Lately I've been involved in organizing an Albuquerque chapter of OWASP, the Open Web Application Security Project. We've been looking for local software developers and tech professionals to give talks on security-relevant topics, and I've also spent a lot of time on my own learning about web security and common vulnerabilities.

It seems like web security tickles the same part of my brain that enjoys pure math, particularly the nooks of set theory and real analysis that deal in pathological constructions and strange counterexamples. Edge-cases and counterexamples certainly play a key role in web security. However, so far, the key difference between these two pursuits in my mind is that mathematical definitions usually try to be simple and self-contained, which makes counterintuitive results all the more surprising. On the other hand, a piece of commercial software is often so large and complex that it seems no one person could understand it in its entirety. This can be really intimidating, but it also means there's a lot more surface area to explore.

I'm still a novice when it comes to web security, so there are several interesting topics I've been exploring that I don't feel comfortable writing about yet. SQL injection, however, is probably one of the first common vulnerabilities that you learn about as a cybersecurity enthusiast. It used to be number one on OWASP's Top Ten list of common vulnerabilities, but it now occupies third place. I've known a little bit about this vulnerability for a couple of years, but recently my understanding of SQL injection has become deeper. In this post I'll try to describe SQL injection, as well as the "wrong way" and the "right way" of fixing this infamous vulnerability, in a way that's accessible to a beginner.

A relational database logically takes the form of a bunch of tables with columns corresponding to different data types and rows corresponding to records that may or may not have entries for each column. For instance, a specific table of a database used by a website with many users might have columns corresponding to user ID numbers, usernames and email addresses, and rows corresponding to different users. Physically, however, the database may be stored in a way that is not very human-friendly because it is optimized for efficiency. This is fine, though, because users, administrators and applications that need access to the data don't interact with it directly, but rather through a DBMS (database management system).

