A complex power series is an infinite series of the form

where the coefficients $a_n$ are complex numbers, and $z$ is an arbitrary complex number. In previous posts that have dealt with infinite series, my main concern has been determining closed-form expressions for their exact value. In this post, I’ll instead consider the convergence of infinite series of the above form.

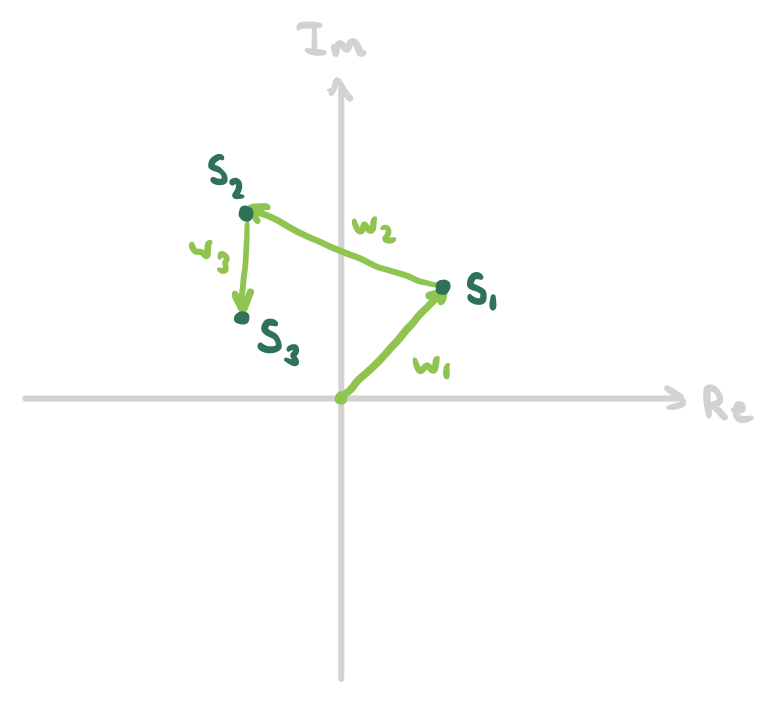

Whereas the partial sums of an infinite series of real numbers are constrained to bounce back and forth along the 1-dimensional real line, the complex numbers are represented graphically in a 2-dimensional plane, allowing for a much richer geometrical interpretation. Given a sequence of complex numbers $w_n$ and the partial sums of its series

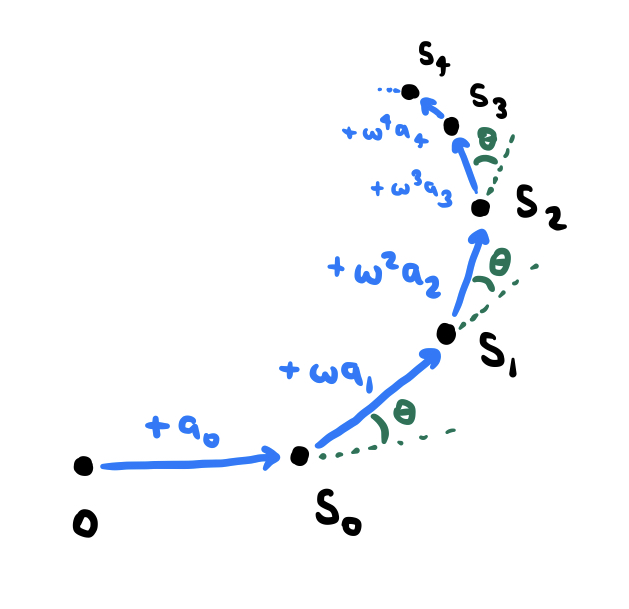

we may represent them in the plane, say, as follows:

The simple fact that the arithmetic of complex numbers involves two dimensions instead of one makes issues of convergence much more interesting.

One natural question to ask about complex power series is "for what values of $z$ does the series converge?" Or, if we represent all values of $z$ as points in the complex plane, what would be the set of points for which the series converges look like geometrically? The answer is simple - a circle!

Let’s start by talking about absolute convergence, which is the easiest kind to deal with. An infinite series $\sum w_n$ of complex numbers is said to converge absolutely if the series $\sum |w_n|$, or the sum of the norms of its terms, converges. It’s not necessarily obvious immediately why the convergence of the series $\sum |w_n|$ implies that $\sum w_n$ must also converge (i.e. that absolute convergence implies convergence), so let’s spell it out here briefly. If $w_n = a_n + b_n i$ where $a_n,b_n$ are sequences of real numbers, then

Because $\sqrt{a_n^2+b_n^2}$ is greater than both $|a_n|$ and $|b_n|$, it follows that $\sum |a_n|$ and $\sum |b_n|$ converge, and hence $\sum a_n$ and $\sum b_n$ converge, implying that $\sum w_n = \sum a_n + \sum b_n i$ converges.

Now let’s consider a complex power series of the form

(in this case, the coefficients $a_n$ are no longer intended to be strictly real numbers). Suppose we know that this series converges to a value $f(z_0)$ for some complex number $z=z_0$. Then, of course, we know that $|a_n z_0^n|$ approaches zero as $n\to\infty$ (but we do not necessarily know that the series is absolutely convergent). Knowing this, we may deduce that the series also converges at $z=rz_0$ for any complex number $r$ with $|r|<1$. How do we know? Well, if $|a_n z_0^n|$ approaches $0$ as $n\to\infty$, it follows that it is bounded above by some positive real number $B \ge |a_n z_0^n|$ for all $n$. This means that

which means that the real-valued infinite series $\sum |a_n (rz_0)^n|$ converges, by comparison with $\sum B|r|^n$ (which is just a simple geometric series that converges to $B(1-|r|)^{-1}$). This shows that $\sum a_n (rz_0)^n$ converges absolutely!

