Lately I've been trying to solve some more complex programming problems in Brainfuck, as a way of giving myself a better sense of how to carry out low-level memory management. When I say "complex", I don't really mean actually complex programming problems - only complex compared to what is usually feasible in Brainfuck. Whether you've never heard of Brainfuck before, or have actually spent some time playing with it, I encourage you to follow along! A little while ago I wrote a simple interpreter that allows you to watch your code being executed, which makes things a hell of a lot easier than trying to picture everything in your head.

Since there are probably some subtle differences between different implementations of Brainfuck, I thought I'd list out some details here that I'm assuming, which may or may not be standard. If anyone does decide to follow along with my examples, I don't want to confuse them by having a variation of Brainfuck that's slightly different than the "usual" implementation in ways that aren't made explicit. So for the sake of clarity, I'm assuming:

Clearly this has some significant differences from actual low-level computer architecture, but I think there's something to be learned about low-level memory management from Brainfuck. In the final section, though, I'll show off a phenomenon that illustrates a stark difference between this memory model, which treats natural numbers as primitive, and the usual memory model, which treats bits as primitive.

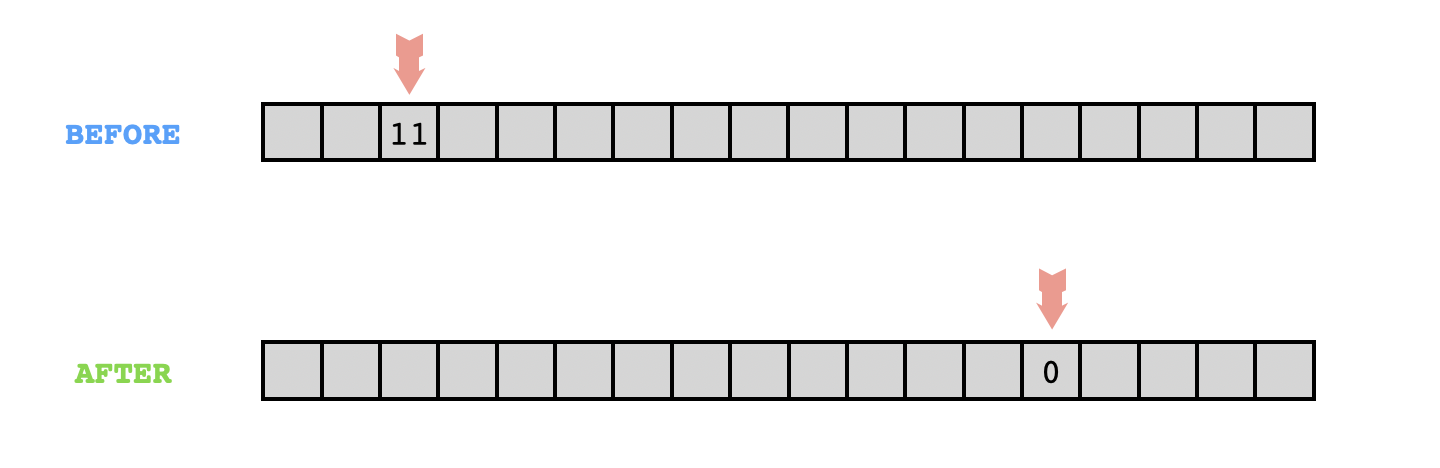

Here's a simple problem to solve in Brainfuck. How can we write a program that takes a natural number as input, and moves the pointer that many cells to the right? That is, the head should start on a cell containing the number $n\in\mathbb N$, and end up $n$ cells to the right. Let's also assume that there isn't any "garbage" in these other cells to begin with (they should all contain zeros initially), and additionally let's try to design our program in such a way that it doesn't "create garbage", or leave any nonzero cells in its wake when it finishes.