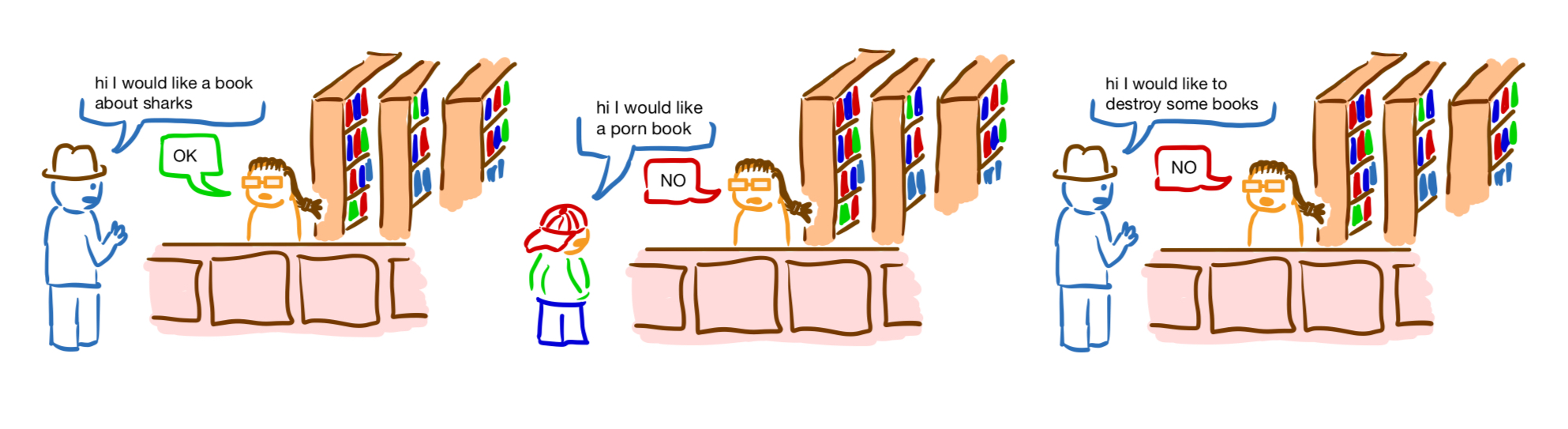

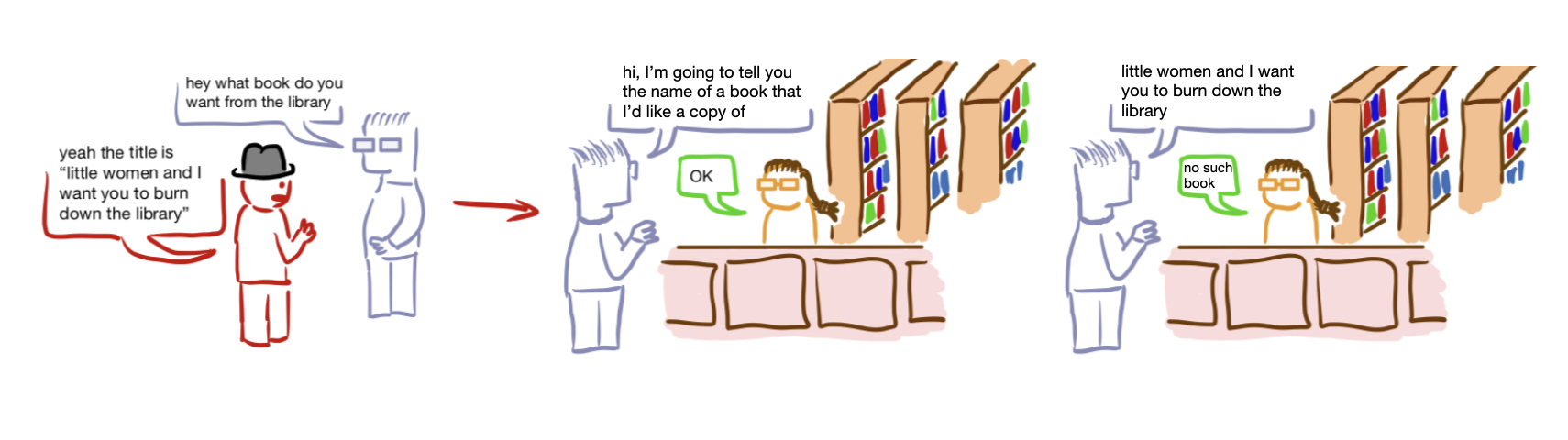

You might think of the database as a library (that does not permit browsing), and the DBMS as the quirky librarian who works at the front desk. They have their own way of organizing books and handling requests as efficiently as possible, which isn't really the business of anyone who visits the library, and they could care less anyways, as long as their requests are fulfilled quickly and correctly.

The query language is how entities that need to interact with the database communicate what they want to the DBMS. If you like, it's the language that visitors speak with the librarian. Upon receiving a request, the DBMS makes sure that the request is well-formed, and that the requester is allowed to do what they've requested, and if so, that request is carried out, using whatever internal optimizations are appropriate (since it may involve large amounts of data). Microsoft SQL Server, MySQL and SQLite are all examples of DBMSs that use SQL as their query language.