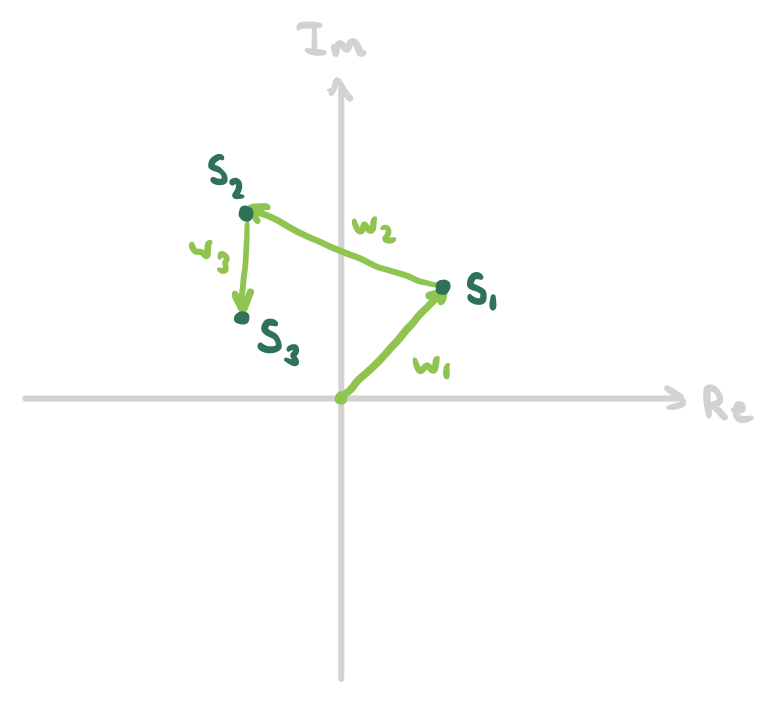

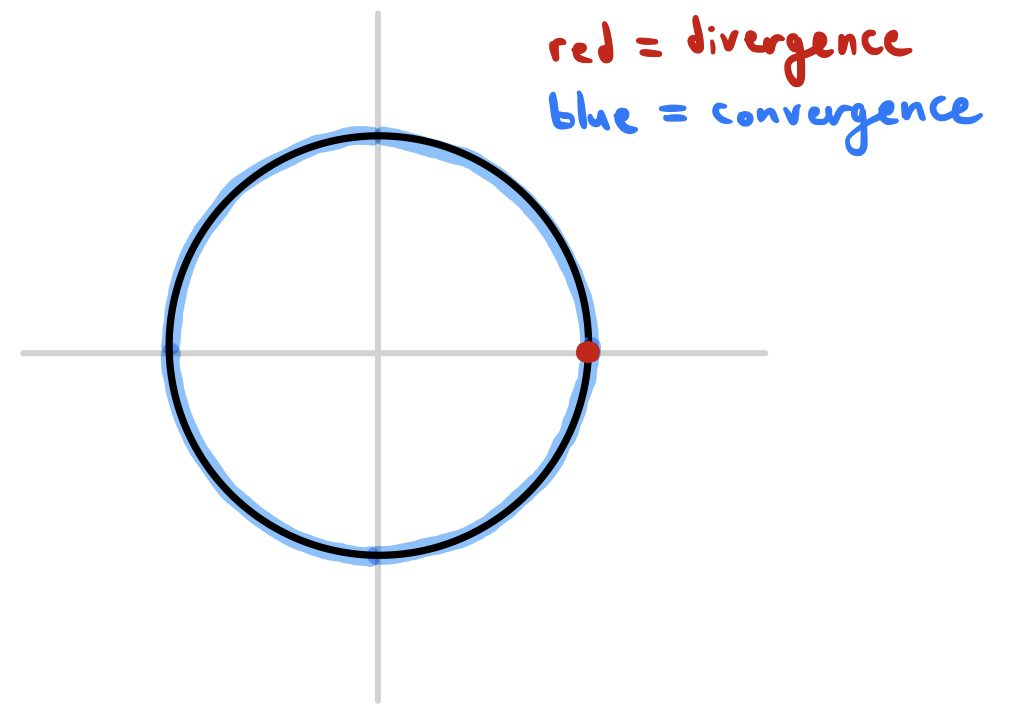

What does this mean geometrically? If $z_0$ is some point on the plane, then $rz_0$ can be any other point on the plane that is closer to the origin, since we specified that $|r|$ must be less than $1$. The set of complex numbers that are closer to the origin than $|z|$ is an open circle, which looks like this:

So, given convergence at a point $z_0$, all points on the interior of this disc are guaranteed to make the series converge as well, but we can’t conclude anything about points on the boundary or exterior of this disc. Since every point of convergence generates a whole open disc filled with points of convergence, we may conclude that one of the following cases must be true: either

This raises a couple more questions. When a complex power series has an open disc delimiting points of convergence from points of divergence (also called the circle of convergence) as described in case 3, how can we find out what the radius of this circle is? And we know what happens on the interior and exterior of the circle, but what about the boundary - what kind of convergence/divergence behavior occurs for points on the circumference of the circle of convergence?

We can answer the first question right away. Suppose that a circle with radius $R$ (equation $|z|=R$) is contained in the circle of convergence. Then the power series converges absolutely for all points on this circle, or in other words the real-valued series

converges (absolutely). This is true if and only if

by the well-known "root test" often used to test convergence of real-valued series. This is true if and only if

Hence, the "critical value" of $R$, or the maximum value of $R$ for which the open disc of radius $R$ is contained in the circle of convergences, is given by

which is the radius of the circle of convergence.

As for the convergence/divergence behavior on the boundary $|z|=R^*$ - that’s a trickier question than it seems at first, so we’ll return to it later.

In high-school precalculus, the "alternating series test" is commonly learned as a criterion for determining the convergence of infinite series with real terms. The theorem is as follows: if $a_n$ is a decreasing sequence of positive real numbers tending towards zero as $n\to\infty$, then the series

converges. Furthermore, the error $E$ in the Nth partial sum satisfies the following inequality:

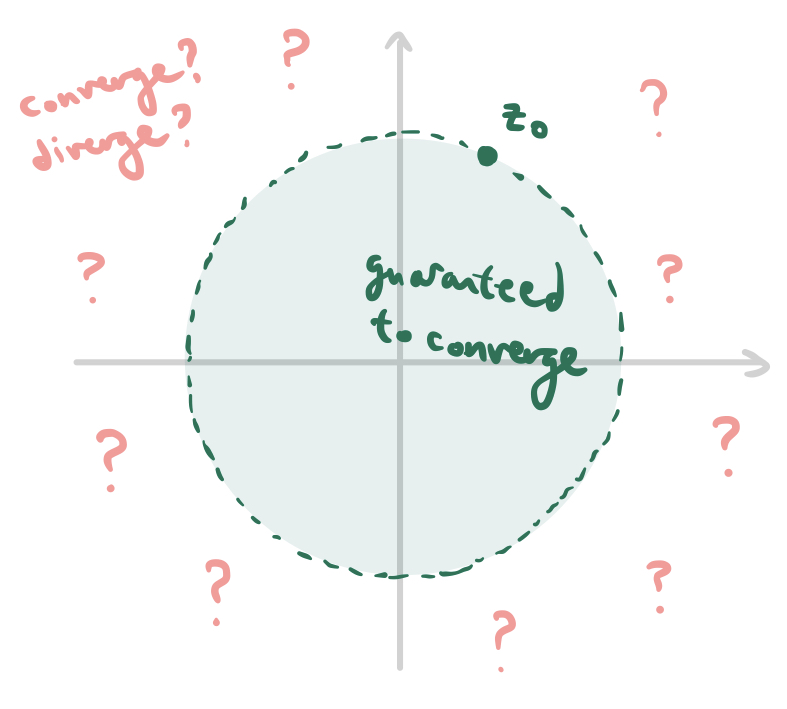

We can visualize this theorem by picturing the partial sums $S_N$ in relation to each other on a number line:

The alternating signs and decreasing magnitudes of terms imply that $S_{N+2}$ always falls somewhere in between $S_{N+1}$ and $S_N$. This, in turn, implies that the limiting value $S$ of the sum must lie somewhere in between $S_{N}$ and $S_{N+1}$ for each $N$, and, as a result, the error $|S - S_N|$ is less than $a_{N+1}$ because $S$ is "trapped" between $S_N$ and $S_{N+1}$.

Now let’s consider something a bit more complicated: the infinite series

where $\omega \ne 1$ is a complex number with $|\omega|=1$ and $a_n$ is a decreasing sequence of positive real numbers tending towards zero as $n\to\infty$. I claim that these conditions imply that the series converges, and in a moment we’ll derive an error bound similar to the one given for real alternating series. Note that this generalizes on real-valued alternating series: setting $\omega = -1$ gives us an alternating series of real terms just like the one we considered above.

The idea is to use a "trapping" argument like the one used for real-valued alternating series, but it gets a bit more complicated when our series has complex terms. Because the complex plane is 2-dimensional, unlike the 1-dimensional real line, it is impossible to "trap" a complex number between two other complex numbers. In other words, two real numbers partition the real line into three pieces, but two complex numbers do not divide the complex plane into pieces. This time we’ll have to get creative.

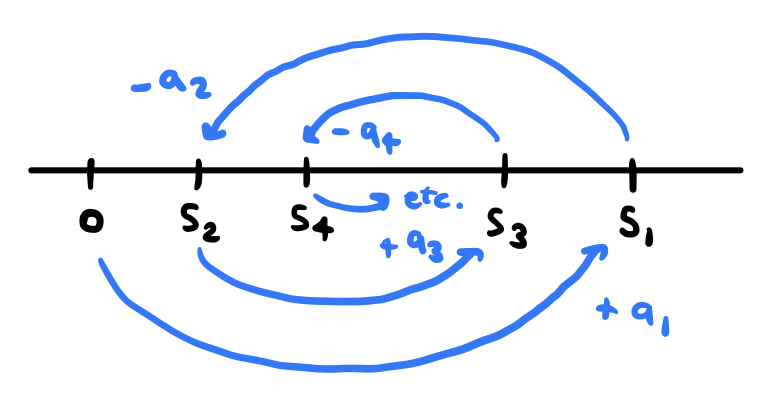

In our diagram for real-valued alternating series, the direction of the "jump" corresponding to each term $a_n$ alternated between positive (to the right) and negative (to the left). If we consider $\omega^n a_n$ to be a vector in the complex plane that points from $S_{N-1}$ to $S_{N}$, it does not reverse directions each time $n$ increments, but it always rotates by the same amount each time. To see this more clearly, write $\omega = e^{i\theta}$ for some real $\theta$ between $0$ and $2\pi$ (we may do this because $|\omega|=1$). Each additional factor of $\omega$ rotates the vector $\omega^n a_n$ by a counterclockwise angle $\theta$. So the sequence of terms and partial sums, when plotted in the complex plane, might look something like this:

Because the $a_n$ are decreasing and tending towards zero, these partial sums will gradually "spiral in" on some value. Of course, this is just an intuitive argument. Let’s show convergence more rigorously by "trapping" the partial sums as we did with real alternating series.

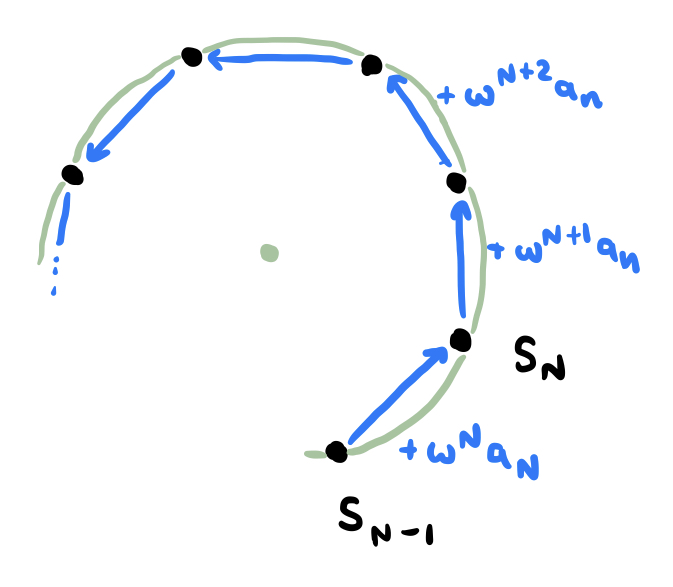

Suppose that we kept drawing this spiral up until a certain point $S_N$, and then after this point, instead of decreasing the magnitude of each subsequent term, we kept the magnitude constant, while continuing to apply the rotations resulting from multiplication by $\omega$. Instead of spiraling closer and closer to the point $S$, the subsequent partial sums would all lie on a circle, like this:

If we hold the magnitude of the terms constant at $a_N$, the subsequent partial sums lie on the boundary of this circle, but if we allow the terms to continue decreasing, the resulting spiral will necessarily lie entirely within the interior of this circle! In other words, all partial sums after $S_N$ lie on the interior of the circle which passes through the points $S_{N-1}$, $S_N$, and $S_N + \omega^{N+1}a_N$. This is still just intuition - let’s prove it using induction.