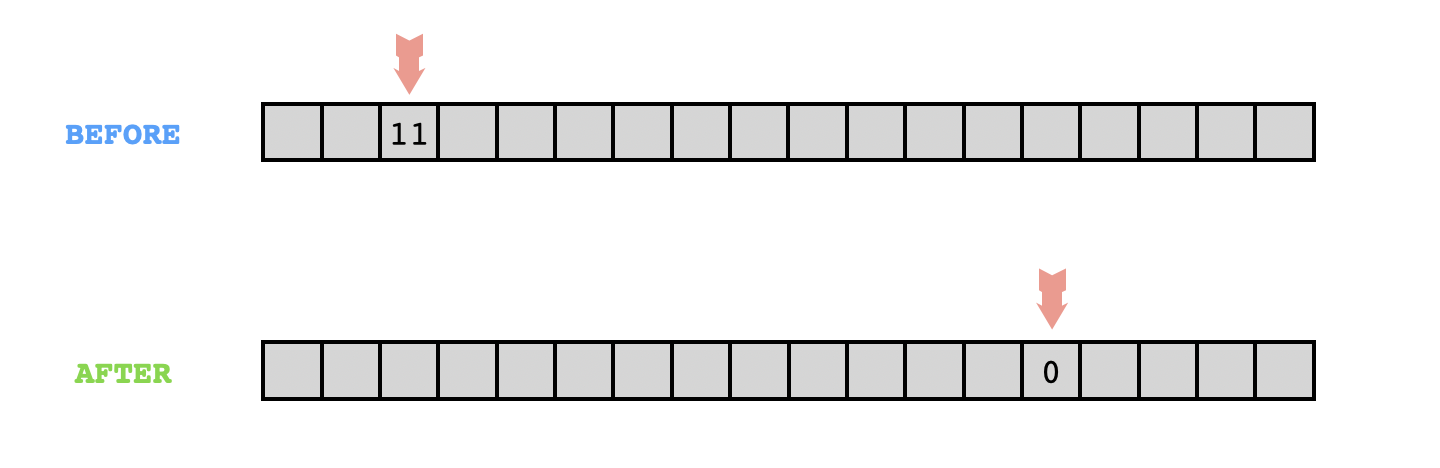

Notice that there's a certain symmetry to this problem that we can exploit: moving the pointer $n$ cells to the right is the same as moving it $1$ unit to the right, and then moving it $n-1$ more units to the right. This means that if we can write a subprogram that has the following behavior, then we can iterate it to obtain the desired right-shifting program:

It's not too hard to write a program with the above behavior, though. The following will do: which works for nonzero values of $n$. After executing this snippet once, we will have moved one cell to the right and decremented the contents of the cell telling us how many more cells we need to move to the right. This means that simply repeating the above until this number is zero will get the job done: Notice that to move $n$ cells to the right, this code requires $\Theta(n^2)$ time. This might seem horribly inefficient, but remember, we're doing in Brainfuck here.

We can actually solve this problem in $o(n^2)$ time, though it's not immediately obvious how. Here's a program that I've written which accomplishes the same task in $\mathcal O(n\sqrt n)$ steps, but I'll leave it for you to decipher if you're curious:

,[->+>>>+<<<<]

>>+>>

[

>>>+

[-<+<+>>]

<[->+<]<

[[<[-<]<[>]]>>-]

<

] >>>-

[-

<<<<<<<+>>>>>>>

<+[-<+<+>>]<<[->>+<<]>

[-<<<<->>>>]

>>

]

<[-]<<<<-<<

[

>[

-

[->+<]

<[->+<]>>

]<

[->+>+<<]>>[-<<+>>]<<-

] >-By the way, the above problem is a really good demonstration of how logistically different it can be to handle dynamic quantities as opposed to static quantities. In this problem, the number of cells to move to the right is input by the user, meaning that it's not determined until runtime. Indeed, this is the principal source of difficulty in designing the above algorithm, and it's also why it is seemingly so inefficient - it needs to work for any conceivable input. Note that if we needed to write a program to move $n$ cells to the right for some fixed $n$ chosen beforehand, not specified by the user, then the following simple program would work: and furthermore it would accomplish this task in only $\Theta(n)$ moves, and without actually needing to increment or decrement the value in any cell.

In any case, abhorrent runtime aside, our dynamic movement algorithm suffers from another problem. It relies on all of the cells between the starting cell and the ending cell being empty. This means that our attempts to move a dynamically-specified number of cells to the right will be "blocked" by any data that already exists there. What if, say, we wanted to store a list of integers in consecutive cells, and dynamically access the nth element of the list?

The solution is to not store the values consecutively. If we leave "gaps" between the values, we can make use of these unused cells as "scratch space" to perform the calculations necessary to move our pointer to the correct position. In the next section we'll see a demonstration of this.