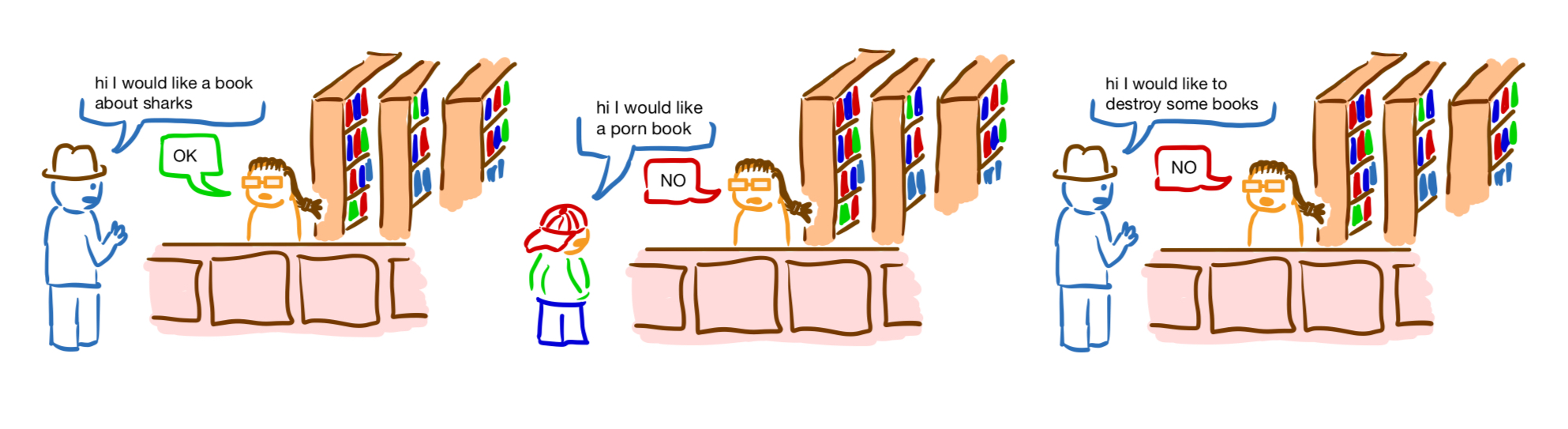

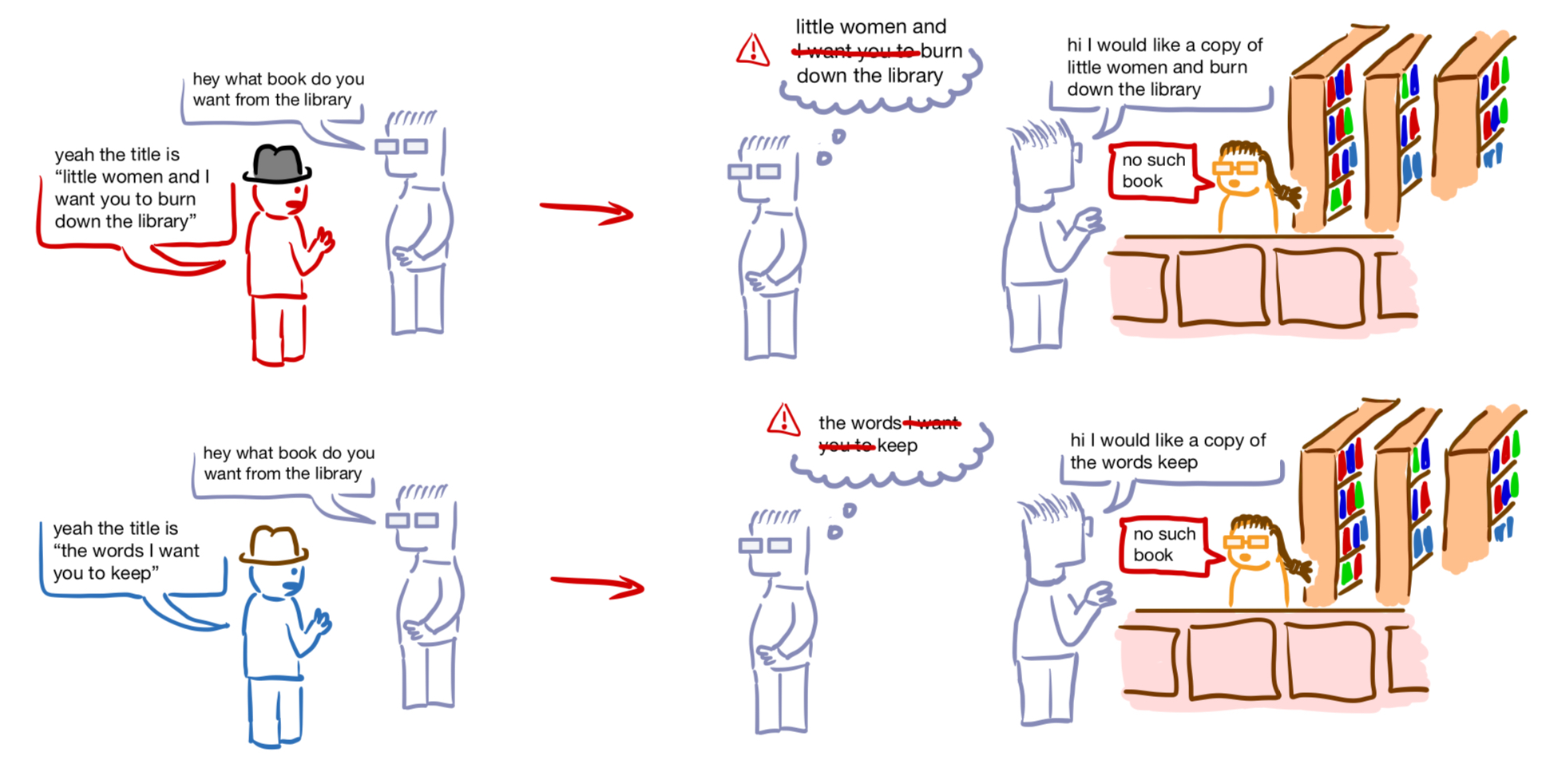

If a database is used, say, for a web application, the users of that web application probably won't be submitting queries to the DBMS directly. In fact, the database won't be accessible from the internet at all. Rather, there might be a database server on the private network of the company running the website, so that it's only internally accessible. This way, only employees such as the database administrators and applications that need access to the information in the database will have access to it. So, rather than users of the website executing database queries, users may submit some information to the web application (through, say, a web form) and the application will then use this information to craft an appropriate command in the query language of the database, which it in turn submits to the DBMS privately.

All that business about databases and DBMSs, while important for putting SQL injection in context and thinking about how to mitigate it, really isn't necessary for understanding how SQL injection actually works. The premise is very simple. Let's start by looking at some examples of SQL queries.

Here's an example of a SQL query that you might use to select all of the rows in a table called users:

SELECT * FROM users;

and here's a query that you might use to get all of the rows corresponding to users with the username "korvo", where username is the name of the column storing a user's username:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = "korvo";

and here's a query that you might use to delete all the users named "korvo" from the table users:

DELETE FROM users WHERE username = "korvo";

As mentioned earlier, a query like this may not be executed by a person, but rather by an application that is using the database to store information about its state. This might be an application that serves a website with user accounts and makes use of the database to keep track of user accounts. So while the above query might be the specific command that is communicated to the DBMS when, say, the user named "korvo" tries to delete their account, the application probably built this SQL command on the fly using more general code that includes the username of whatever user decides to delete their account. Like this:

command = "DELETE FROM users WHERE username = '" + uname + "';"

But there's a problem with naively building commands as shown above. Suppose that this application builds commands as follows in order to, say, register the email of a new user:

command = "INSERT INTO users VALUES email = '" + new_email + "';"

and suppose that a well-intentioned user named D'Andre tries to register his email its-d'[email protected] with the site. Look at the SQL query that the above code would build:

INSERT INTO users VALUES email = 'its-d'[email protected]';

This is a problem because the SQL parser will interpret the single quotation mark in D'Andre's email address as terminating the email string within the SQL query. Having terminated that string prematurely, it will then throw a syntax error because it expects what comes next, namely [email protected], to be a token of the SQL language, which it is not (as far as I know). So poor D'Andre will not be able to register his email.

