Integration without Antidifferentiation (Part 2)

2018 April 26

In this blog post, as I did in the precursor to this post, I will explore some more methods of evaluating a few recreational definite integrals without finding the antiderivatives of their integrands. The methods that I employ to solve these problems are, more or less, elementary, relying heavily on functional equations and basic properties of the integral rather than advanced techniques. shall begin with a list of problems that I will solve over the course of the post, so that the reader can try them first:

Evaluate the following integral expressions:

In reality, I will reveal very few distinct tricks in this post, but I will use each trick many times and generalize each as much as possible.

I will evaluate the integrals mostly in the order than I proposed them, beginning with the first one: Using a simple substitution $x\to -x$, we can see that this integral is equal to If we let $I$ be equal to the value of this integral, we can see that

Thus, we have $I=1$, and we have evaluated our first integral:

What a strange creature! Only in one's wildest dreams might the integrand have an elementary antiderivative, and yet we somehow managed to evaluate this definite integral. What allowed us to do this?

First of all, notice that when we made the seemingly innocent substitution $x\to -x$ at the beginning, the endpoints of the integral, $-\pi/2$ and $\pi/2$, were unchanged, since they are opposites of each other. They switched places upon making the substitution, but we were able to switch them back since the change from $dx$ to $-dx$ lent us a sign change that allowed us the change the direction of the integral, switching the endpoints back to how they originally were. The evenness of the cosine function left $\cos(x)$ unchanged as $x$ changed to $-x$, creating a similarity between the integrals before and after the substitution.

Now for the interesting part. When we changed $x$ to $-x$, the function changed to Thus, this function (let's call it $f$) has the cool property Notice that any function in the form has this property, as long as $O(x)$ is an odd function. In this case, the odd function used was $\sin(\sin(x))$. While this weird (or "odd") function served to make the integral seem much more complicated than it actually was, it really changed nothing about the method of evaluating the integral.

Having properly analyzed the integral, we are now ready to generalize. Consider now the integral where $a$ is a constant, $E$ is an even function, and $O$ is an odd function. By making the same substitution as last time, this integral is equal to and if we let $I$ be the value of the integral, we have and so we have the wonderful result

Now we can consider the next integral: Immediately, the reader should recognize this as a special case of the result that we have just derived, with $a=\infty$, $E(x)=e^{-x^2}$, and $O(x)=x^3$. Using the formula previously obtained, we have Finally, we have Did you see the Gaussian Integral show up in that derivation? If you don't know what I'm talking about, you should go back to the precursor to this post whose link I offered at the beginning of this post. In that post, I derive the "Gaussian Integral.

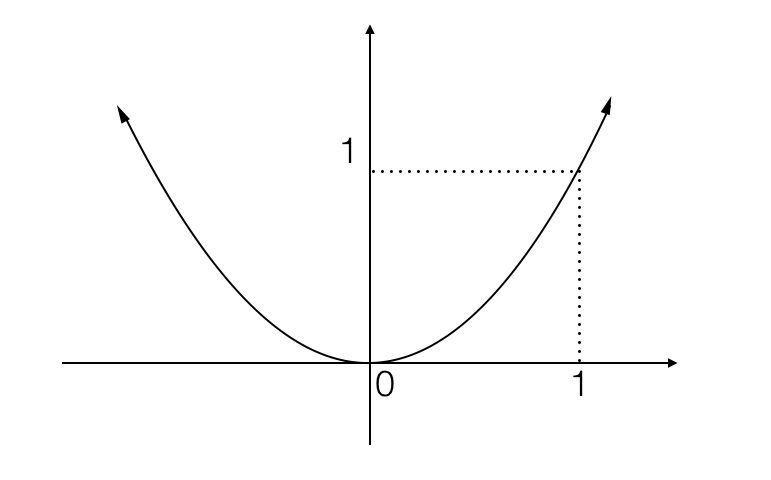

For the next two integrals, I will use the concept of an inverse function to evaluate them. First, consider As surprising as it may seem, there is actually a way to evaluate this integral using the geometric interpretation of an integral as area. Let us begin by splitting this integral up as follows: This may seem strange, but it will make sense momentarily. Consider the graph of $y=2^{x^2}-1$:

The first integral into which I split the original problem can be interpreted as the area underneath this curve:

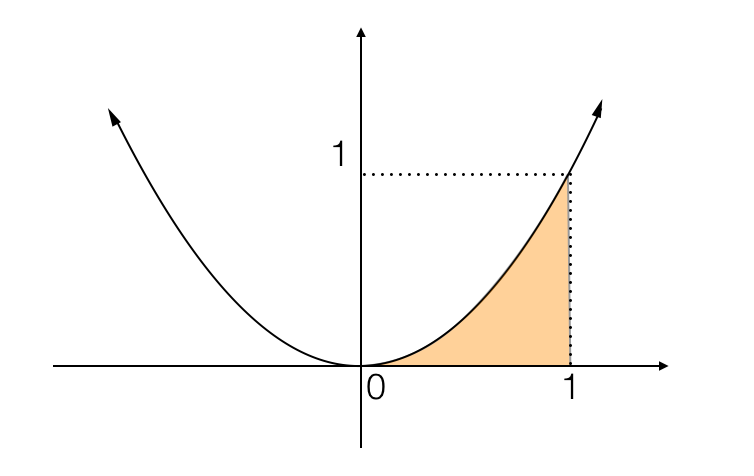

Get ready, here comes the trick. Recall that the graph of the inverse function of a function can be found by reflecting the original graph about the line $y=x$. Thus, the area found by integrating the inverse of a function is the area between the y-axis and the function, where the limits of the integral refer to $y$ values rather than $x$ values. Since the values of $2^{x^2}-1$ are $0$ and $1$ at $x=0$ and $x=1$ (that is, the function has fixed points at $x=0$ and $x=1$), and since $\sqrt{\log_2(x+1)}$ is its inverse, the second integral can be interpreted as the following area:

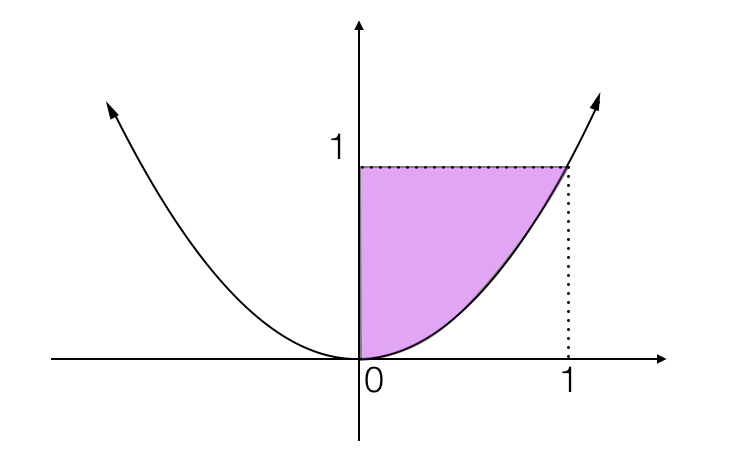

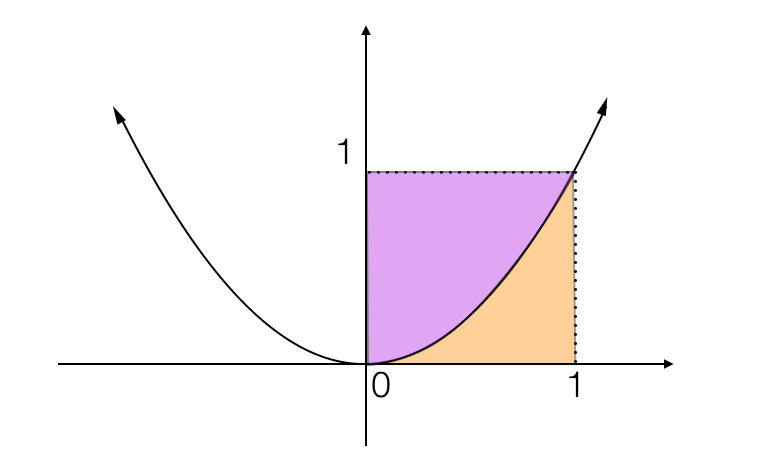

The sum of these two integrals gives the sum of the orange area and purple area, or the area formed by combining them:

...but this is just a square with side length $1$, and its area is clearly $1$! Thus, the sum of the first two integrals is $1$, and the whole expression into which we divided our original integral is equal to $2$. Thus, we have

Let's generalize this little trick. Suppose that $f$ is a bijective function with fixed points $a,b$ such that $f(a)=a$ and $f(b)=b$, with $a\lt b$. Then consider the integral Since the graph of $y=f^{-1}(x)$ is the reflection of the graph of $y=f(x)$ about the line $y=x$, we will always be able to put together the areas under $y=f(x)$ and $y=f^{-1}(x)$ like two puzzle pieces to obtain some rectangles whose areas we can easily find. In general, this area will always be given by which can be simplified to $b^2-a^2$. Thus, we have

Now we can move on to the next problem, which is a multi-integral expression:

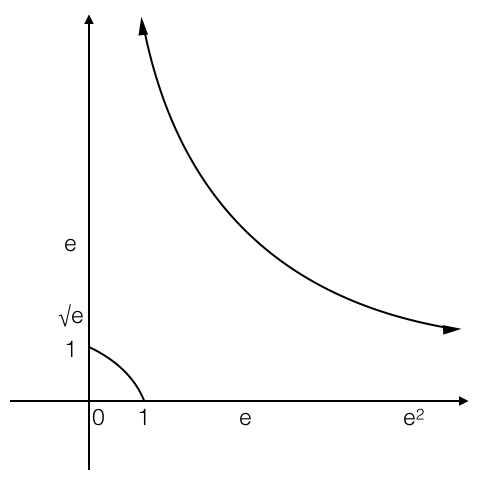

Again, notice that $f(x)=e^{1/\ln(x)}$ is a function that one could never hope to antidifferentiate. Let's graph the integrand just like we did last time, since that seemed to help. Using the special values $f(e)=e$, $f(e^2)=\sqrt e$, and $f(\sqrt e)=e^2$, I can make a graph:

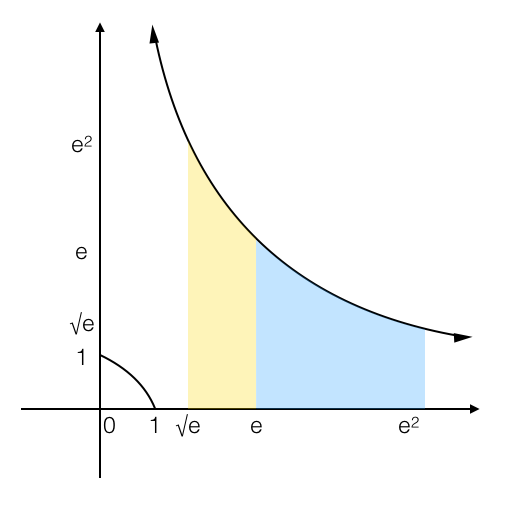

Using the interpretation of a definite integral as the area under a curve, I can display the areas represented by each of these two integrals:

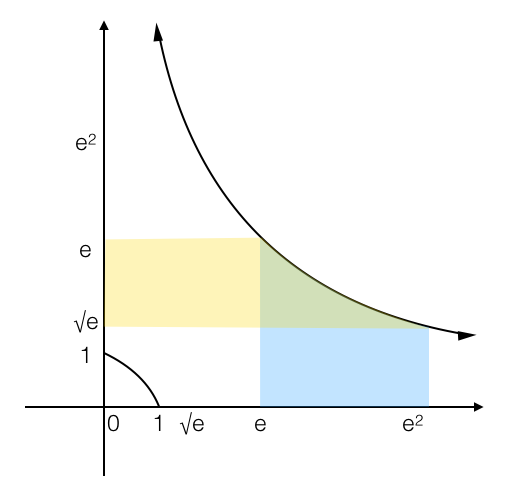

The integral expression that we wish to evaluate is equal to the difference of these two areas - more specifically, the blue area minus the yellow area. Now get ready, here comes the trick. Notice that the function $f(x)=e^{1/\ln(x)}$ is its own inverse (in math language, one would say that it is an involutory function). Because of the reflection property of inverse functions that I mentioned earlier, the graph of $y=f(x)$ must be symmetrical about the line $y=x$. If I reflect the yellow area about the line $y=x$, its area will remain unchanged, but look what happens when I do that:

Since I'm taking a difference of the two areas, and the green area is contained in both the blue and yellow areas, it will cancel out. Thus, we only need to find the area of the blue region on this graph minus the area of the yellow region. Need I point out that they're both rectangles, whose areas we can easily calculate? The side lengths of the blue rectangle are $e^2-e$ and $\sqrt e$, giving an area of $e^{5/2}-e^{3/2}$, and the side lengths of the yellow rectangle are $e-\sqrt e$ and $e$, giving an area of $e^{2}-e^{3/2}$. The difference of these two areas gives us our answer:

In general, one can prove that if $f$ is an involutory function, then

I'll omit this proof as an exercise for the reader... it's not too difficult.

Now I'll move on to the second-to-last integral problem (appropriately, it's a double integral). Unfortunately, my methods for evaluating this integral is a little bit less elementary. In my derivation of the solution, I will make use of the following two identities: ...which hold for any natural number $n$. Notice that, as I will use later, these two formulas imply that for any natural number $n$, Let us return now to the problem that I posed at the beginning: Recall that $\cos(x)$ has a Maclaurin series centered at $x=0$. Of course, we all know that the coefficients of this series are given by ...but, as I will demonstrate in a moment, we don't need to know the coefficients. So, for the sake of simplicity, I will instead write This series representation for $\cos(x)$, together with the identities that I mentioned earlier, causes the whole integral to unfold before our eyes: Which gives us the miraculous result Wasn't that awesome? Its generalization is even awesomer. Suppose now that $f(x)$ is a function with a Maclaurin series: If $k$ is some arbitrary constant, then we have the following:

Which gives us the following fantastic result:

Just remember that this only works if $f$ has a Maclaurin series. As an exercise, I propose the following problem for the reader: try to find a similar formula for or, more generally, for some arbitrary natural number $n$.

Now we can move on to the final integral, whose derivation is significantly similar than the previous one. The integral is To evaluate this integral, we need only recal the Maclaurin series for $e^x$ (whose coefficients we will actually have to use this time) and a few properties of complex numbers: Letting $x=e^{i\theta}$, we have or Taking the real part of both sides, we have and by integrating both sides from $0$ to $2\pi$, we have Notice now that for any natural number $n\gt 0$, Thus, we have and, finally,

That beautiful identity concludes this blog post!

CONTINUATION: Soon after finishing this post, I discovered another mind-blowing trick that absolutely deserves to be part of it, so I'm going to add it to the end.

Evaluate the following integral expressions:

Once again, you should definitely try your hand at these problems before you read my explained solutions.

Let's start with the first integral: Let us set the variable $I$ equal to the value of this integral. By using the substitution $x\to \sqrt{1-x^2}$, we have

This tells us that

Notice now that if we let $u=x-\sqrt{1-x^2}$, we have If we make this substitution $x-\sqrt{1-x^2}\to u$ into our integral, the endpoints at $0$ and $1$ will change to $-1$ and $1$, leaving us with ...and this is trivially evaluated, giving us the mysterious result

Did you catch the trick? I'll do the second integral so you have another chance to see it. Starting with I'll make the substitution $x\to \pi/2-x$, giving me the integral The original integral must be equal to the average of these two integrals, since it is equal to both. Thus, we have Making the substitution $x\to\sin(x)-\cos(x)$, we have and we have another interesting solution:

I've managed to generalize the trick used for these integrals, and I'll just give you the formula immediately and follow it with a proof. I assert that if $E$ is an even function, $\theta$ is an involutory function (like $\pi/2-x$ or $\sqrt{1-x^2}$), $f$ is some function, and $a$ is an arbitrary constant, then

and here is a proof, using the same method as before with the substitutions $x\to\theta(x)$ and $f(x)-f(\theta(x))\to x$:

...and this proof really does end my blog post (no continuations this time, I promise).