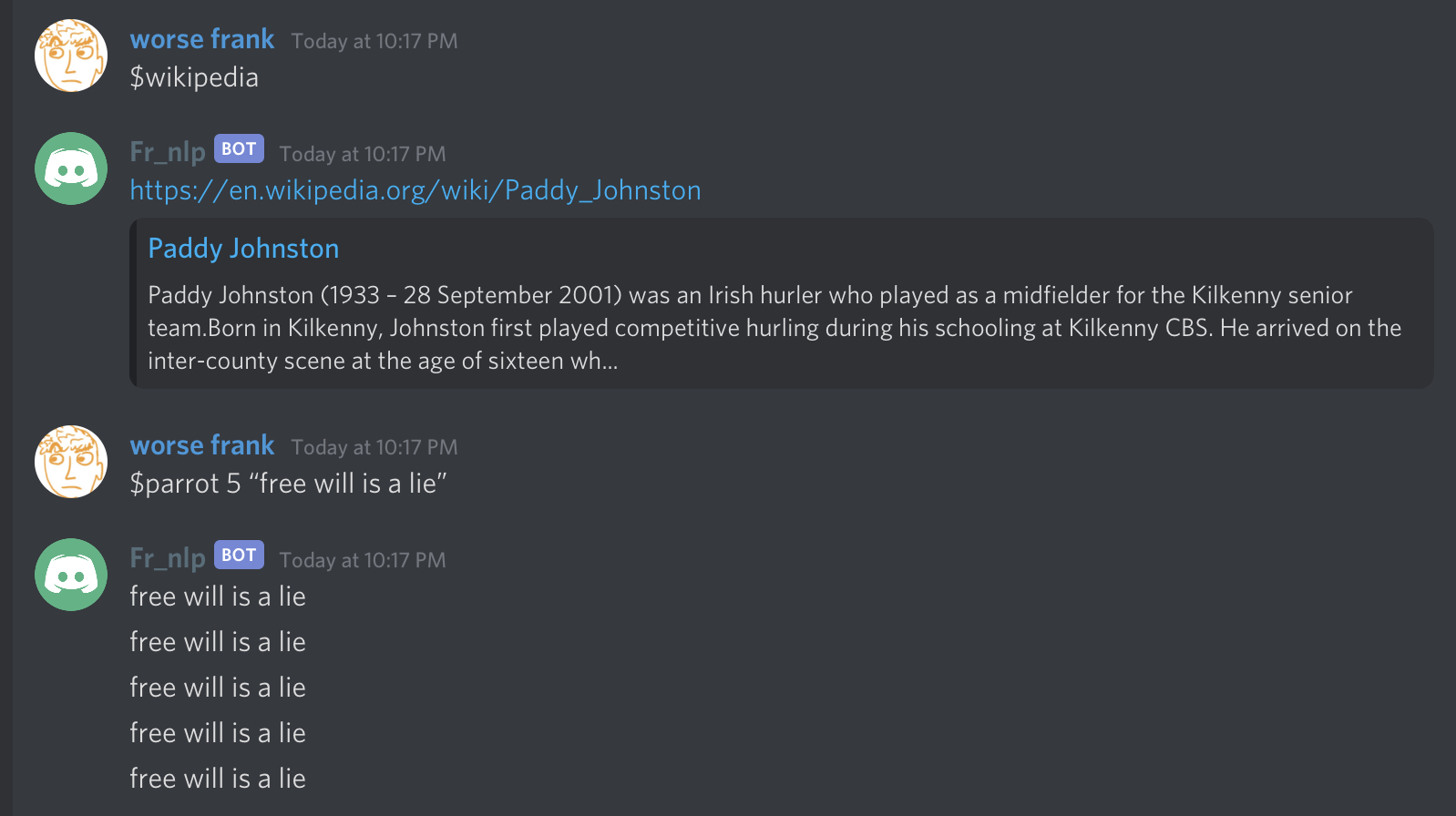

This code can also be found on Github. It should be pretty easy to figure out how this code works just by reading through it. The command $parrot x y, where x is an integer and y is a quote-enclosed string, will repeatedly send the message y a total of x times. (This has high potential for abuse, watch out!) The other command $wikipedia gets a random Wikipedia page and sends the link into the chat.