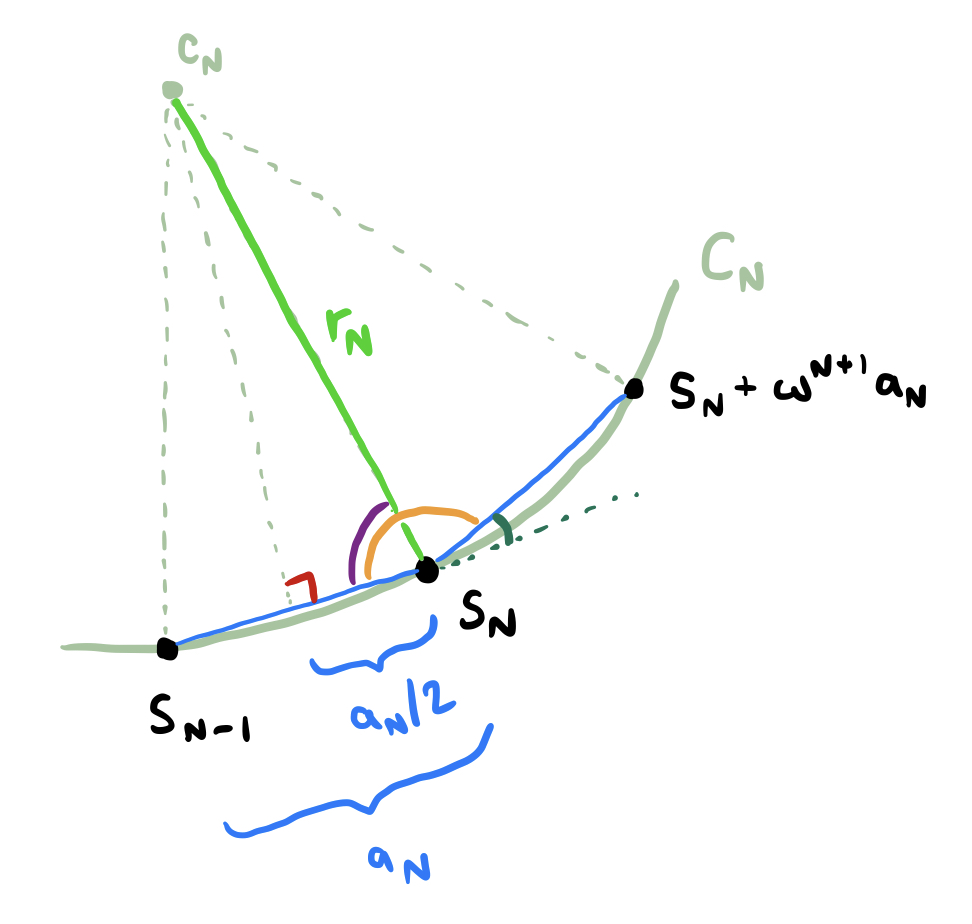

Consider the circle passing through the points $S_{N-1}$, $S_N$, and $S_N + \omega^{N+1}a_N$. Call this circle $C_N$. Let’s calculate its center $c_N$ and radius $r_N$. The following diagram should help:

The green angle is equal to $\theta$, meaning that the orange angle equals $\pi-\theta$ and the purple angle equals $\frac{\pi-\theta}{2}$. Performing some basic trigonometry on the pictured right triangle allows us to conclude that

or, equivalently,

This is our formula for the radius of the circle! Using a bit more trig, we may also calculate

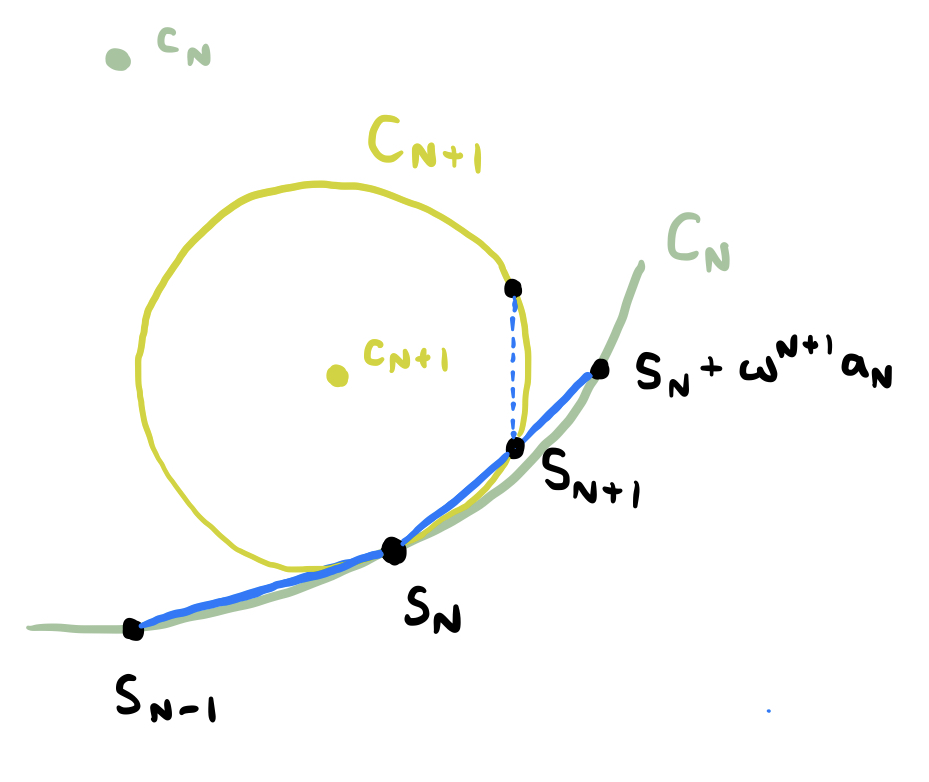

Now let’s consider the circle $C_{N+1}$ in relation to the circle $C_N$. This circle passes through the points $S_N$, $S_{N+1}$, and $S_{N+1}+\omega^{N+2}a_{N+1}$. Notice that the point $S_{N+1}$ must lie somewhere along the line segment joining $S_N$ to $S_N + \omega^{N+1} a_N$, since adding $\omega^{N+1}a_{N+1}$ moves in the same direction but "doesn’t get as far" because $a_{N+1} < a_N$. We have the following diagram:

The circle $C_{N+1}$ is tangent to $C_N$ at the point $S_N$, and using the formula we derived for the radii of these circles, we may say that $r_{N+1} < r_N$, because the ratio $r_{N+1}:r_N$ is equal to $a_{N+1}:a_N$, which is less than one. The tangency and smaller radius of $C_{N+1}$ allows us to include that it is entirely contained within the interior of the closed circle $C_N$. Inductively, because $S_{N+1}$ is always in the interior of $C_{N}$ and $C_{N+1}$ is wholly contained inside of $C_{N}$ (except at the point of tangency $S_N$), we may conclude that all partial sums after $S_N$ are contained within $C_N$. Notice also that

as a consequence of the fact that $a_N$ tends to zero as $N\to\infty$. This means that these "trapping circles" shrink smaller and smaller with their radii approaching zero, eventually closing in on a point, which corresponds to the value to which the infinite series converges. To put it more precisely: the set

is necessarily a singleton set with one element because the radii of the circles tend towards zero, and this element is $S$, the value to which the series converges.

So we’ve established convergence! But we can actually do a little better than this. Now that we know that the series converges to some value $S$, we can ask about the error $|S-S_N|$ in the Nth partial sum. Because $S_N$ lies on the boundary of the "trapping circle" $C_{N+1}$, we may say the distance between $S_N$ and any other point in/on $C_{N+1}$ is less than or equal to the diameter of the circle, or $2r_{N+1}$. Since $S$ is inside $C_{N+1}$, we have the following bound:

Cool! There’s one more interesting result that we can milk from everything we’ve done so far. The above argument relies on the fact that every point on the circumference of the circle is within a distance of the diameter length, or twice the radius length, from every other point in/on the circle. But if we consider the circle’s center instead, it’s guaranteed to be within half that distance, or the length of the circle’s radius. This means that, in general, $c_{N}$ may be a better approximation to $S$ than the partial sums $S_N$ themselves - because $|S-S_N|$ is guaranteed to be less than $2r_{N+1}$, but $|S-c_N|$ is guaranteed to be less than $2r_N$.

Well, that was a long section! If you found this method of handling "complex alternating series" interesting, here’s another question to ponder: using a similar technique, what can you say about the convergence of the sum

where $|\omega|=1$ and $a_n$ is a decreasing sequence of positive real terms tending towards zero, as usual? When it does converge, can you find an error bound? Can you generalize to sums of the form

where $b_n$ is an increasing sequence whose differences $b_{n+1}-b_n$ are positive and tend towards zero (as well as any other conditions you see fit to impose)?

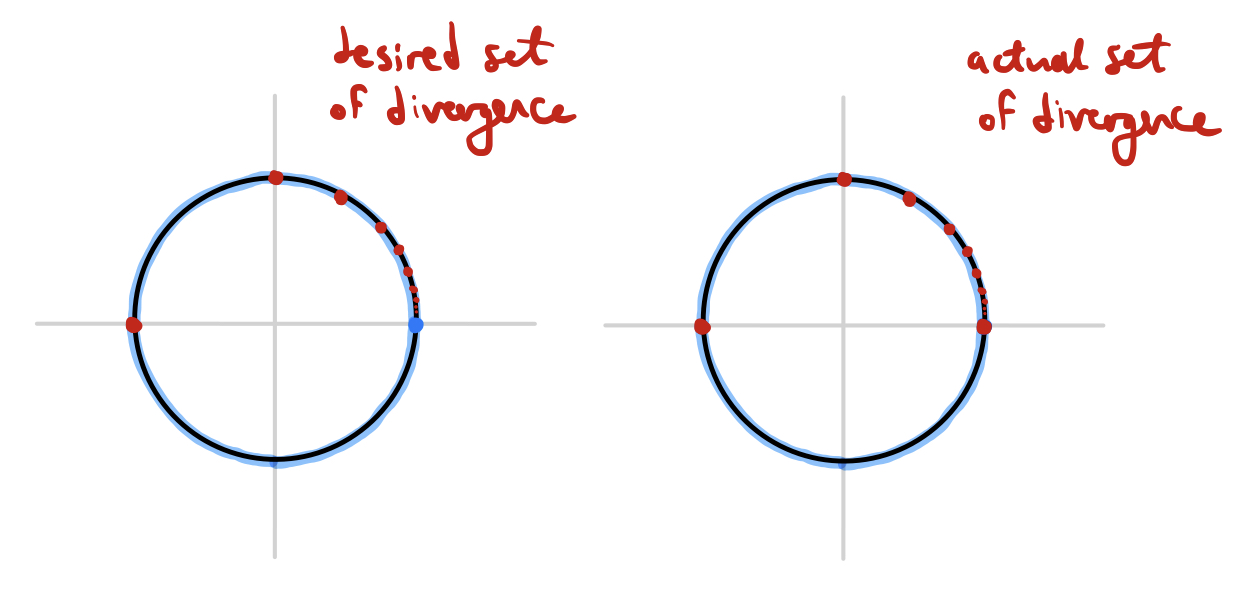

At this point we already know that all complex power series converge everywhere on the interior of their circle of convergence, and diverge everywhere on the exterior of their circle of convergence - but what about on the boundary? What sort of convergence/divergence behavior can be manifested on the circumference of the circle of convergence? Another question we might naturally ask is: given a subset $D$ of the unit circle, when is it possible to construct a power series $f(z)$ with radius of convergence $R=1$ that diverges on $D$ and converges everywhere else on the unit circle? In other words, which subsets of the unit circle can be "sets of divergence" of a complex power series?

For one, we know that it’s possible for a power series to diverge everywhere on the unit circle: take, for example, the series

This (geometric) series has radius of convergence $R=1$, but when $|z|=1$, the terms do not tend towards zero as $n\to\infty$, meaning that it converges nowhere on the unit circle. Thus, $D=\varnothing$ is a possibility - what more interesting sets could $D$ be?