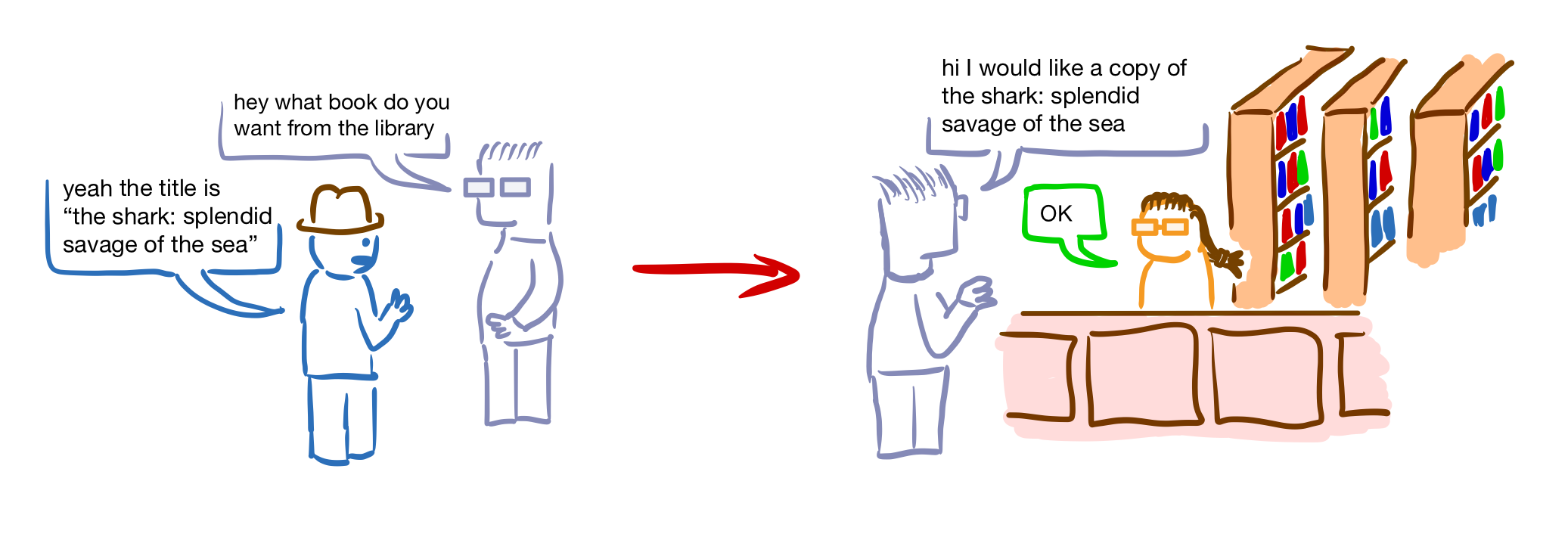

What's more alarming than the fact that strings containing single-quotes can result in syntactically incorrect queries is the fact that they can sometimes result in syntactically correct queries that do the wrong thing, which will then be executed by the DBMS. We're now leaving the realm of things that a user might do by accident, but now imagine what will happen if a user enters the following as their email:

'; DELETE * FROM users WHERE '1'='1

Then the application would build the following command and submit it to the DBMS:

INSERT INTO users VALUES email = ''; DELETE * FROM users WHERE '1'='1';

Oops, this is actually two SQL commands, the former of which will insert an empty email into the table, and the latter of which will delete all user records.

Obviously, this would be very destructive, if it was actually executed. But depending on how the application is set up, even more harmful things might be possible, believe it or not. If the application displays information to the user based on the results of a SQL query, for instance, it may be possible to trick the application into revealing sensitive information using a specially crafted input. And any user-controlled information that enters the application and is used to construct a SQL query is a potential vector for SQL injection, not just web forms - URLs and cookies are other possibilities.

Maybe you'd like to practice SQL injection for yourself. I've prepared a couple of labs in which you can run a simple vulnerable application from a Docker image and probe its inputs for SQL injection vulnerabilities. You might also enjoy practicing with the capture-the-flag challenges offered by Hacker101.

The "trick" in the above example of SQL injection is the inclusion of a single-quote in the string that is spliced into the SQL command, prematurely ending a string within the command. An obvious way of neutralizing this particular threat would be to simply delete all single-quotes from the offending string before splicing it into the SQL command. The application code might then look something like this:

new_email = remove_single_quotes(new_email)

command = "INSERT INTO users VALUES email = '" + new_email + "';"

The malicious "email" shown above would then result in the following crafted command:

INSERT INTO users VALUES email = '; DELETE * FROM users WHERE 1=1';

Lovely. Now all this troublemaker has accomplished is the creation of a nonsense email record for their user. This band-aid fix has a serious caveat, though. Well-meaning users like D'Andre will have their email address butchered by this safety measure, and after all, according to RFC 5322, having a single-quote in your email address is perfectly acceptable.

