In this short post, I'd just like to share a little puzzle that I assigned as an exericse while TAing for a functional programming class last spring. It's a cute problem, but it haunts me. It's the kind of problem that still keeps me up at night, months after I've solved it.

Here's the puzzle, stated in four different languages:

Lambda calculus: Can you write the function $\lambda hgfx. ~ h(g(f(x)))$ purely in terms of $c = \lambda gfx. ~ g(f(x))$? That is, can you define three-fold composition purely in terms of two-fold composition?

Haskell: Given the function

c = \g f x -> g (f x), can you write an expression using only the symbolcand open- and close-parens (and whitespace) that evaluates to a function with the same behavior as\h g f x -> h (g (f x))?Scheme: Given the function

c = (lambda (g) (lambda (f) (lambda (x) (g (f x))))), can you write an expression using only the symbolcand open- and close-parens (and whitespace) that evaluates to a function with the same behavior as(lambda (h) (lambda (g) (lambda (f) (lambda (x) (h (g (f x)))))))?Javascript: Given the function

c = (g) => (f) => (x) => g(f(x)), can you write an expression using only the symbolcand open- and close-parens (and whitespace) that evaluates to a function with the same behavior as(h) => (g) => (f) => (x) => h(g(f(x)))?

Below is a more thorough explanation.

In Javascript, the following function can be used to compose two functions:

function compose2(g, f) {

return function (x) {

return g(f(x))

}

}

or, if you prefer, using anonymous functon notation:

compose2 = (g, f) => (x) => g(f(x))

So, for instance, if $g,f$ were the functions defined by $f(x) = x+1$ and $g(x)=3x$, then $\texttt{compose2}(g,f)$ would be the function mapping its argument $x$ to $3x+3$.

But we can also define a curried version of the composition function, like this:

curried_compose2 = (g) => (f) => (x) => g(f(x))

So, if $g,f$ were as in the previous example, then $\texttt{curried-compose2}(g)$ would itself be a function, which accepts a function as its argument and returns that function composed with $g$. This function, when evaluated at $f$, yields the function mapping $x\mapsto 3x+3$. You can read more about currying here.

We can similarly write a function for composing three functions rather than just two:

function compose3(h, g, f) {

return function (x) {

return h(g(f(x)))

}

}

and in a similar vein, a curried variation of this triple-composition function:

curried_compose3 = (h) => (g) => (f) => (x) => h(g(f(x)))

The puzzle is as follows: to write curried_compose3 purely in terms of curried_compose2. To be precise, can you write an expression built entirely from curried_compose2, open parentheses ( and close parentheses ) that acts the same as the curried_compose3 function?

If you want to give the puzzle a try, you can use the little Javascript REPL embedded below. The two-function-compose has already been defined with the single-character name c. You can try out the little example from earlier by letting h = c((x) => 3*x)((x) => x+1), and checking that this function behaves just like (x) => 3*x+3. See if you can write an expression using only the three characters c, ( and ) that evaluates to a function with the same behavior as curried_compose3.