To get this bot up and running, we’ll need our top-secret bot token from earlier. From the command line, execute the following:

python3 discord_samplebot.py ‘INSERT_YOUR_TOKEN_HERE’

If the message ~~ Logged in ~~ shows up in your console a few seconds later, you’re good to go!

Now, here’s what it looks like to execute bot commands from the Discord app by sending $-prefixed messages into the chat:

Perfect! We’d like our bot to be able to do something a little more interesting than just repeat our own messages back to us, though.

The Markov model of natural language treats language probabilistically, assuming that the sequence of words in a sentence (or letters in a word) takes the form of a Markov chain. That is, it assumes that, given all of the words up to a certain point in a sentence, the next word is chosen randomly, but the probability that a word will be chosen as the next word depends on the words immediately preceding it.

In this case, we’ll be dealing with a Hidden Markov model because we don’t know the statistical frequencies with which each English word follows another sequence of English words, but we can estimate these frequencies if we are given a body of text, or a corpus, to analyze. For example, suppose we have the following corpus of English text (yes, I know, it’s far too small to draw any conclusions, but this is just a toy example):

The cat sat on the mat.

The cat ate the cake.

A cat sat on the mat.

A cat ate a cake.

The boy sat on the chair.

The boy ate the cake.

The boy jumped up and down.

A boy jumped up and down.

Of these $8$ example sentences, $5$ of them start with the word The, so our Markov model would estimate the probability of a sentence starting with the word The as $5/8$. To generate a random sentence imitating the style of this corpus, we would therefore randomly choose to start the sentence with either The or A, choosing the former with probability $5/8$ and the latter with probability $3/8$. Suppose we randomly choose to start our sentence with The. Now, looking at the above sentences again, we see that $5$ of them contain the word The (with a capital T), and in $2$ of these sentences, it is followed by cat, whereas in the other $3$, it is followed by boy. Thus, to generate the next word in our sentence, we choose cat with probability $2/5$ and boy with probability $2/5$.

Suppose we choose boy: we now see that boy appears in $4$ sentences, and that it can be followed by sat, ate, or jumped (with respective probabilities $1/4$, $1/4$, and $1/2$). And we continue in the same manner from here. Notice that this process is actually capable of generating novel sentences, such as the following:

The boy sat on the mat.

The boy ate a cake.

The cat sat on the chair.

(If you want a quick exercise, try calculating the probabilities of each of these sentences being produced.)

In the above example, the probability of each word being chosen as the next word was determined only by the previous word. However, this was only a first-order Markov model, and we could alternatively create a second-order Markov model in which the probability of each word being chosen is determined by the previous two words chosen (i.e., the probability of z being chosen to follow the previous two words x y equals the frequency with which it follows the words x y in the corpus of text). We could even create a third-order, fourth-order, or even higher order model which would imitate the patterns of words in the corpus more and more closely.

As we shall see momentarily, higher-order models have some important caveats. For one, while they will imitate the grammar of the corpus more closely and consequently avoid grammatical mistakes more effectively, they are less “creative” (i.e. less likely to produce interesting new sentences or combinations of words that are substantially different from preexisting ones in the corpus). Also, a higher-order model requires a much larger corpus - there are many more possible three- or four-word combinations than there are two-word combinations, and each combination must appear at least once somewhere in the corpus in order for our process to be able to probabilistically choose a subsequent word. The process actually fails much more often for higher-order models (when the corpus is too small), because it ends up generating a novel combination of three or four words that doesn’t appear anywhere in the corpus, so it can’t find any possible candidates for a next word.