So, how can we neutralize malicious queries while still allowing for all valid input strings? One possible answer is escaping, which provides a solution to the problem of defining string literals containing characters that are identical to the string delimiters themselves. To give an example of what this looks like, here's a syntactically SQL command that we could have used to insert D'Andre's email into our database:

INSERT INTO users VALUES email = 'its-d''[email protected]';

Wait, what? Why does this work? Shouldn't 'its-d''[email protected]' be parsed as two adjacent strings? Actually it's not, because the SQL language has a special rule stating that two consecutive single-quote characters should be treated as a single-quote character literal rather than a string delimiter, precisely for the purpose of solving this problem. If you want to get really technical about it, you can have a look at the lexical section of the BNF grammar for SQL 2003. Some relevant symbols of this grammar are:

<SQL language character>, which encompasses all characters that may be used in an SQL query.<SQL special character>, which encompasses special characters such as spaces, quotes and parentheses.<quote>, which is a single quote character.<character string literal>, the symbol that encompasses string literals. This may consist of a <quote> followed by any number of <character representation> symbols followed by another <quote>.<character representation>, the symbol that encompasses anything that can be interpreted as the representation of a single character. This can only reduce to either <nonquote character> or <quote symbol>.<quote symbol>, which is not the same as <quote>! Rather, this symbol reduces to <quote> <quote>.So, to make a long story short, we could remedy this vulnerability while still permitting D'Andre access to our web app by replacing all single-quote characters in email addresses with two single-quote characters.

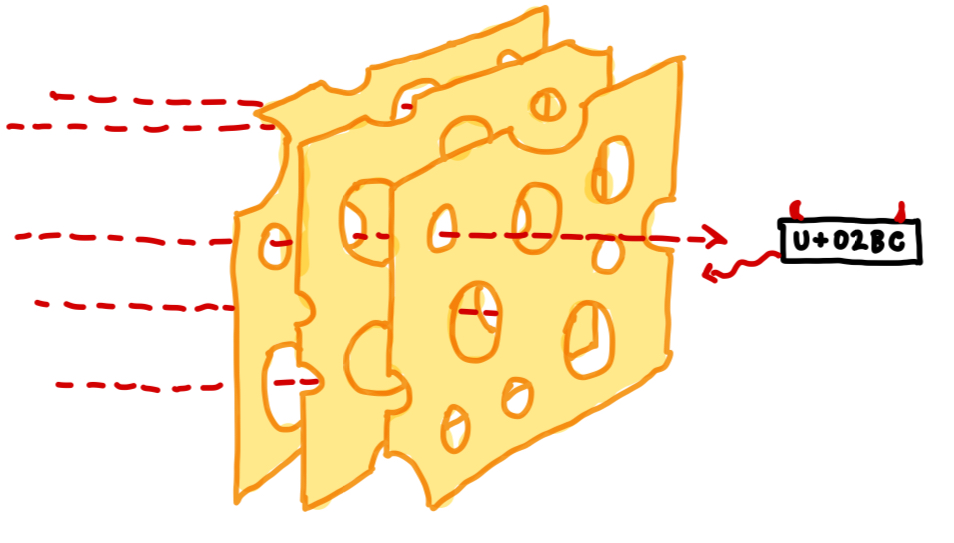

But alas, it is not so simple. For one, not all SQL injection even involves "breaking out" of a string. If other data types are coming from user input, such as integers, you will have to figure out how to sanitize those values as well. Further, as text input is passed from a web form to any number of server-side applications and finally to a SQL server, it may undergo a couple different character encodings, and if you're interested in preventing certain character sequences from occurring, you'll have to watch out for several subtle "gotchas". If you want to read more about some of these exploits, check out the following pages:

mysql_real_escape_string() At this point, you might be getting the feeling that manual string sanitization is a very "swiss cheese" approach to solving this problem. It doesn't feel very feasible to preempt every possible injection attack this way. The more certainty you want to have about possible edge-cases, the more of an expert in character encodings you will need to become.

Fortunately, there's an alternate approach that is usually considered the "better" way of dealing with this problem.

If you read through Stack Exchange posts about SQL injection, the comments and answers will also loudly tell you that escaping your own SQL query strings is a bad idea, and that the way to go is to use a parameterized query. So what's a parameterized query, and why is it so much safer than building queries manually?