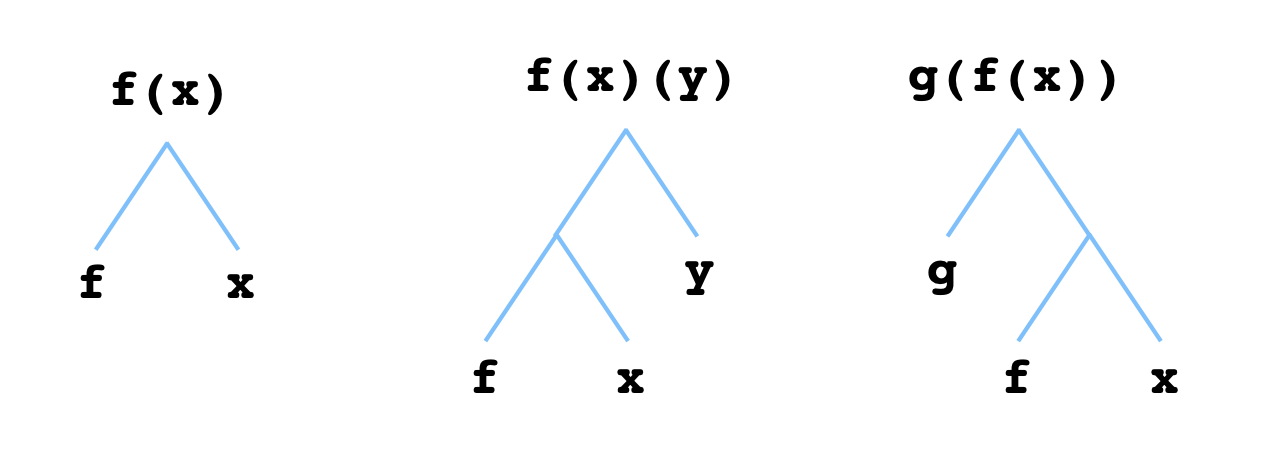

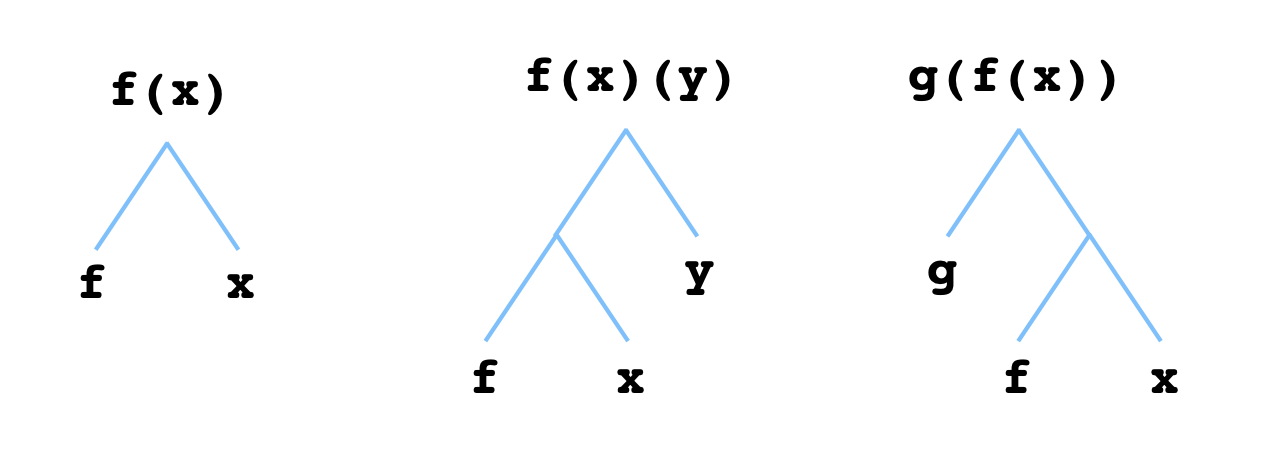

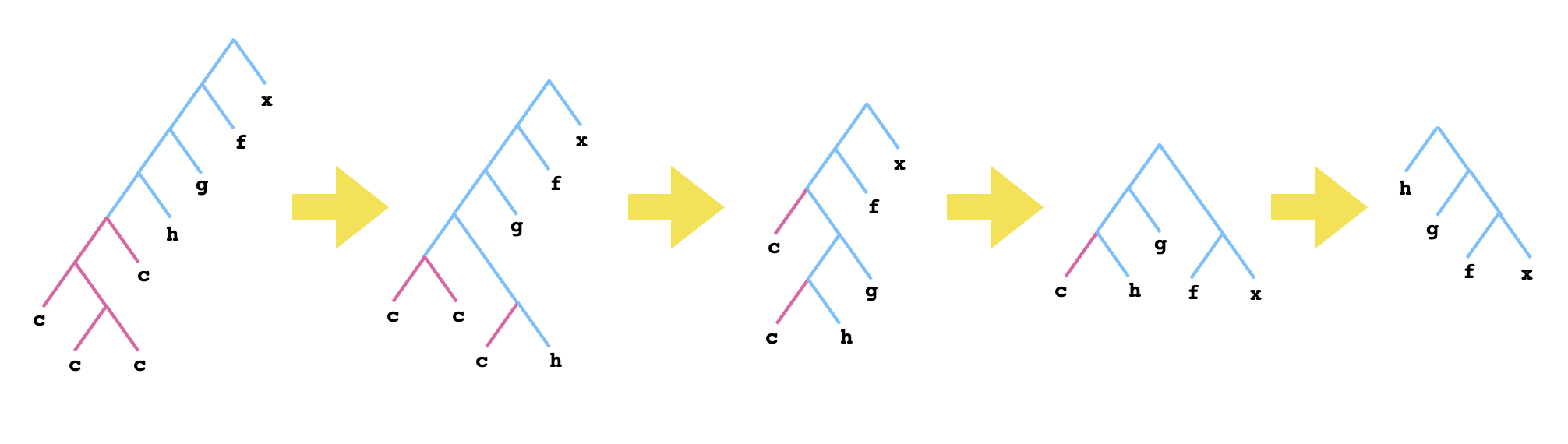

The way of reframing this problem that finally cracked it open for me was to think of expressions involving function evaluations as trees. Specifically, the expression f(x) would correspond to a tree with two leaves, with $f$ at the leaf on the left and $x$ at the leaf on the right:

We can then think of the composition function c as just a special kind of node that permits a specific kind of "tree rewriting":