Let’s see a quick example with a real corpus. I’ve downloaded the full text of Karl Marx’s “The Communist Manifesto” from Project Gutenberg and processed a little bit to make it easier for my Python script to swallow (e.g. by removing metainformation and putting each sentence on its own line, using a few handy shortcuts in vim). Here’s a simple Python script that uses the library markovify to generate a Markov model for the text and print a random sentence:

import markovify

import sys

f = open('corpus/marx.txt', 'r')

TEXT_MODEL = markovify.Text(f, state_size=int(sys.argv[1]))

for i in range(5):

print(TEXT_MODEL.make_sentence(tries=100))

The state_size argument specifies “how far back” the model should look when choosing a random next word, and the tries argument of the make_sentence function specifies how many times the process should retry if it fails (due to the generation of a combination of words that does not appear in the corpus). First, let’s try a first-order Markov model by running the command

python3 markov_test.py 1

And we get the following five sample sentences:

The bourgeois has got the proletariat.

For the same character, into the gradual, spontaneous class-organisation of the bourgeoisie.

The abolition of history, we have taken, one hand, has torn asunder, and crusades.

National differences and has conjured out into a social and that literature that there the petty Philistine to them on an immediately begin.

And the towns.

They’re certainly incoherent and grammatically problematic, but they have the same “feel” as the original text! Now let’s try one with a state size of $2$ and see if it sounds any better:

python3 markov_test.py 2

This gives us

This organisation of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of the proletariat are equally inevitable.

The various interests and conditions that were quite different, and that leaves no surplus wherewith to command the labour of others.

The average price of a vast association of the population over the country.

They, therefore, endeavour, and that leaves no surplus wherewith to command the labour of men superseded by that of the bourgeoisie and proletariat, in order that, after the bitter pills of floggings and bullets with which the bourgeoisie itself may immediately begin.

But does wage-labour create any property for the union and agreement of the previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed.

These definitely have grammatical problems too, but upon first glance, it’s unclear whether some of them are grammatically incorrect or whether they’re just difficult to read. In general, the Markov model isn’t great for producing grammatically correct sentences, because the grammar of English sentences are better represented using a tree structure (see this old blog post of mine) than a linear structure. But let’s try a third-order process and see if it’s any better:

No sooner is the exploitation of children by their parents?

The essential condition for the free development of each is the condition for capital is wage-labour.

The other classes decay and finally disappear in the face of division of labour increases, in the same way in which a foreign language is appropriated, namely, by translation.

It has agglomerated production, and has concentrated property in a few hands; overproduction and crises; it pointed out the inevitable ruin of the contending classes.

But with the development of the conditions of your bourgeois notions of freedom, culture, law, etc.

This is not much better, probably because of the inherent limitations of the Markov model. Just for giggles, let’s try a fifth-order model:

Since the development of class antagonism keeps even pace with the dissolution of the old conditions of existence.

None

Capital is a collective product, and only by the united action of all members of society, personal property is not thereby transformed into social property.

None

None

As I mentioned earlier, higher-order models fail pretty often when the corpus is small (and Marx’s “The Communist Manifesto” isn’t very long), hence the failure of $3$ out of $5$ of our attempts to generate sentences. From now on, we’ll stick with first- and second-order models.

Let’s start by allowing our bot to imitate Marx (or any other philosopher for whom we can find a plaintext corpus to analyze), and from there we’ll move on to making a bot that writes messages imitating the actual denizens on a server. We’ll use our rudimentary sample bot as a starting point, and we actually just have to add a few lines to turn a squawking parrot into a full-on Marxist. (The code is on Github if you want to see it in its final form.)

First, we need to add a line at the beginning importing markovify:

import markovify

Next, also at the beginning of the file, we add the following lines to generate a Markov model for marx.txt (i.e. my preprocessed version of The Communist Manifesto) as well as every other text file stored in a folder labelled corpus, keeping each Markov model separate:

bot.TEXT_MODELS = {}

texts = os.listdir('corpus/')

for t in texts:

f = open('corpus/' + t, 'r')

bot.TEXT_MODELS[t] = markovify.Text(f, state_size=2)

Finally, we just need to write a command that prompts our bot to offer some wisdom in the Discord chat, in the style of a specified philosopher:

@bot.command()

async def imitate(ctx, person):

if person + '.txt' in bot.TEXT_MODELS:

await ctx.send(bot.TEXT_MODELS[person + '.txt'].make_sentence(tries=100)

else:

await("Sorry, I don't know anyone by that name.")