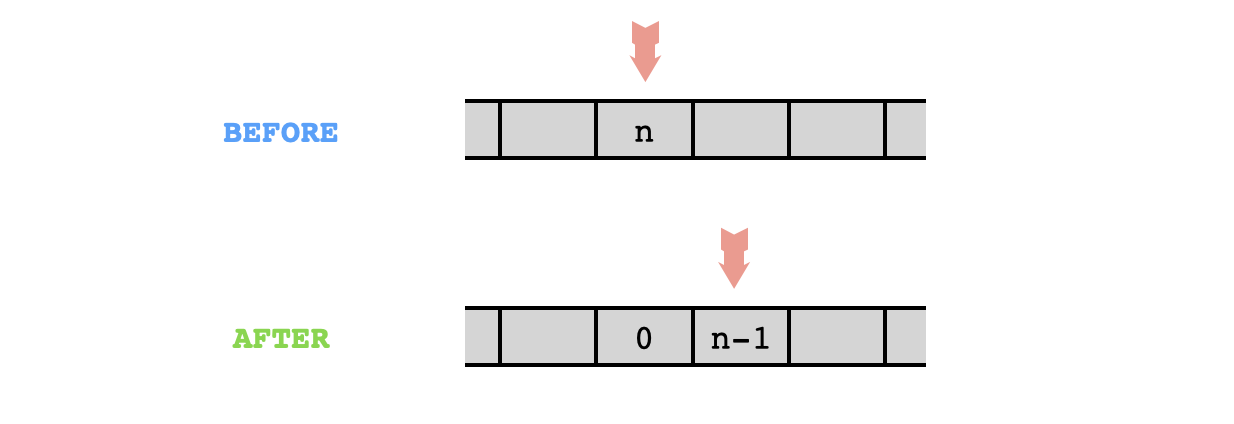

To illustrate what we've discussed above, I'd like to explore the problem of writing a program that outputs a list of powers of two, where the (nonzero) powers are input by the user. For instance, if the input is $\texttt{4,3,4,2,1}$ then the output should be $\texttt{16,8,16,4,2}$. This is a pretty simple problem and it can be solved without any fancy memory trickery. First of all, if the head is pointing at a cell and the cell immediately to the right is zero, we can easily double the value in the current cell using the following program: and if the number in the starting cell is $n$, this takes $\Theta(n)$ time. So if we want to calculate a certain power of two, we just need to repeatedly double the entry in a cell which starts out with the value $1$, where the number of doubling iterations is controlled by a third cell. The following program accomplishes this, taking the exponent as input from the user and outputting the desired power of two: For instance, with an input of $5$, some of the intermediate steps will look like this:

If we want to take several inputs from the user, we can accomplish this with just a slight modification of the code: which solves the original problem. But this solution has a terrible inefficiency - it computes every power of two that the user inputs completely from scratch. After all, if the user asks us to compute $2^5$, and then asks us to compute $2^4$, it seems kind of silly to compute $2^4$ all over from scratch when we've already calculated it as an intermediate step while computing $2^5$. It takes $\Theta(2^n)$ time to compute the nth power of two using the above algorithm, meaning that if we are given $n$ inputs, with the maximum among them being $M$, then the best we can guarantee with the above algorithm is that the runtime will be $\mathcal O(n\cdot 2^M)$. (The worst case occurs when the user asks for the same power of two $n$ times, in which case the inefficiency is particularly striking - we would be recomputing the exact same number several times!)

The solution is memoization. Each time we compute a power of two, we should save the result somewhere, so that if we are asked to compute it again later, we can simply reference the result that has already been calculated. But as we observed in the previous section, we can't store a list of data contiguously and still be able to visit arbitrary indices of that list dynamically. So how can we implement memoization?

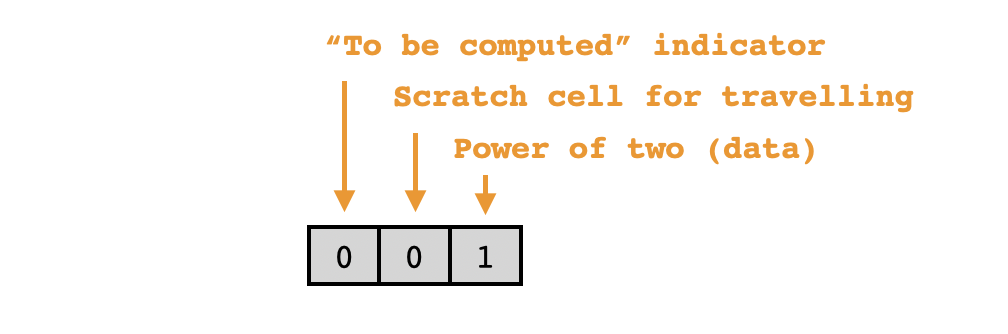

Rather than storing precomputed powers of two contiguously, we'll store what I'll refer to as "list records". These will consist of chunks of $3$ contiguous cells in which the third cell stores the data (a power of two, which at any given time may or may not have been computed yet) and the other two cells are used to help with bookkeeping. The first cell will serve as a "to be computed" indicator, with a value of $0$ indicating that the data cell of the list record has already been filled with its corresponding power of two, and a value of $1$ indicating that the next power of two remains "to be computed". The second cell will be used to help us traverse the list during execution and find the correct entry corresponding to the power of two we seek at any given time.

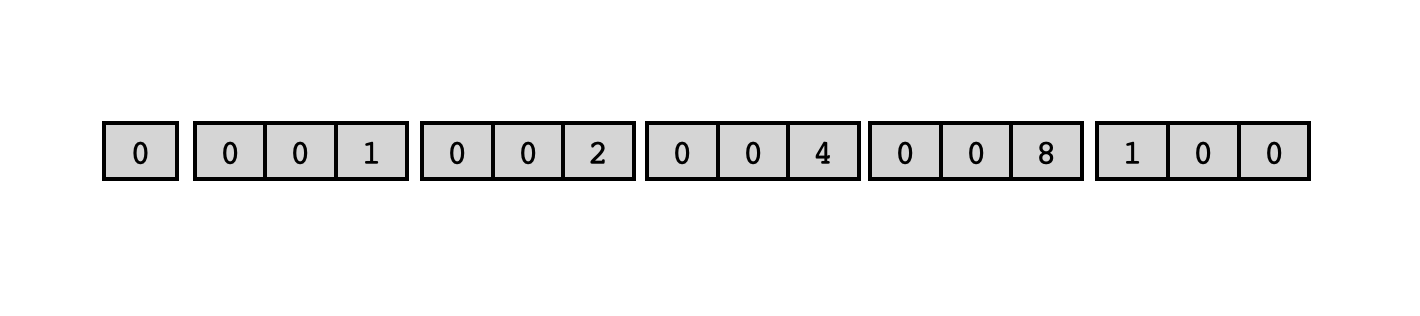

At any given time during the program's execution, only finitely many of the powers of two will already have been computed and stored in their corresponding list records. These powers of two will be present in the respective data cells of a sequence of contiguous list records, and at the end of this sequence of filled list records, there will be a single empty list record whose "to be computed" flag is turned on. For instance, if the largest power of two computed so far has been $16$, the program's memory might look like this:

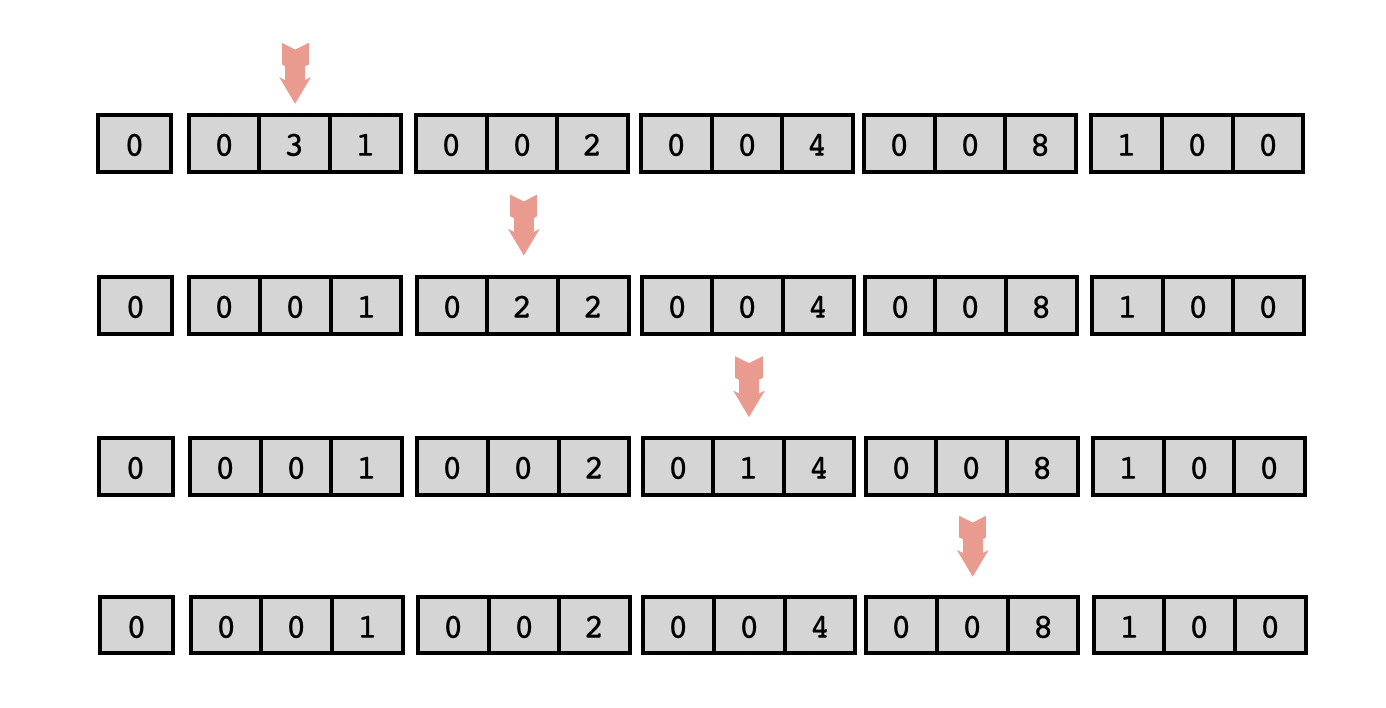

The second cell in the list records will serve as "scratch space" where we'll keep track of how far to the right the record we're looking for is located. For instance, if we've already computed the powers of two up to $16$ as shown above, and the user asks us to compute $2^3$, some of the intermediate steps will be as follows:

Each time we move the head to the next list record in search of a particular power of two, however, we must check whether or not a power of two has already been stored there. If it has not, then it needs to be computed at that very moment. This is where the "to be computed" indicator comes in handy. If this cell of the next data record is zero, we need to compute and fill that cell with the next power of two, and then activate the "to be computed" cell of the next data record.

Without further adieu, here is my annotated powers-of-two algorithm that takes advantage of memoization:

>>>+>+<<

,[

[

[->>>+<<<]>>>-

<[-<[->+>>++<<<]>[-<+>]>>>+<<<]>

]

>.

[<<<]

>>

,]I'd paraphrase this algorithm as follows:

The runtime of our new algorithm is $\mathcal O(nM^2 + 2^M)$. When the input contains a large power, this will be a very significant improvement. If you want to get a sense of just how much faster this can be, try out both algorithms on the sample input $\texttt{7,7,7,7,7}$.