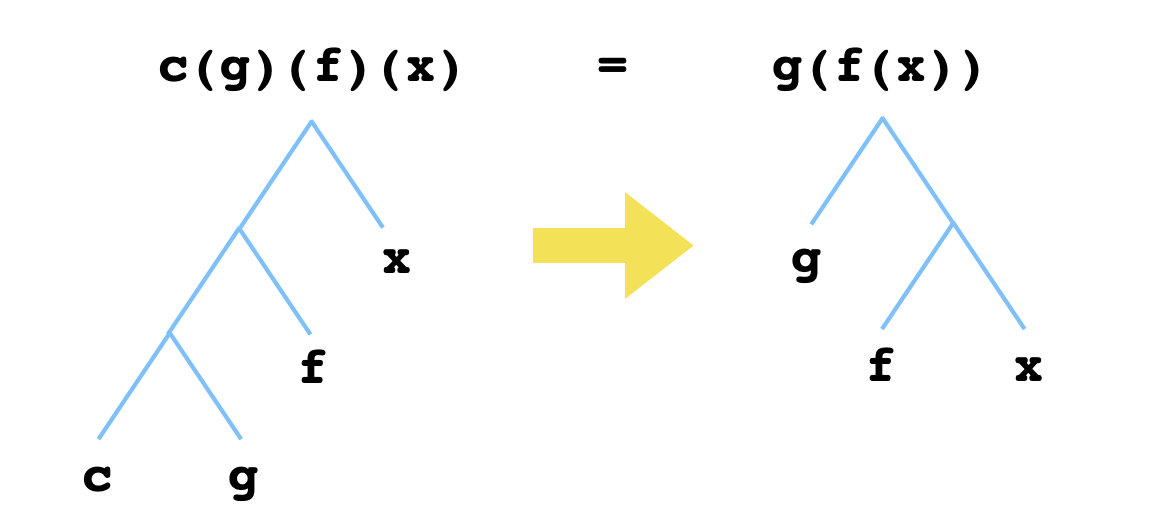

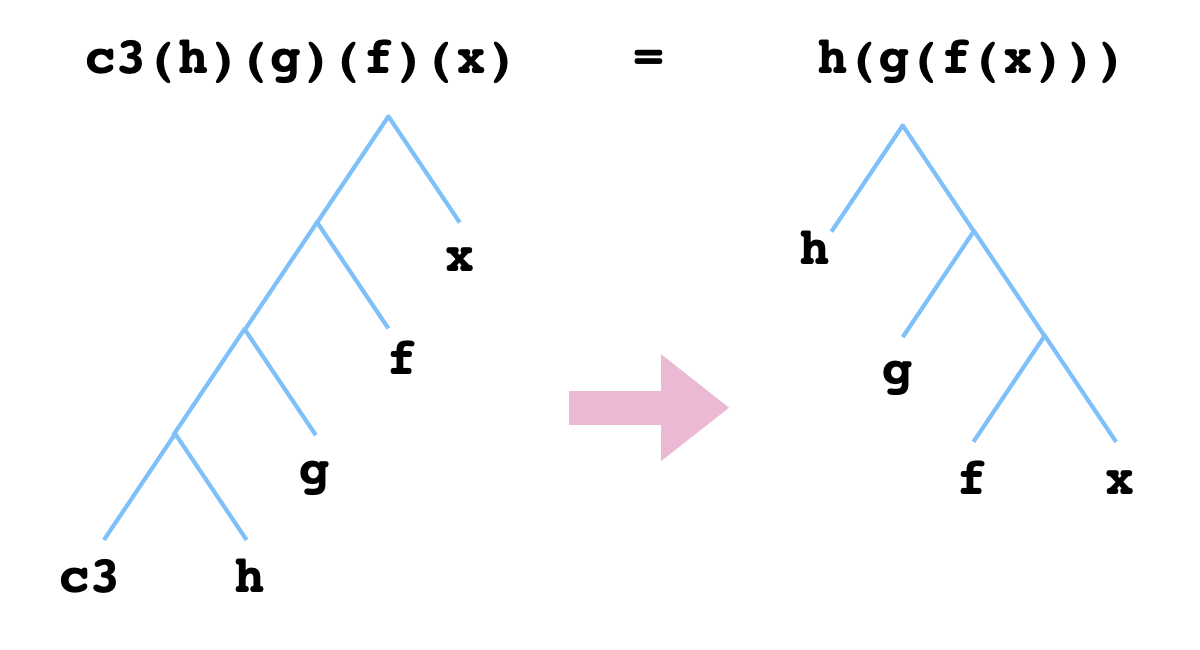

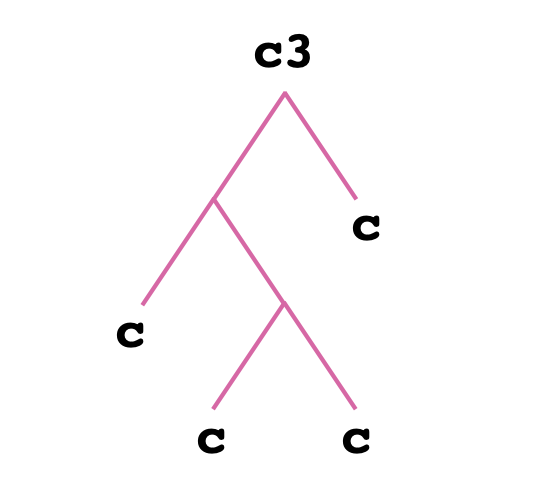

And given only this, we are tasked with constructing a tree c3 "built from" c, that is, a tree whose nodes contain c, that permits the following transformation:

Once I had reformulated the problem in these terms, it didn't take long for me to find a solution. It's hard to say what exactly about this paradigm made the problem so much easier for me to solve. Maybe it's just because drawing trees is more convenient than keeping track of a bunch of nested parentheses. In any case, I arrived at the following solution:

And we can check that it works correctly by repeatedly rewriting the tree for c3(h)(g)(f)(x) until we have eliminated all of the leaf nodes containing a c.

So, to sum up, here are the four solutions to the four different ways that we originally phrased the problem:

(c (c c)) c((c (c c)) c)c(c(c))(c)This solution still perplexes me. The strangest thing is that when I discarded all of my intuition about functions and composition, and turned this into a purely algebraic problem about rearranging binary trees according to a mechnical rewriting rule, it suddenly became much more manageable. The above solution is still pretty unintuitive to me, in the sense that I haven't found a way of ascribing meaning to it on a deeper level than "the algebra just works out". It's almost as if wanting a meaningful, intuitive solution prevented me from solving the problem. But maybe if I keep revisiting this problem, I'll eventually come up with an insight that completely unravels it, leaving the solution plain and transparent.

With that, I'd like to leave you with two more puzzles. First, can you generalize this to an n-fold composition function? That is, can you find a way of combining copies of the c function to form a function that accepts $n$ functions as (curried) arguments, and returns their composition? Secondly, can you convince yourself that the function (f) => (g) => (h) => (x) => h(g(f(x))), which composes three functions in reverse order, is impossible to write purely in terms of c?

Here's another Javascript REPL in case you'd like to mess around some more.