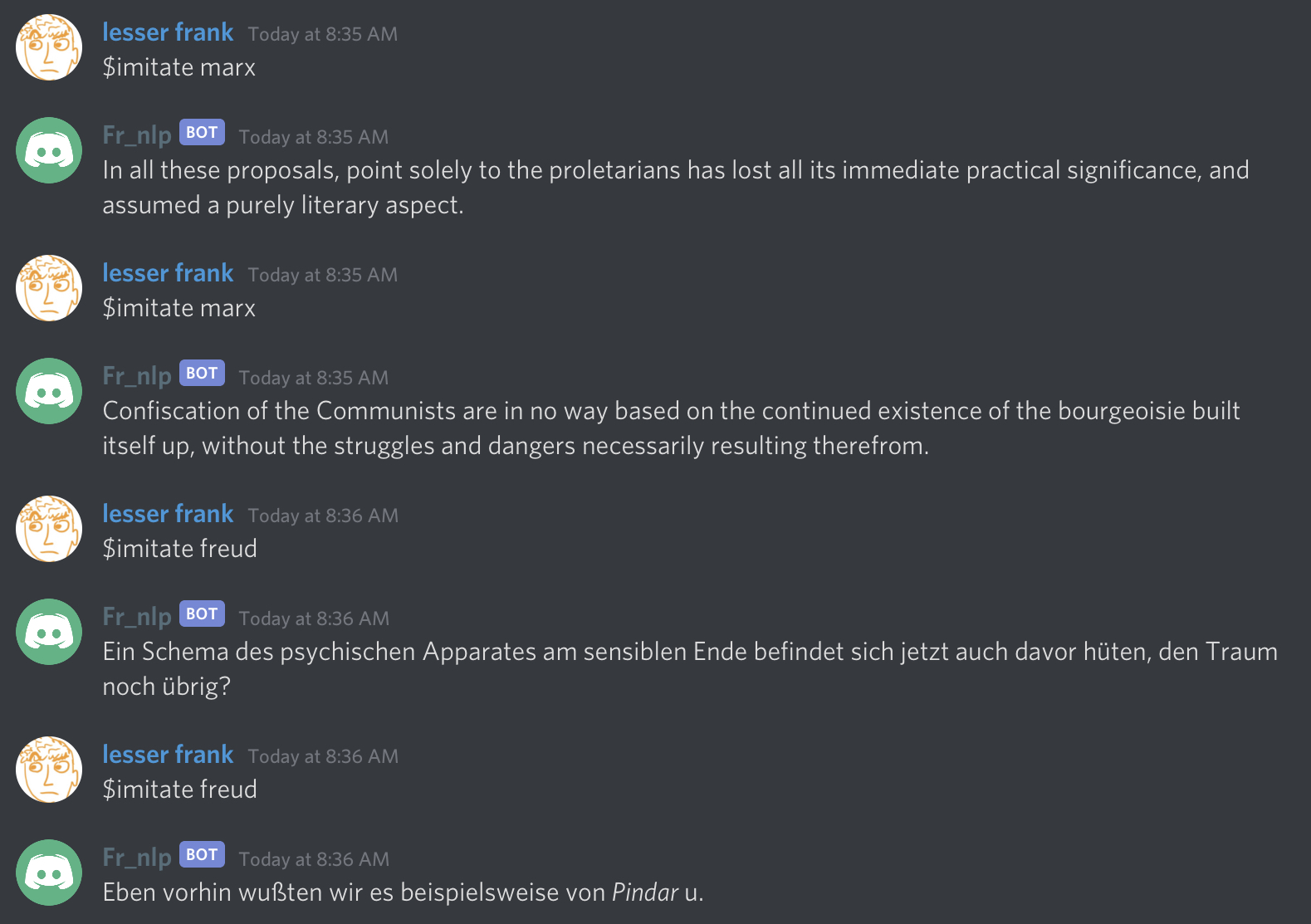

Right now, this will only work if marx is passed in as the value of the argument person, since the only file in our corpus is marx.txt. Just so we can test out this command with a different argument, I’ve added another file in the corpus folder called freud.txt (which contains the full text of Freud’s “The Interpretation of Dreams” - in German, no less). Now let’s run our bot script and test this command out in the chat:

It works like a charm! Now for the really interesting part - scraping message from the server and imitating them.

First of all, when we’re scraping messages, we probably don’t want to process all of the messages. Things like embedded links or emojis might confuse the Markov model, so we only want to grab messages that contain normal words and sentences (and punctuation, of course). We can accomplish this using Regular Expressions. First, we must import the Regex module for Python:

import re

and then we can write a Regular Expression to match only texts that include alphanumeric characters, numbers, and common punctuation marks:

bot.RE_MESSAGE_MATCH = '^[a-zA-Z0-9\s\.,“”!\?/\(\)]+$'

We’ll use this later when we scrape messages. Honestly, this will probably exclude some messages that could potentially be used in the Markov model, but this shouldn’t be a big deal, since we have more than enough data (people have been messaging each other on this server almost every day for months).

Now let’s write a command that scrapes the last, say, $5000$ messages from a channel and incorporates them into a Markov model. Here’s the code up front, and I’ll comment on a few lines to explain what’s happening here:

@bot.command()

async def scrape(ctx):

working_history = await ctx.channel.history(limit=5000).flatten()

fulltext = ''

for m in working_history:

if re.match(bot.RE_MESSAGE_MATCH, m.content) and not m.author == bot.user:

fulltext += m.content + '\n'

bot.TEXT_MODELS['you'] = markovify.NewlineText(fulltext, state_size=2)

await ctx.send("Markov model generated successfully!")

Now some comments:

ctx is the “context” of the command, from which we can determine the channel into which the command was sent. We haven’t had to use this in any of our previous commands, but it is passed to every function as an implicit argument..flatten() converts the “history” object into an array filled with “message” objects.if statement, the not m.author == bot.user part ensures that the bot will ignore its own messages, so that it only analyzes messages coming from (presumably) real humans.RE_MESSAGE_MATCH string that we designed earlier to exclude messages that aren’t plain text.for loop concatenates all of the messages into a single enormous string in which the messages are separated by newlines, and the markovify.NewlineText function can be used to parse this string and create a Markov model from it.Now all we have to do is make a command that generates and sends a random sentence, but this is the easy part:

@bot.command()

async def mock(ctx):

imitation = bot.TEXT_MODELS['you'].make_sentence(tries=100)

if imitation:

await ctx.send(imitation)

else:

await ctx.send('Sorry, something went wrong.')

Now the fun begins!