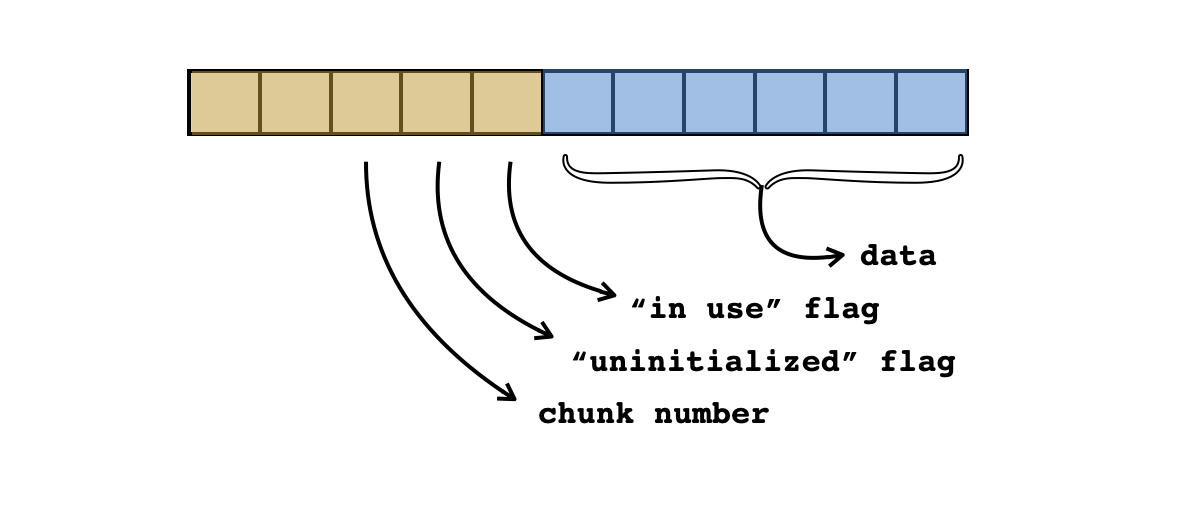

We can generalize the technique we used to solve the previous problem and use it to design a kind of makeshift "memory architecture" for Brainfuck that will make it easier for us to solve almost any problem. We've seen that it's useful to divide the memory into pieces which alternate between "scratch cells" used for navigation and for storing "metadata" about each piece (e.g. about initialization) and "data cells". Let's refer to these pieces of memory as chunks. In rough analogy with actual computer architecture, we might refer to the cells in a chunk that store data as minimal addressable units (MAUs) and the other cells used for traveling between addressable units as bus cells. Both the size of the bus and the size of an MAU should be static properties of our programs. For instance, in our powers-of-two program, we had $\mathtt{MAU} = 1$ and $\mathtt{BUS} = 2$, and $\mathtt{CHUNK}=3$.

In our memory architecture, the last three bus cells of a memory chunk will be used to store metadata about the chunk, the previous cells of the bus will be used for computations and movement between chunks, and the data cells will, of course, be used to store data.

If we decide on a chunk size of, say, $5$ for some program that we write, we can probably expect the sequences of commands $\texttt{>>>>>}$ and $\texttt{<<<<<}$ to show up all over our code. And if we accidentally type $4$ or $6$ arrows in some place where we intend to type $5$, we're going to cause errors that are extremely annoying to hunt down. So let's instead write a macro for our Brainfuck program that allows us to indicate that we want to repeat a command a fixed number of times without writing all of them by hand. Then we can use a simple text-substitution script to iterate through our code and replace the occurrences of this macro with the correct Brainfuck code.

The macro we write will act as follows: The following shell script performs this text substitution:

perl -pe 's/SREPEAT\(([^\(;]+);(\d+)\)/"$1"x$2/ge'So that, for instance, if the input code consists of the text $\texttt{SREPEAT(>;5)}$, the output code will read $\texttt{>>>>>}$. Note that the above script only performs the text substitution once, meaning that, for instance, the code would not be replaced with correct Brainfuck code, but rather To support nested $\texttt{SREPEAT}$ macros, we will have to modify our shell script to repeatedly expand the macro until no further occurrences of it are found in the input file.

We can also create macros for the parameters $\mathtt{MAU},\mathtt{BUS},\mathtt{CSIZE}$ of our memory architecture, and for some common sequences of moves that we will use often in our programs. I won't explain the Brainfuck code for each of the macros listed below, but I've included descriptions of their behavior:

| Name | Purpose |

| $\mathtt{RMOVE(X)}$ | Move the number from the current cell into an empty cell $\mathtt{X}$ units to the right. |

| $\mathtt{LMOVE(X)}$ | Move the number from the current cell into an empty cell $\mathtt{X}$ units to the left. |

| $\mathtt{RDUP(X;Y)}$ | Duplicate the number from the current cell into an empty cell $\mathtt{Y}$ units to the right, using a cell $\mathtt{X}$ units to the right as scratch. |

| $\mathtt{LDUP(X;Y)}$ | Duplicate the number from the current cell into an empty cell $\mathtt{Y}$ units to the left, using a cell $\mathtt{X}$ units to the left as scratch. |

| $\mathtt{TODATA}$ | Move from the beginning of the bus to the beginning of the data section in a chunk. |

| $\mathtt{TOBUS}$ | Move from the beginning of the data section to the beginning of the bus in a chunk. |

| $\mathtt{NEXTCHUNK}$ | Move from the beginning of a chunk to the beginning of the next chunk, initializing it if it has never been visited before. Requires at least $6$ units of bus space. |

| $\mathtt{PREVCHUNK}$ | Move to the previous chunk. |

| $\mathtt{PTRGO}$ | Move from the beginning of the zeroth chunk to the nth chunk, where $n$ is the value of current cell. |

| $\mathtt{INITMEM}$ | Initialize the first chunk. Should be called at the beginning of any script, and in particular, before ever calling $\mathtt{NEXTCHUNK}$. |