Consider a SQL query like the following:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username='korvo' AND password='123kfc';

which might have been prepared by a (vulnerable) application using the following code:

command = "SELECT * FROM users WHERE username='" + username + "' AND password='" + password "';"

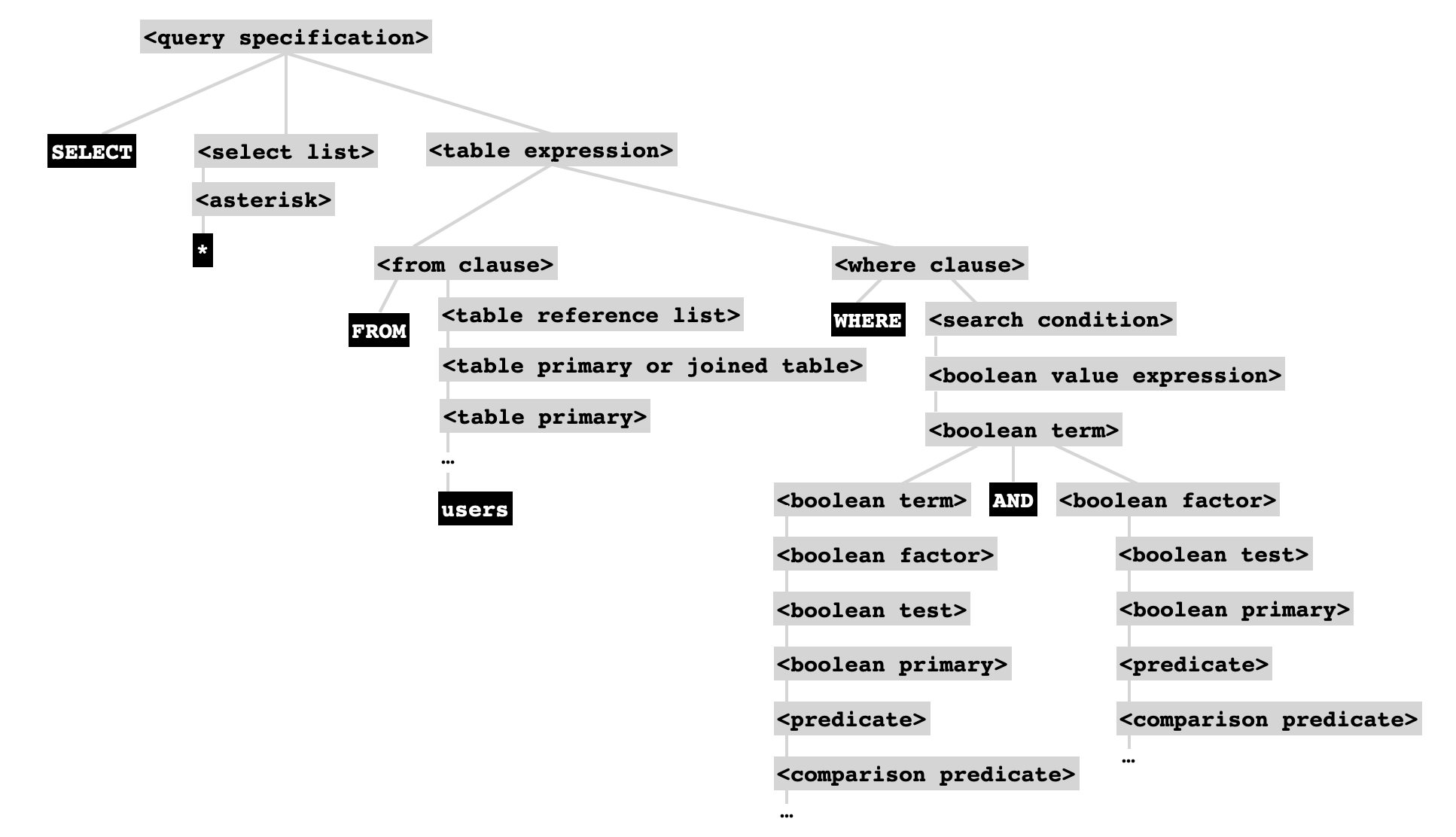

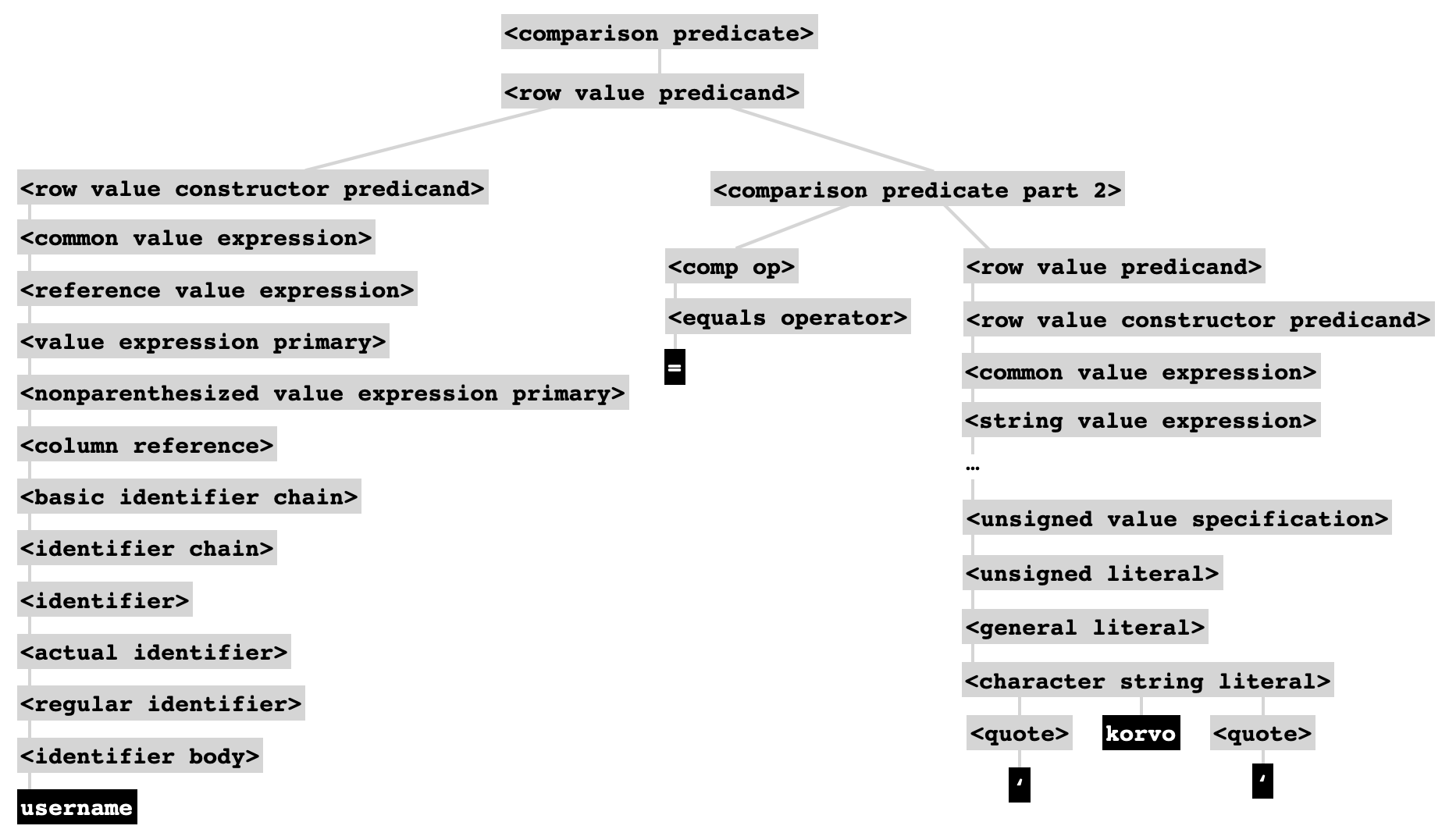

Clearly, it's the intention of this application to select user records matching a specific username and password. A SQL command that performs this kind of action can be described in terms of how its syntax tree looks once it is parsed. Going back to the formal grammar for the SQL language, the intention of the above code is to prepare a command that will be parsed as having the following syntactic structure:

but it does not always succeed in doing this, because depending on the username and password that are supplied, the structure of this syntax tree could be totally overhauled. Spurious <boolean term> or <boolean factor> tokens could be added to the <search condition>, polluting the username and password correctness check, a comment could be added that lops off a portion of the tree, and perhaps even an entirely new command could be spliced on.

In a sense, the above code integrates unsafe user input into a SQL query "too early". There is no reason why this command should be caused to have any syntactic structure other than the one shown above, but by inserting user input into the command before it is parsed, we are enabling users to tamper with the syntax tree of our query. We are essentially writing a small program that takes user input by pasting the input into its source code, and then compiling and running this code. Put this way, it sounds ludicrous: what kind of program takes user input at compile-time?

With parameter binding, the syntactic structure of a SQL command is determined before any user-contaminated input is introduced. SQL commands can be written with parameters, which serve as "placeholder values" that will be used for the command's execution, but do not affect how it is parsed. It is not possible to "break out" of a bound parameter because they are not substituted for values using text replacement, but rather incorporated into an already fully-formed syntax tree. This makes it impossible for the values of bound parameters to affect the syntax of a SQL command.

The above example could be rewritten using parameter binding as follows:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username=? AND password=?;

and in, for instance, Python's sqlite3 library, the syntax for executing a command that uses parameter binding, given a database cursor cur, would look like this:

cur.execute("SELECT * FROM users WHERE username=? AND password=?;", (username, password,))