Let’s proceed by considering this power series:

It’s easy to see that this series has a radius of convergence of $R=1$. (For the remainder of this section, we will mostly stick to discussing series with $R=1$ just for the sake of simplicity.) Inside of the circle $|z|=1$, it converges absolutely (the magnitudes of the terms decrease exponentially), but outside of the circle $|z|=1$, the terms increase exponentially and do not tend to zero as $n\to\infty$, so it diverges. But what about on the boundary? When $|z|=1$ and $z\ne 1$, we may apply the "alternating series test" we derived in the previous section to show that the series converges, since $a_n = 1/n$ is a decreasing sequence of positive real coefficients that tends to zero as $n\to\infty$. However, at $z=1$, we have

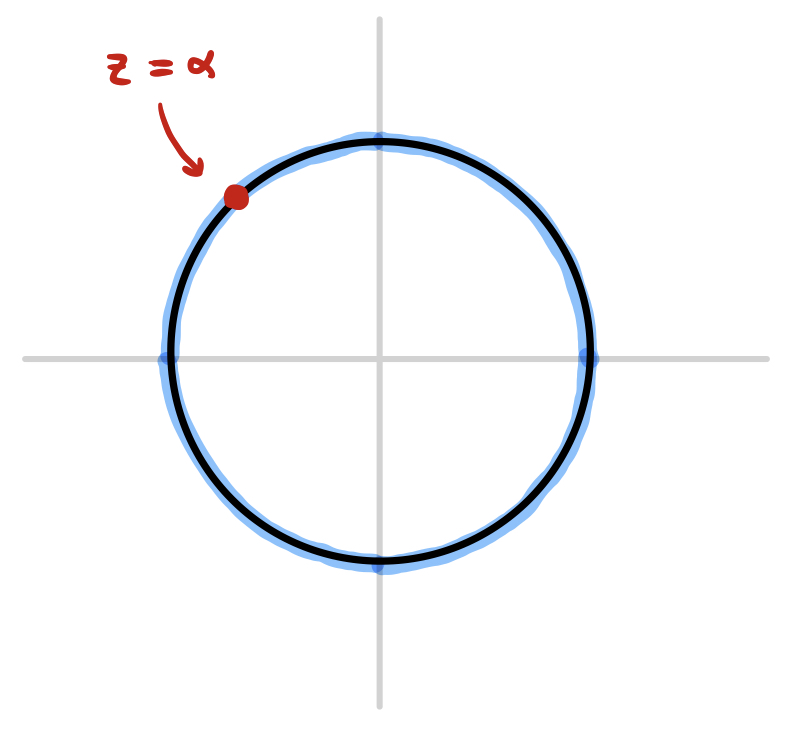

which is the harmonic series, meaning that it diverges! Thus, the "divergence set" of $\lambda$ on the unit circle just consists of the point $z=1$. We could sketch the convergence/divergence on the unit circle as follows:

Okay, cool - we’ve found a series that diverges at $z=1$ and converges everywhere else on the unit circle. Can we find a series that diverges only at $z=\alpha$ for some arbitrary $\alpha$ on the unit circle, diverging everywhere else?

It turns out that we can easily construct such a power series using $\lambda$ from the previous example. If $\lambda(z)$ diverges only at $z=1$, then $\lambda(z/\alpha)$ diverges only at $z=\alpha$, since $z/\alpha=1$ only when $z=\alpha$. In effect, dividing $z$ by $\alpha$ has rotated the whole complex plane about the origin in such a way that $1\mapsto \alpha$, "turning" the whole circle of convergence such that the single point of divergence moves to a desired position $\alpha$. Thus, the convergence/divergence of the series

can be pictured as follows:

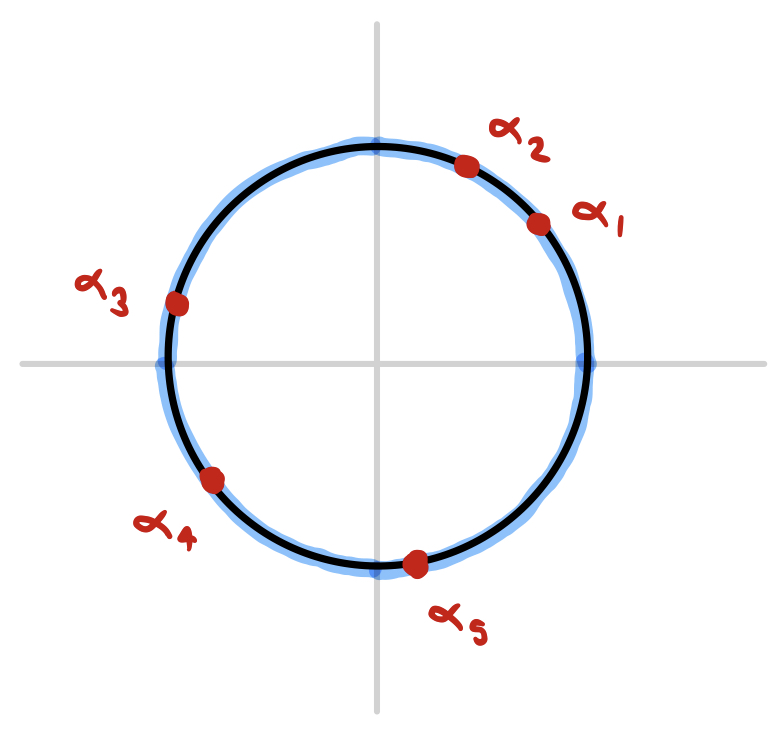

Okay, but why don’t we generalize even further? We’ve constructed a series that diverges only at a prescribed point $z=\alpha$ - can we construct one that diverges only at a prescribed set of points $\alpha_1, \alpha_2, ..., \alpha_k$?

This also turns out to be easier than expected! Since the series $\lambda(z/\alpha_i)$ diverges only when $z=\alpha_i$, then the series corresponding to the expression

will diverge only when $z$ equals any one of the $\alpha_i$. This is because when $z$ equals one of the $\alpha_i$, each of the $\lambda(x/\alpha_j)$ is convergent except the one with $j=i$, and the sum of finitely many convergent series with one divergent series is always divergent. If $z$ does not equal any of the $\alpha_i$, then each of the $n$ series is convergent, meaning that their sum is also convergent. If, for instance, we prescribed the divergence points $\alpha_1, ..., \alpha_5$, our circle of convergence might look like this:

Note that the sum of these terms can be rewritten in power series form as follows:

where the coefficients $A_n$ are given by

Now the next natural generalization to wonder about is: if we can prescribe finitely many points of divergence on the unit circle, can we prescribe infinitely many? This is where things start to get tricky...