When we expand the above macros, though, we might inadvertently introduce redundant code. For instance, with a MAU size of $4$ and a bus size of $4$, the code $\mathtt{PREVCHUNK TODATA}$ would be expanded to but the substring of code $\texttt{<<<<>>>>}$ is completely superfluous, since it just moves the head four units to the left, and then four units back to the right again. To make sure the convenience of using macros doesn't come at the expense of producing code with obvious inefficiencies like the above, I've added a few additional text substitution steps to my script to iteratively remove all occurrences of the following superfluities:

If you want to check out my finished script and use it to write some Brainfuck code of your own, you can find it in this public Gist. I've also configured it to print information about the size of the code following macro expansion and superfluity elimination. For instance, if the following code is stored in sample.bf:

SREPEAT(SREPEAT(>;5)<<+++;10)---

The output of my script is as follows:

% ./memorymacros sample.bf 0 0

Beginning macro expansion. Initial code size:

34 sample.bf

Macros expanded. Intermediate code size:

105 sample.bf.tmp1

Code cleanup finished. Final code size:

57 sample.bfout

and the final expanded and compressed code is stored in sample.bfout:

>>>+++>>>+++>>>+++>>>+++>>>+++>>>+++>>>+++>>>+++>>>+++>>>

Counting sort is a linear-time sorting algorithm that's intended for sorting unordered lists of positive integers that are bounded in side. When I first started playing around with Brainfuck, I couldn't have imagined implementing a sorting algorithm (granted, counting sort is one of the simpler ones), but using the very same memory management trick that we used to compute memoized powers of two, we can implement counting sort without too much difficulty. But because the bookkeeping necessary to implement counting sort is more involved, we'll use the macro expansion tools developed in the previous section to make our lives easier.

Here's my unprocessed implementation of counting sort:

INITMEM

,[

PTRGO

TODATA + <<<

[PREVCHUNK] >>> TOBUS

,]

NEXTCHUNK

TODATA <<<

[>>>[-<<<.>>>]<<< >>>TOBUS SREPEAT(>;CHUNK) TODATA<<<]

>>>TOBUS [PREVCHUNK]

This is nice and readable. We can essentially read off the counting sort algorithm from this code:

And here's the processed version of this code, using a six-cell bus and single data cell for each memory chunk::

>>>>>>>>>>>+<+<<<<<<<<<<,[[>>>>>>>>>>>[->>>>>>>+<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<[-<<+>+>]<<[->>+<<]>[->>>>>>>+<<<<<<<]>>>>>>>[->+<]+>>]<<<<<<<<<<<-[->>>>>>>+<<<<<<<]>>>>>>>>>>>[->>>>>>>+<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<[-<<+>+>]<<[->>+<<]>[->>>>>>>+<<<<<<<]>>>>>>>[->+<]+>>]<<<<]>>>>>>+<<<[<<<<<<<]<<<,]>>>>>>>>>>>[->>>>>>>+<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<[-<<+>+>]<<[->>+<<]>[->>>>>>>+<<<<<<<]>>>>>>>[->+<]+>>]<[>>>[-<<<.>>>]>>>>]<<<[<<<<<<<]

How disgusting - but it works! The traditional counting sort algorithm is usually described as having a computational complexity of $\Theta(Bn)$, where $B$ is an upper bound on the positive integers to be sorted and $n$ is the number of elements in the input list. For our implementation in Brainfuck, though, a more realistic bound would be $\mathcal O(B^2 n)$, since it can take us $\Omega(a^2)$ steps to move the head out to the memory address $a$. If we wanted to take the time to implement our asymptotically more efficient head positioning algorithm as a memory management macro (which would require more bus space), we could get this down to $\mathcal O(B^{3/2}n)$.

I'd like to try implementing more complex sorting algorithms, like insertion sort, bubble sort and merge sort as well. But I'm still working on this!

We have taken some liberties with our mathematical model of Brainfuck, one of which is the assumption that a cell may contain any natural number, value rather than, say, a natural number value of a bounded size. The standard implementation of Brainfuck, as far as I'm aware, treats the cells like bytes, so that each one has a maximum value of $2^8-1$, after which incrementing causes overflow back to zero. While this assumption isn't really essential for many of the algorithms outlined above, allowing them to easily be ported to a bounded implementation of Brainfuck. But what follows is a phenomenon that is unique to this variant of Brainfuck, and wholly unrepresentative of low-level memory management on real computers.

The phenomenon I'm referring to is the ability to perform lossless compression that works on all inputs. In real-world computing, where units of memory store binary bits, it takes no more than a simple application of the pigeonhole principle to show that it's not possible to perform lossless compression of a certain number of bits into a fewer number of bits. This is because there are $2^b$ possible bit sequences on $b$ bits, meaning that if $m>n$, there cannot be an injective function from the set of bit sequences with $m$ bits into the set of bit sequences with $n$ bits, because $2^m > 2^n$. (This is a simple application of the pigeonhole principle.)