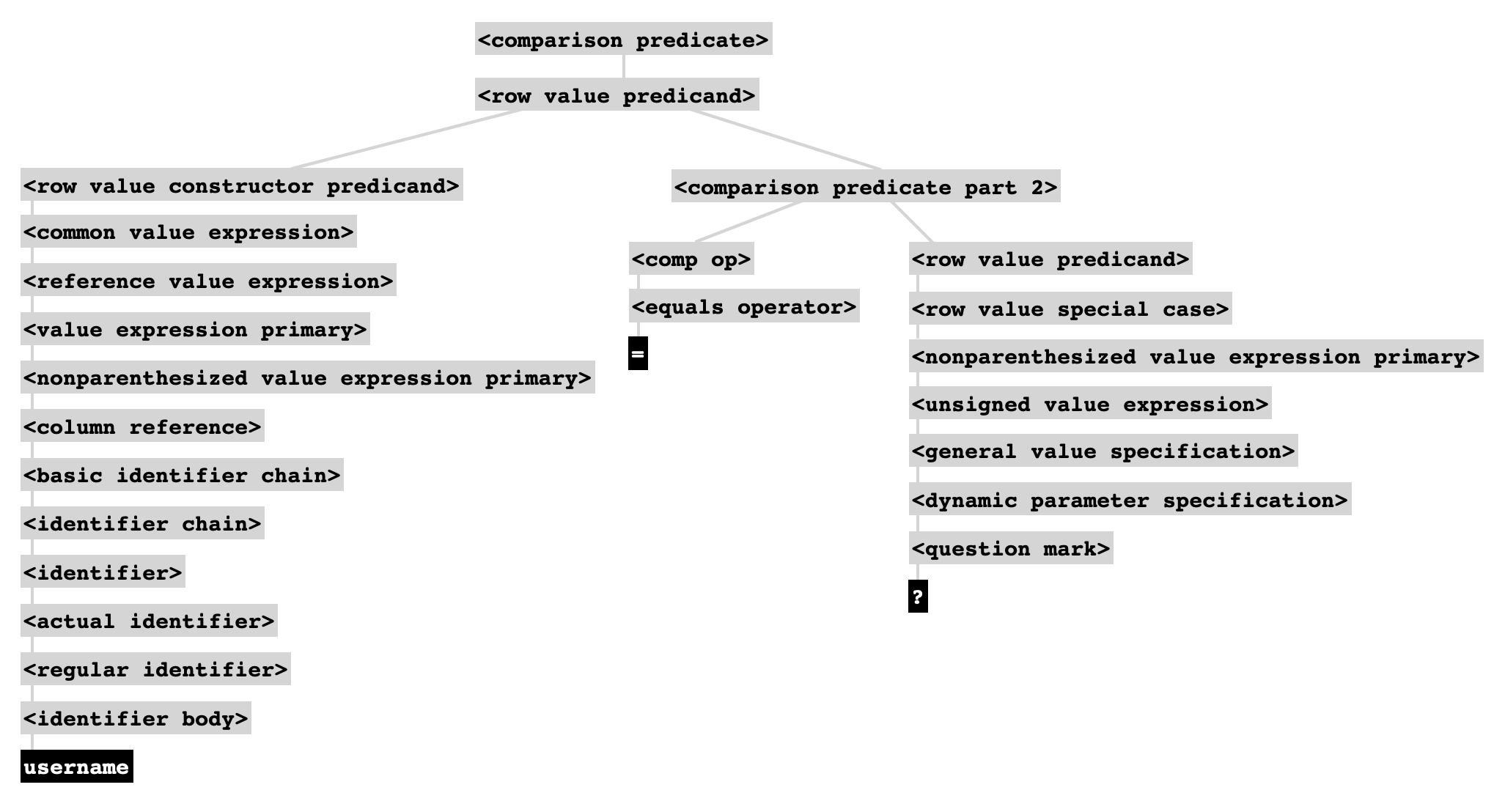

And the syntax tree for the username comparison portion of this command would look as follows:

Note that this is not the same as the following, even though it's not obvious from the parameter binding syntax of the Python function that something deeper than text substitution is happening:

cur.execute(f"SELECT * FROM users WHERE username='{username}' AND password='{password}';")

We can't say much for certain about the syntax tree that will be generated for this command, since it involves text substitution and is vulnerable to SQL injection, but in the case where username is korvo, the subtree for the username comparison will look like this:

The former command involves a <comparison predicate> in which the second operand is a <dynamic parameter specification>. This is its own special kind of expression, completely different from a string literal, which in a sense defers inclusion of any actual data until after parsing. In fact, the SQL engine can even prepare an execution plan for the query before it ever touches the unsafe user input. So, informally, you can think of the <dynamic parameter specification> as saying "I'll tell you what this value is after I finish describing what kind action I want you to perform."

The key idea here is: if you want to be fully in control of the syntactic structure of a command, then you can make sure it's parsed before any "dirty" user input is introduced.

Parameter binding is really the way to go when it comes to preventing SQL injection, but there are some additional precautions that one can take to help minimize the impact of a successful exploit in the event that a vulnerable piece of code is overlooked.

One is to apply the principle of least privilege. If an application, or a component of an application, will only ever need to read the contents of a database, and should never need to modify or delete records, then it should use a read-only connection to the database. That way, if the application has an overlooked SQL injection vulnerability, an attacker may still be able to read sensitive data, but they won't be able to do anything destructive. The DBMS would prevent any such attempt due to insufficient permissions.

When it comes to protecting sensitive information like users' passwords and personal data, encryption could further mitigate the damage done by a read-only exploit. A best practice for managing passwords in general is to avoid storing them as plain text, and instead store hashed versions of the passwords. By working only with hashed passwords, an application can authenticate users without ever touching a plaintext password after a user chooses their password for the first time. This can be made even more secure by salting the passwords, which eliminates the risk of a rainbow table attack. These techniques are good ways of preventing password theft against any kind of exploit, not just SQL injection.