2017 Sept 5

Compute the following definite integrals:

In this post, I'm going to lay out a few tricks that one can use to evaluate the definite integral of a function over an interval without actually finding the antiderivative of the function. I'll start with the first integral, which is called the Gaussian Integral after the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss who famously evaluated it. The derivation of its value is rather complicated, and uses a few tricks that would be hard to come up with on the spot.

Before deriving its value, it would be best to recall an identity that is used in the derivation: This identity is rather apparent, and can be proven easily using the distributive property of multiplication over addition. And because a definite integral is a limit of a sum, we can usually extend the properties of sums to definite integrals, and say that

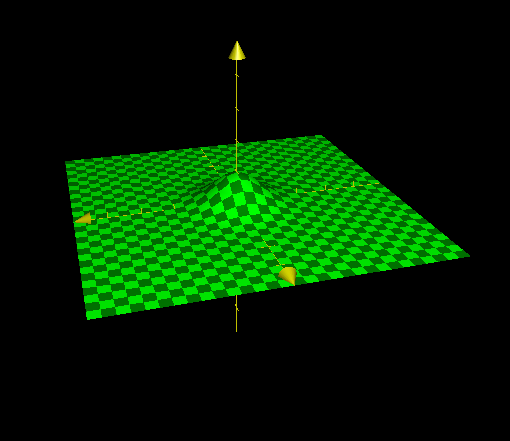

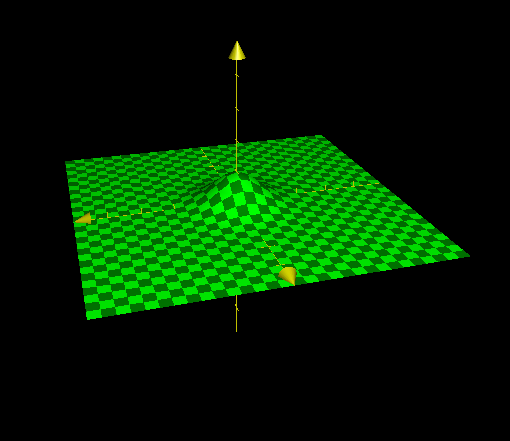

Now we may begin. We start by recognizing that the integral has a positive value since the graph of $e^{-x^2}$ is never dips below the $x$-axis, allowing us to say that it is equal to the square root of its own square: and because the variable used in the integration does not matter, we may swap the $x$ in one of the integrals with a $y$: Now we apply our sum identity to say that this is equal to This is where the tricky part comes in. The double integral underneath the radical can be interpreted as representing a volume between a three-dimensional curve and the $x,y$ plane in the three-dimensional cartesian coordinate space. The curve would be $z=e^{-(x^2+y^2)}$, and here is what it would look like:

When we find the volume underneath it using the double integral that we are currently using, it is as if we are taking an infinite number of mutually parallel vertical slices, finding the cross-sectional area of each, and adding them all up to come up with a volume. However, the volume could instead be found by a different method - instead of taking an infinite number of plane slices, imagine how the double integral would look if we instead took an infinite number of "cookie cutter" slices by adding up the areas on the sides of an infinite number of cylinders inscribed under the curve. Suppose we take a cookie cutter in the shape of a cylinder with radius $r$ and punch it into this curve, with the axis of the cylinder lined up with the $z$-axis. The cylindrical "cross section" that we obtain will be the same all around, because the function can be expressed directly as a function of $r$ rather than of $x$ and $y$ - since $r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}$, $z$ can instead be expressed as Which will be the height of our cylindrical cross-section. The radius of this cylindrical cross-section is $r$, so, since we now have the height of each cylinder, we can say that the surface area of each cylinder (excluding that of the bases) can be expressed as And since the area under the curve can be expressed as an infinite sum of infinitely many inscribed cylinders, with radius $r$ varying from $0$ to $\infty$, we can replace our double integral to get This integral is elementary to evaluate: Which is our final and beautiful answer.

Next up is the integral The trick used to solve this one is recognizing that This fact is easy to establish, and I will exclude the proof. If we substitute this into our original integral, we get Now we may make use of the property of double integrals that allows us the switch their order under "normal" circumstances: Now we may evaluate this double integral to get our answer. The innermost integral has an elementary antiderivative, which is given by Again, this can be easily derived using integration by parts, and I will exclude the proof. This tells us that and so our integral is transformed into and so we have found the value of our second integral.

The two most difficult integrals are now completed. The next two can be evaluated simply using algebraic manipulation, and require no actual integration whatsoever - one can primarily use the properties of the integral to evaluate them, rather than the properties of the function being integrated.

Let us set the variable $I$ equal to the value of our first integral: This may seem intimidating at first, but it is actually quite easy to discover the trick once one begins to play with it. If we decompose our function using partial fractions, we end up with Now if we make the substitution $x\to\frac{\pi}{2}-x$ in the integral, we have Now we can use the property of integrals to change our equation into Do you recognize how our original integral has appeared? We can replace it with $I$ and obtain Now we have a linear equation, which can be solved readily:

Now we may consider the next integral: Let us now define $J$ as follows: and with the substitution $x\to 2x$, we have If we make the substitution $x\to \frac{\pi}{2}-x$ in the second integral, using the "interval-flipping" property of integrals mentioned in the solution of the last integral, we have and because of the symmetry of the sine function, and so we are left with another linear equation: and so is our answer.

The next integral is where ${ }$ represents the "fractional part" function.

The trick here is recognizing that the fractional part function can be defined using a piecewise function as and utilizing the following property of integrals: Using our piecewise definition of the fractional part function, we can say that and using the integral identity, we can split up our original integral into or and since each integral covers a single interval of the piecewise definition of ${\ln x}$, we can change each integral to Now we may evaluate the integrals that we are summing: Which can be evaluated easily as a geometric series: And this is our final answer.