But before we move on to that problem, consider the following question: can we also prescribe finitely many points of divergence for the series

if we are required to choose real coefficients $a_n$? In the construction above, the coefficient $A_n$ will usually take on a complex value, depending on the prescribed points $\alpha_i$ - but what if we are only allowed to use real coefficients?

It turns out that power series with real coefficients have a nice symmetry that restricts which sets $D$ can occur as their sets of divergence. Notice that

if the $a_n$ are real numbers. The conjugate of an infinite series converges if and only if the original infinite series converges, meaning that if the $a_n$ are real, the convergence of the series $f(z)$ is equivalent to that of $f(\bar{z})$. Recall that, geometrically, the transformationb $z\mapsto \bar{z}$ corresponds to a reflection about the real axis - which means that the divergence set of a complex power series with real coefficients must be symmetrical about the real axis!

Okay, so given some list of points $\alpha_1, ..., \alpha_n$ on the unit circle, we can only construct a power series with real coefficients diverging at precisely those points if they are symmetric about the real axis - that is, for each $\alpha_j$, there is some $\alpha_k$ with $\alpha_k = \bar{\alpha_j}$. Alternatively, we could attempt to construct a power series that converges only at the points $\alpha_1, \bar{\alpha_1}, \alpha_2, \bar{\alpha_2}, ..., \alpha_n, \bar{\alpha_n}$, where each $\alpha_j$ is on the upper-half circle (that is, $\alpha_j = e^{i\theta_j}$ where $\theta_j\in (0,\pi)$). We already know that we can construct a power series $f(z)$ that diverges precisely at the $\alpha_j$:

where

If $f(z)$ diverges at the $\alpha_j$, then $\overline{f(\bar{z})}$ diverges at the $\bar{\alpha_j}$, meaning that $f(z) + \overline{f(\bar{z})}$ diverges at each of the $\alpha_j$ and their conjugates. Now we may write

The coefficient of the $z^n$ term is equal to

which is guaranteed to be real, since the sum of any complex number with its conjugate is necessarily a real number! More generally, even if we’re dealing with more than finitely many points of divergence, if the divergence set $D$ of a power series $f(z)$ on the unit circle is contained within the upper-half circle, then the power series of $f(z) + \overline{f(\bar z)}$ diverges on the set $D \cup \bar{D}$, or the combination of $D$ and its reflection across the real axis.

Now that we’ve dealt with this little puzzle, we can move on to the tricky problem of prescribing infinitely many points of divergence for a complex power series...

To summarize: we noticed that if $|\alpha|=1$, the power series $\lambda(z/\alpha)$ always diverges at $z=\alpha$ and nowhere else on the unit circle. Then we noticed that summing finitely many series of the form $\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$ would result in a power series diverging at the points $\alpha_j$ and converging everywhere else on the unit circle.

When we try to construct a series diverging at infinitely many prescribed points, the first thought that comes to mind is just to try summing infinitely many series of the form $\lambda(z/\alpha)$. But then we run into a problem. If we take the sum

for some finite $k$, it is guaranteed to converge to some finite value as long as each of the terms is finite. However, if we let $k\to\infty$, this sum may (and probably will) diverge even if none of the $\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$ diverges, just because we are adding up infinitely many of them. How can we fix this?

The trick is noticing that, in the case of finite $k$, we need not necessarily just sum up the $\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$: rather, any weighted combination of the $\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$ will also have the desired convergence/divergence behavior. That is, we may consider the power series given by

where the $b_j$ are any complex nonzero constants we wish to choose. This is because multiplying a power series $\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$ by a nonzero constant $b_j$ does not affect its convergence/divergence, hence summing the weighted power series $b_j\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$ also produces a series that diverges precisely at the $\alpha_j$.

Now that we have some freedom in choosing the coefficients $b_j$, we may more effectively control the behavior of this sum of power series as we let $k\to\infty$. For example, if we let $b_j = 1/2^j$, we would have something of the form

We can’t say for sure that this diverges only at the $\alpha_j$ without knowing more about the sequence ${\alpha_n}_{n=0}^\infty$, but this sure looks promising - unless the values $\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$ grow exponentially in magnitude as a function of $j$, this series will converge because of the factor $1/2^j$.

One quick pedantic note before we get into the weeds and consider a few examples. The infinite series we have just considered is

which can also be written as a double infinite series

Written this way, this is not a power series. A power series must be written as an infinite sum of constant coefficients multiplied by $z^n$. The above is an infinite sum of power series, but we want a single power series whose coefficients are given by (convergent) infinite sums:

This can be accomplished by swapping the order of summation. However, swapping the order of summation is known not to always preserve the convergence of a double infinite series - there are some cases in which swapping the order of summation turns a convergent double series into a divergent one, or vice versa. So we need to be careful when doing this. I won’t go into the nitpicky details, but I’ve proven the following theorem on my own, to use as a criterion to justify swapping the order of summation in some of the examples I’ve done:

Let $\varphi:\mathbb N^2 \to \mathbb C$ such that the sum converges for any value of $n$, and the sum converges for any value of $m$. Furthermore, define the "error functions" $E_1,E_2$ as and If both of the following limits vanish: then it follows that and, in particular, each of these two double series converges if and only if the other converges.

Phew, that was a mouthful! I’m not gonna prove this theorem, and there’s probably a much more robust and elegant criterion out there for determining when it’s okay to swap the order of summation (something something uniform convergence?) but I am not aware of it, and this has sufficed so far for my purposes. I’m also not going to prove it here, even though the proof is pretty short - give it a shot yourself, if you want.

