Recientemente he tenido que tramitar algunos datos físicos de tipo serie cronológica e investigar formas de medir la exactitud de un modelo que produce tales series. Una medida típica es la norma $\lVert \cdot\rVert_1$, con la que se puede cuantificar la "distancia" entre funciones reales $f,g$ así: Sucede que el modelo físico que estoy investigando produce a veces datos ligeramente retrasados temporalmente. Eso me ha animado a pensar un poco más teóricamente (aunque probablemente no importe mucho para ese proyecto) cuánto error puede surgir de translados pequeños. Es decir, si $T_\Delta$ representa el operador de translado: entonces ¿qué se puede decir sobre la distancia $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f\rVert_1$, cuando $\epsilon$ es un número real positivo y pequeñito?

Poco cuesta convencerse de que para la mayoría de funciones no patológicos, tanto funciones continuas como funciones escalonadas, la norma $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f\rVert_1$ disminuye linealmente como función de $\epsilon\to 0$. Pero precisamente ¿qué condiciones tiene que cumplir $f$ para que esto sea verdad?

He encontrado una condición suficiente en $f$ muy chula para que $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f\rVert_1 = \mathcal O(\epsilon)$ mientras que $\epsilon\to 0$: la variación acotada. Aquí me pongo a bosquejar una prueba y también presentar un ejemplo de una aplicación sin la propiedad de variación acotada para la cual $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f\rVert_1$ disminye más lentamente.

Primero demonstramos que cualquiera aplicación integrable $f:[0,1]\to \mathbb R$ con variación acotada cumple $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f\rVert_1 = \mathcal O(\epsilon)$. Para aclarar: en este dominio $[0,1]$ definimos el operador $T_\Delta$ de manera envolvente como si fuera el dominio un toro, es decir, definimos $T_\Delta f(x)$ como $T_\Delta f(x + \Delta \bmod 1)$. Así que, primero suponemos que $f:[0,1]\to \mathbb R$ es una función acotada, y que $B > 0$ sea una cota superior concreta en su variación.

Que sea $\epsilon \in (0, 1)$ arbitrario y que sea $2n$ el número entero par más grande para el cual $2n\epsilon < 1$. Como $f$ tiene variación acotada por hipótesis, también tiene que ser acotada, así que

Definimos ahora una función $\Delta(I,\epsilon)$ así, cuyos argumentos son un intervalo $I\subset [0,1]$ y un número real positivo pequeño $\epsilon > 0$:

Como antes, de la expresión $f(x+\epsilon)$ entendemos $f(x+\epsilon \bmod 1)$. Fíjate que esta expresión siempre le da a $\Delta(I,\epsilon)$ un valor finito como $f$ es acotada. Podemos derivar una cota mayor en $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f \rVert_1$ partiendo el intervalo de integración en muchas partes y expresando el valor máximo de $| T_\epsilon f - f|$ en cada subintervalo en términos de $\Delta$:

Que sea $\delta \ll 1/n$ (por ejemplo, $\delta = 1/n^2$) y que sea $x_0,x_1,\cdots, x_{2n-1}$ una serie de valores tales que $x_k\in k\epsilon + [0,\epsilon]$ y $|f(x_k + \epsilon) - f(x_k)| \geq \Delta(k\epsilon + [0,\epsilon], ~ \epsilon) - \delta$, pues tales valores tienen que existir debido a la definición de $\Delta$ como un supremo. Repartiendo la suma que aparece en nuestra cota superior en sus términos pares e impares, se tiene que:

Considerando primero la suma con los términos pares, se ve que

debido a la definición de la cota $B$ en la variación de $f$, junto con el hecho de que $x_0, x_0 + \epsilon, x_1, x_1 + \epsilon, \cdots$ es una sucesión creciente dentro del intervalo $[0,1]$. Semejantemente se puede derivar una cota superior para los términos impares. Sumando estas cotas se obtiene una cota en la suma entera:

Y pues como $\delta > 0$ podría haber sido arbitrariamente pequeña, se tiene también:

Entonces obtenemos una cota de $\mathcal O(\epsilon)$ en el integral que consideramos:

En cuanto a contraejemplos, no es muy difícil encontrar funciones que faltan la propiedad de variación acotada tales que $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f\rVert_\epsilon$ no es $\mathcal O(\epsilon)$. Considérate por ejemplo $f(x) = \log x$ o bien $f(x) = 1/\sqrt{x}$ para $x\in (0,1]$ junto con $f(0) = 0$. Cuesta un poco más encontrar contraejemplos continuos, pero se los puede hallar mediante una construcción parecida al seno del topólogo.