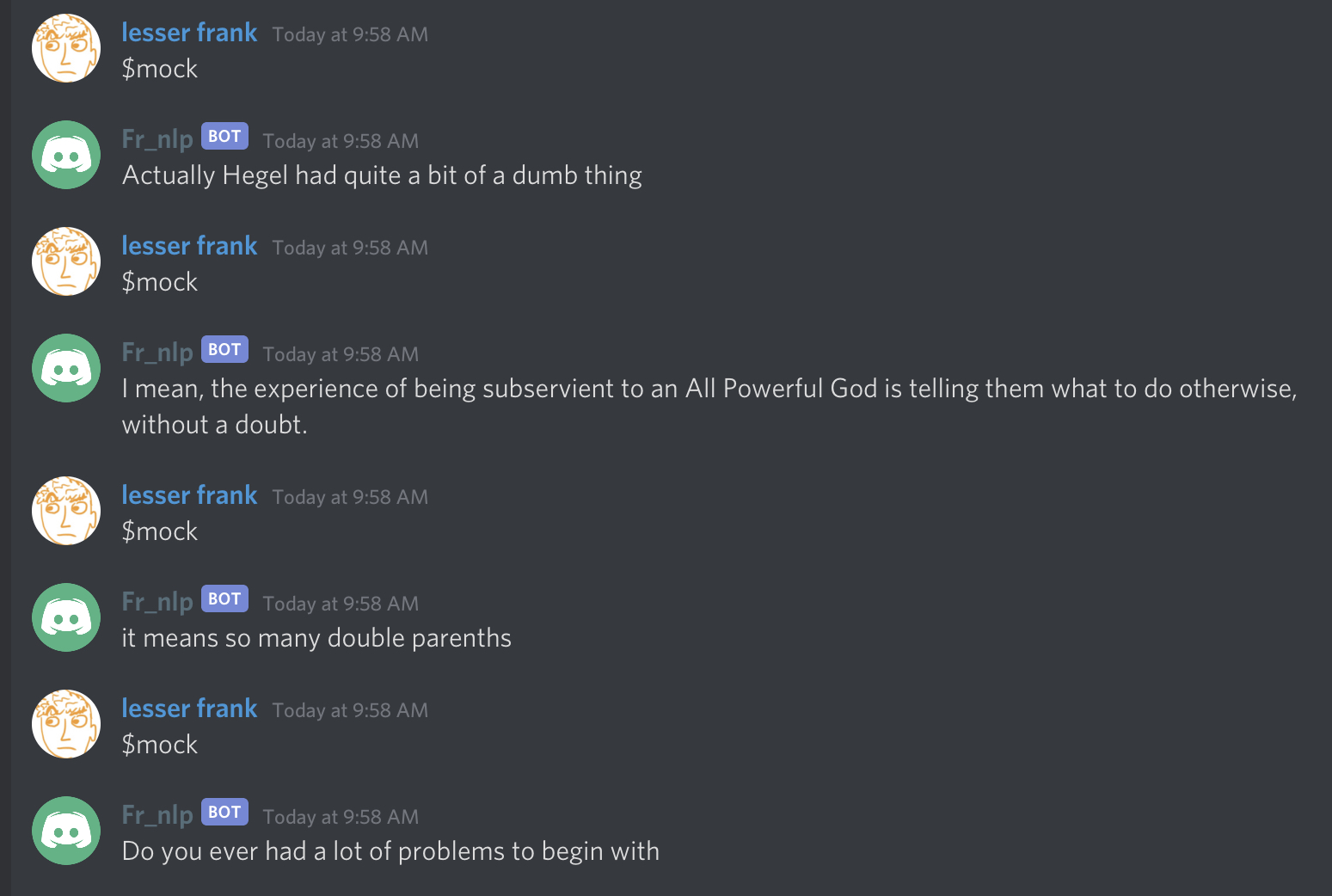

Here’s the result of some preliminary testing of our bot:

Of course, before doing this, I had to run the command $scrape in the server’s main discussion channel in order to collect conversation data for the bot to imitate. As with our imitations of Marx and Freud, we occasionally get a message that makes a bit of sense, but usually we get some kind of grammatically dubious gibberish that vaguely resembles a meaningful statement.

This bot, however, is a bit different: rather than imitating sentences from an actual published book, it’s imitating people’s casual messages to each other on a philosophy hangout server. This means that it copies not only our words, but also our common abbreviations (such as tbh, imho and lol) and even typos (such as somethign in the place of something).