But in our idealized model of Brainfuck, a single cell consists not of a single bit, nor even of some value taken from a finite set of possible values, but rather of an arbitrary natural number. This means that a single cell can, in this formalization, contain any one of an infinite number of values. It's a fact that there does exist an injection from $\mathbb N\times\mathbb N$, the set of possible states of a pair of cells, into $\mathbb N$, the set of possible states of one cell. In fact, the following is a bijection $\mathbb N\times\mathbb N\to\mathbb N$: We can actually implement this mapping, and its inverse, in Brainfuck. This will allow us to losslessly compress two cells into a single cell and decompress the value in that single cell back into the original pair of values that produced it - something that's impossible to accomplish with bits.

Computing the triangular numbers is pretty straightforward in Brainfuck. The following code can be used to compress pairs of values $(m,n)$ into a single value:

[->+>>+<<<]>

[

[->+<<+>]

>-[-<+>]<

]

>>[-<<<+>>>]<<<

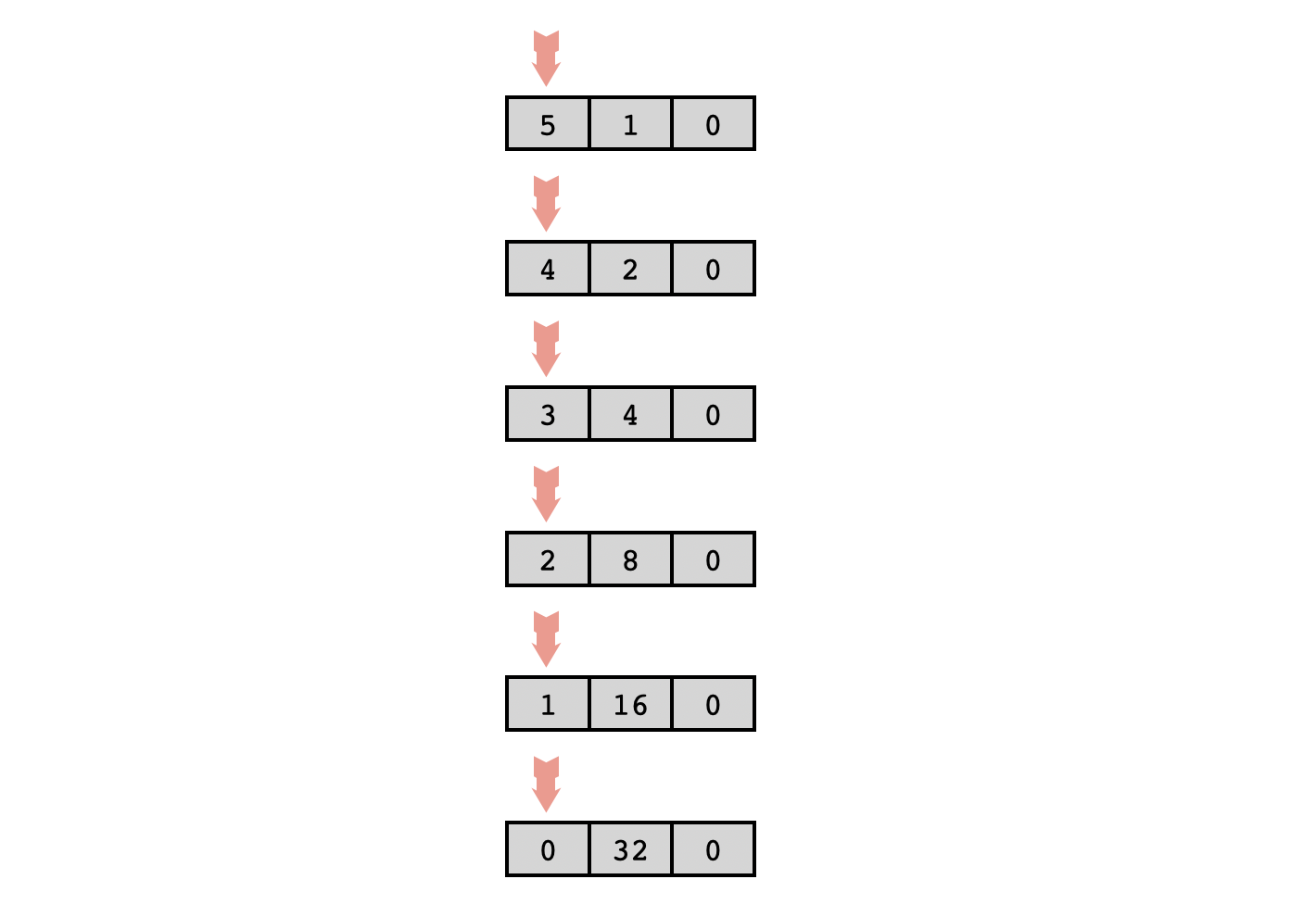

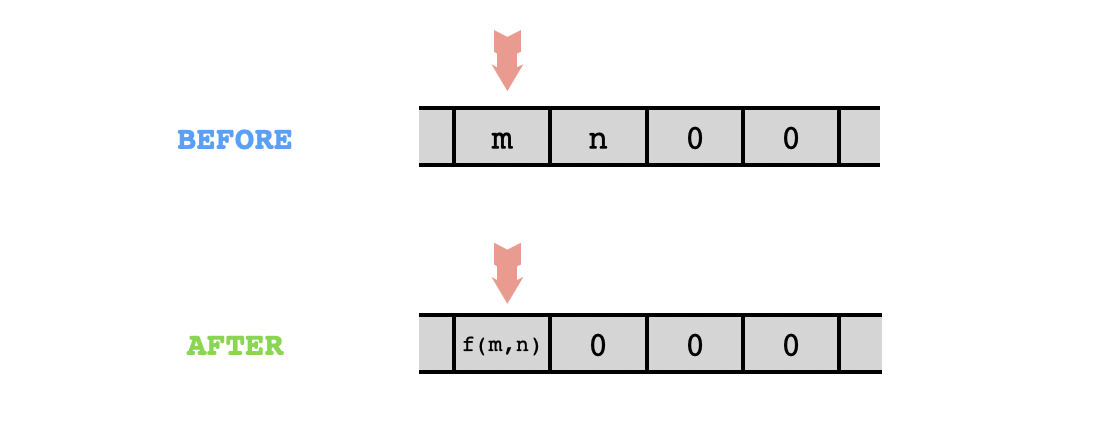

It requires $4$ cells of memory, including the two cells of memory to be compressed and two additional empty cells to be used as "scratch space". It acts on these cells as follows:

The inverse mapping is a little more complex to implement. To extract from the number the pair of numbers $(m,n)$, we can first compute the index of the largest triangular number less than or equal to $N$, which gives us the value $m+n$. The difference between this triangular number and $N$ gives us $n$, which we can then subtract from $m+n$ to obtain $m$ as well. The following code is based on this algorithm:

+[->+>+<<]>[-<+>]>

[

>>+

[-<+<[-<]<[>]>>>]

<[->+<]

<

]

>>-

[-<+<+>>]<<[->>+<<]>

[

-<+

[-<+<->>]

<[->+<]>>

]

<<<-[->+>-<<]

>>[-<<+>>]>>[-]<<<<

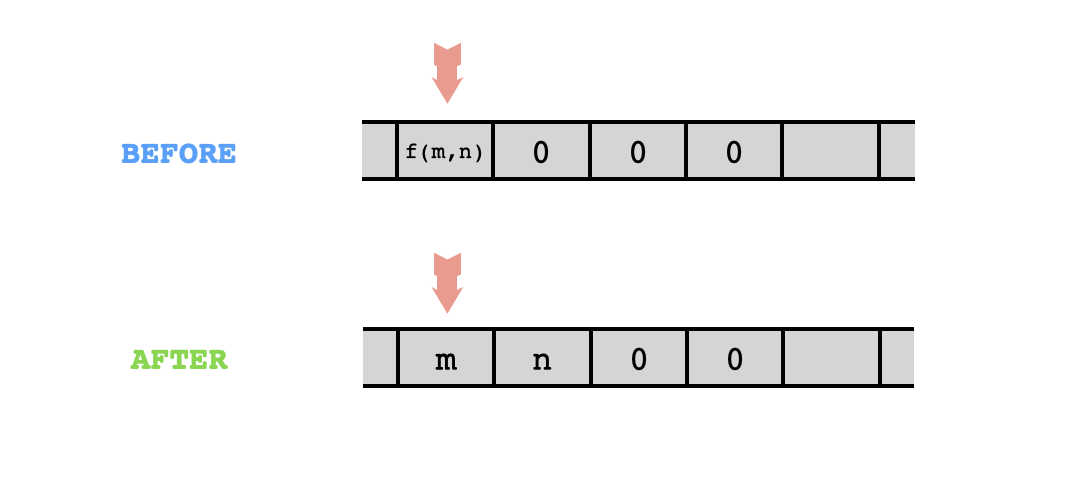

It requires $5$ cells of memory, including one cell containing the original number and four additional cells to be used as "scratch space", and acts like this:

The compression algorithm runs in $\Theta(M^2)$ time, where $M$ is the maximum of the two numbers, and the decompression algorithm runs in $\Theta(N\sqrt N)$ time, where $N$ is the value of the number to be decompressed. (Alternatively, the decompression algorithm is $\Theta(M^3)$ time, where $M$ is the largest of the two numbers compressed into $N$.) As a matter of fact, the "faster movement" algorithm that I included earlier in this post without explanation is based on the same idea as this decompression algorithm. It works by essentially "decompressing" the natural number to be moved into two much smaller natural numbers, and then moving each of those two using the less efficient naive method.

By iterating the above compression/decompression technique, we can compress an arbitrary number of different natural number values into a single cell. We can even compress arbitrary-length finite lists of natural number values into a single value. The caveat is that this doesn't actually do much for us in practice, since repeated compression via the above technique gives rise to astronomically large numbers. (The size of the compressed value may grow double-exponentially in the number of values being compressed.) Despite this, the fact that we can accomplish this is still at least philosophically interesting.