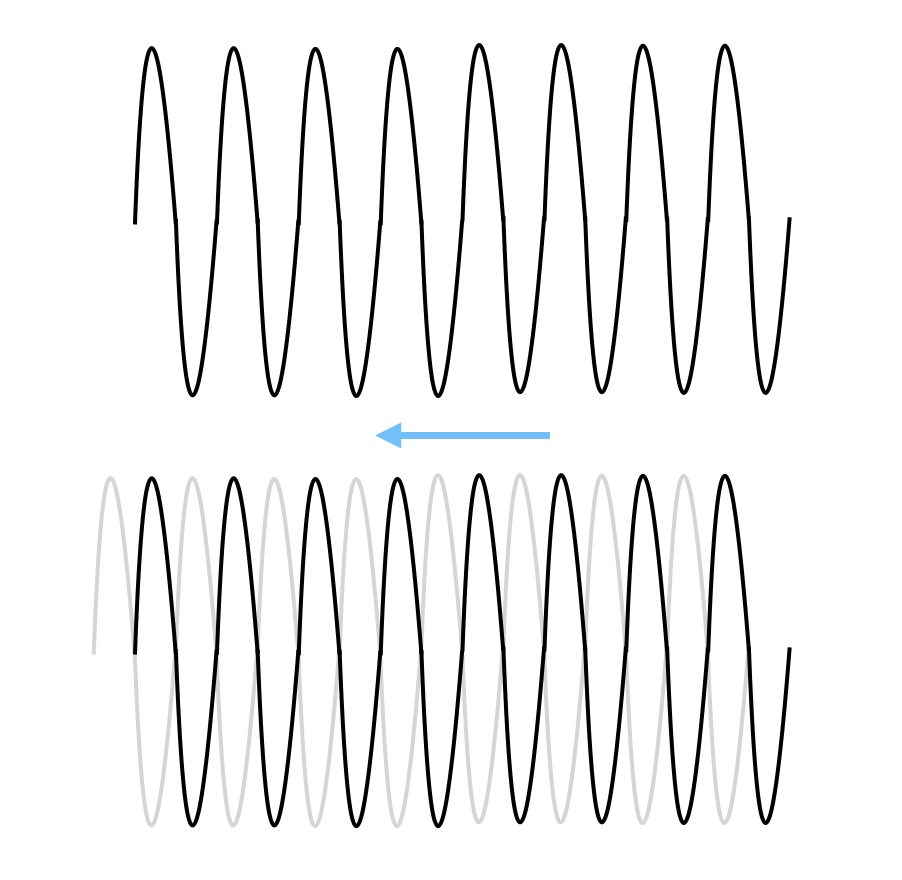

Define la aplicación $f:[0,1]\to\mathbb R$ por segmentos en una familia de intervalos $[0,1/2), [1/2,3/4), [3/4,7/8), \cdots$ de tamaño que disminuye geométricamente, tal que en cada intervalo $f$ es un sinusoide cuyo periodo parte su intervalo respectivo. Se puede asignarle al sinusoide número $n$ un número entero de periodos $N_n$ y una amplitud $a_n$, tal que para cada $n\in\mathbb N$, para todo $x\in [1-2^{n}, 1-2^{n+1})$. Una función así definida será continua siempre y cuando $a_n\to 0$ mientras que $n\to\infty$.

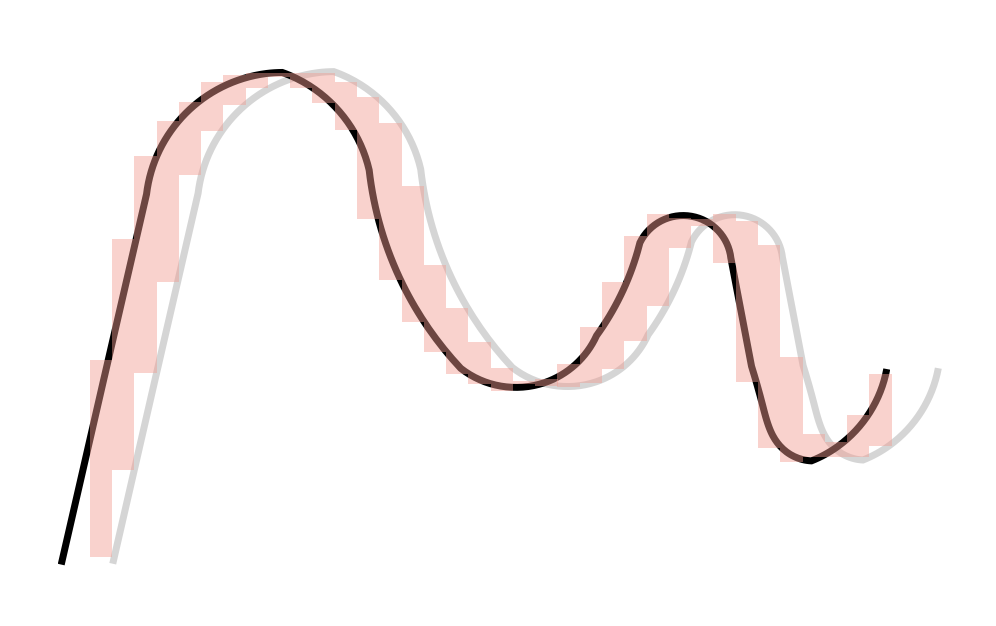

Dada esta definición, se ve que cuando se traslada $f$ por $\epsilon = (2^{n+1} N_n)^{-1}$, o sea medio periodo del sinusoide número $n$, se produce "interferencia destructiva" dentro del n-ésimo intervalo de tal manera que los puntos máximos de $y = f(x)$ y de $y = f(x + \epsilon)$ se desalinean.

Se puede demonstrar que la cota inferior siguiente vale para este valor fijo de $\epsilon$:

Si se define, por ejemplo, $a_n = 1/n$ y $N_n = n^2 2^n$, entonces $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f\rVert_1 = \Omega(\sqrt{\epsilon})$ según esta cota!

Todavía me quedan algunas preguntas no contestadas. ¿Es posible que $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f\rVert_1$ ni disminuya a $0$ mientras que $\epsilon\to 0$, siendo $f$ una aplicación continua? Aunque no es cierto para toda función integrable $f$ que $\lVert T_\epsilon f - f\rVert\to 0$ mientras que $\epsilon\to 0$, ¿tiene que ser $0$ un púnto límite de esta cantidad mientras $\epsilon\to 0$?