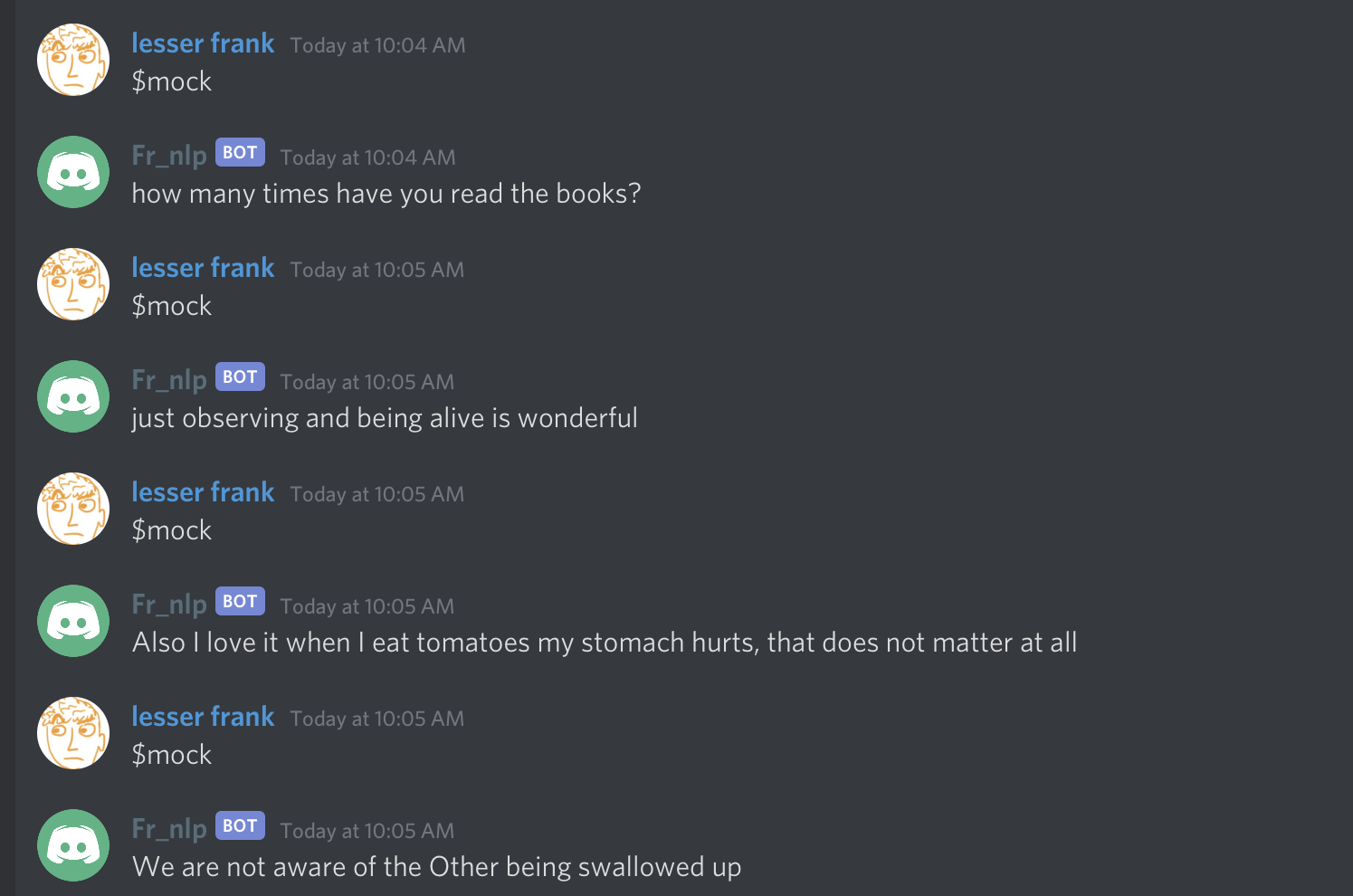

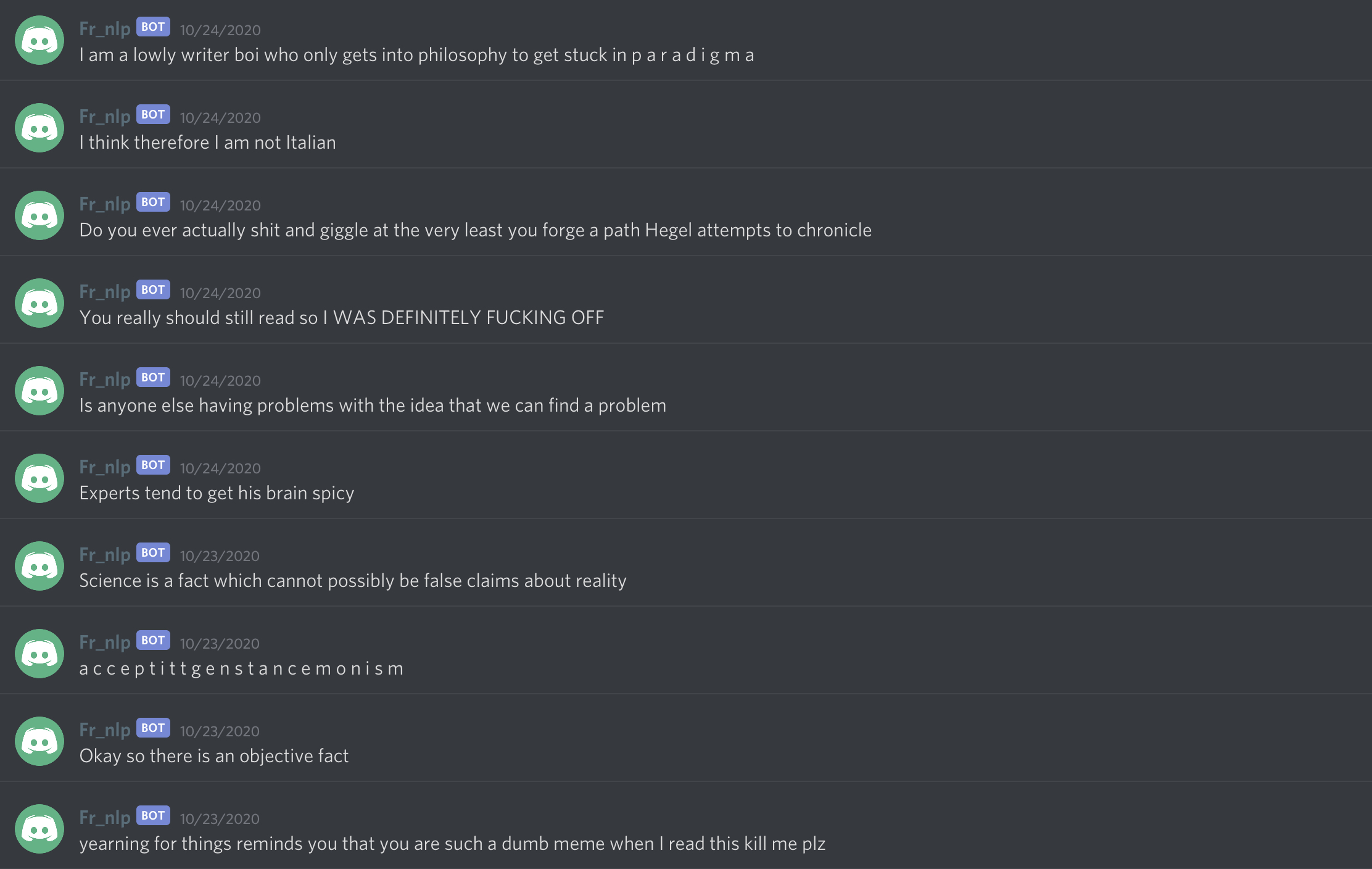

Here are some more examples:

I’ll conclude this post with a “best-of” list of everyone’s favorite pieces of wisdom from our resident robo-philosopher:

I would speculate that part of what makes these message so funny is that this server contains both philosophical discussions and silly memeing and goofing off - and the bot, unable to distinguish between the two, often juxtaposes them. ”I think therefore I am not Italian” and the message about “shitting and giggling” about Hegel are two perfect examples.