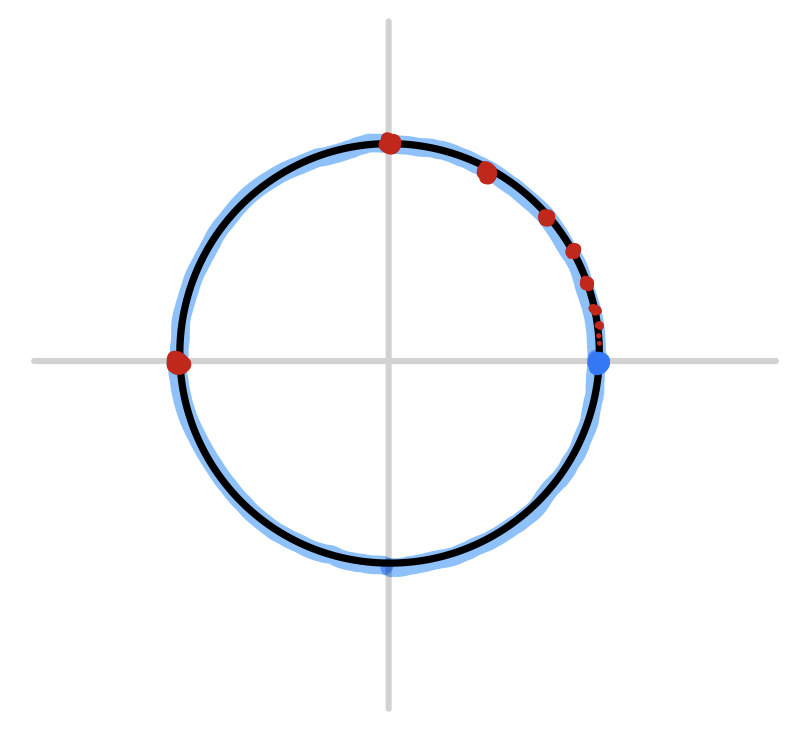

Now for a quick example. Let’s use $\alpha_n = e^{\pi i/n}$ as our sequence of divergence points, and try to construct a power series that diverges only at these points on the unit circle. Graphically, this set of divergence would look like

Now we need to choose a sequence of weights $b_j$ that will guarantee the convergence of the series

everywhere except at the prescribed points $\alpha_j$. In order to do this, we need to find an upper bound for the magnitude of $\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$. As it happens, the power series $\lambda$ can actually be calculated explicitly as an elementary analytic function wherever it converges: it is given by

which means that as $z$ approaches the divergence point of $\lambda$ at $z=1$, the value of $\lambda(z)$ diverges logarithmically. This implies that if $z=e^{i\epsilon}$ for some small $\epsilon$ (positive or negative), then the magnitude of $\lambda(z)$ behaves like $\ln|\epsilon|$. Thus, since $\alpha_n = e^{\pi i/n}$, we may say that the magnitude of $\lambda(z/\alpha_n)$ behaves asymptotically like $\ln|1/n|$, or $\ln|n|$. Thus, if we choose a sequence of weights like $b_j = 1/2^j$, the magnitude of the jth term of the series will be something like

as $j\to\infty$, the sum of which converges! Hence, this choice of weights guarantees convergence everywhere except at the $\alpha_j$ - and the fact that $\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$ diverges at $z=\alpha_j$ ensures divergence at each of the prescribed points, so we’re done.

However, not just any choice of $b_j$ would work. Suppose we chose $b_j = 1/j\ln^2(j)$. Even though the infinite sum of the weights $\sum b_j$ converges (which can be proven via the integral test), the magnitudes of the terms of our infinite sum of power series would behave like

But the sum of the above from $j=1$ to $\infty$ diverges! (You can also prove this using the integral test.) Hence, if we chose this sequence of weights, our construction would also diverge at the point $z=1$, which we did not prescribe!

The reason this problem occurs is because $z=1$ is a limit point of the prescribed divergence points $\alpha_j$ - that is, the prescribed divergence points "get arbitrarily close" to $z=1$, and since $\lambda(z/\alpha_j)$ gets "big" whenever $z$ gets "close enough" to $\alpha_j$, their infinite sum will diverge unless their growth is properly counterbalanced by the rate of decrease of the weights $b_j$.

In general, when we construct a power series with prescribed points of divergence this way, the only points at which we need to worry about unprescribed divergence are the limit points of the sequence ${\alpha_n}_{n=1}^\infty$. I’ve come up with the following theorem:

If the sum of weights $\sum b_j$ converges absolutely, then the infinite series and its corresponding power series diverge at the points $\alpha_j$ and converge at every point on the unit circle which is not a limit point of the sequence ${\alpha_n}_{n=1}^\infty$. However, convergence/divergence at the limit points of the sequence cannot be determined from the above information.

Again, I won’t go into full detail here, but the gist of the proof is as follows: if $z=z_0$ is not a limit point of the sequence of $\alpha_j$, then there exists a minimum distance $\delta > 0$ such that $z_0$ is at least a distance $\delta$ away from each $\alpha_j$. This means that the magnitude of $\lambda(z_0/\alpha_j)$ is bounded by some constant $B$, and the magnitude of the jth term of the infinite sum is consequently bounded by $|B|\cdot |b_j|$, meaning that it converges absolutely by comparison with $|B|\sum |b_j|$ (whose convergence follows from the absolute convergence of \sum b_j, which was assumed). Easy peasy!

So, perhaps this result isn’t quite as strong as we would like, and there are still a few questions left open. Is it always possible to choose the weights $b_j$ in such a way that ensures convergence at all of the limit points? (That is, can we always find a sequence of weights that "decreases fast enough"?) Can we always choose weights that ensure divergence at all of the limit points? Unfortunately, we’ve reached the limits of what I’ve been able to figure out on my own so far - maybe I’ll make some progress on these questions eventually and return to them in a future blog post. I suspect I’ll have to brush up on my topology and set theory a bit in order to answer these questions.

As usual, there are several interesting tidbits that I didn’t quite have room to explore thoroughly in this post, so I’ll cram them all into this final section under the pretense of "exercises for the reader". Some are stolen from various places around the internet, and some are of my own invention. First, here are a couple puzzles that involve some pathological examples of power series with interesting sets of divergence on the unit circle:

Consider the power series Prove that its set of convergence is dense on the unit circle, and it set of divergence is also dense on the unit circle. Can you find sone values of $z$ at which it converges and diverges (other than the obvious divergence at $z=1$)? Can you characterize all points on the unit circle at which it diverges? It might help to do a bit of reading about Beatty sequences.

Consider the power series Again, prove that both its set of convergence and its set of divergence are dense on the unit circle, and find some values of $z$ at which it converges and diverges.

Consider the power series Prove that this power series diverges whenever $z$ is a root of unity. Can you find other values of $z$ for which it diverges? Can you find explicit values of $z$ for which it converges? Does it converge or diverge at $z=e^{ie/2\pi}$?

And in closing, here are some more general questions. Some of them I’ve solved, others I haven’t - but I’m not gonna say which!