2017 June 24

Evaluate the following infinite series:

This post will address more difficult sums that do not telescope (at least, not easily enough for telescoping to be an efficient method of solving them) and will provide some alternate methods for evaluating them.

First we will deal with the well-know alternating harmonic series which, unlike the non-alternating harmonic series, converges. The trick in this case is to define a function $S(a)$ as follows: Note that the value of our sum is equal to $-S(-1)$. This will come in handy later. Look what happens when we differentiate $S(a)$: Look! This is a geometric series, and we know how to evaluate that using the formula for the sum of a geometric series. We can now antidifferentiate both sides to get By taking the case of $S(0)$, we can determine that the constant is $0$ and so Remember how we said that our sum is equal to $-S(-1)$? Now we can use our formula to say that the answer is

We can use a similar approach for the series We can define $S(a)$ this time as so that our sum is equal to $S(1)$. By differentiating, From the previous summation problem, we found out that So we can say that Then, by integrating, we get By observing the case of $S(0)$, we see that $C=0$ and so and now we can just evaluate it at $a=1$, right?

No. Not right. This function isn't exactly defined at $a=1$ because Whoa whoa whoa. What do we do now?

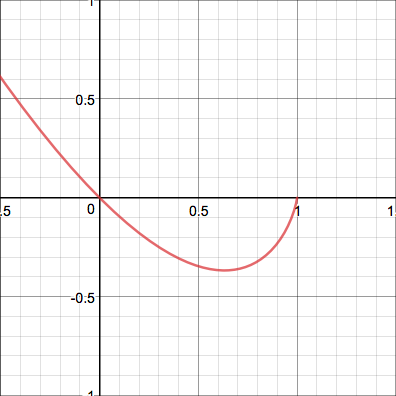

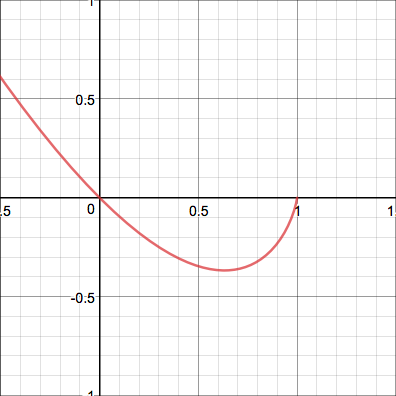

We have to take the limit of $S(a)$ as $a$ approaches $1$, rather than trying to interpret its value literally. since the $-(1+a)\ln(1+a)+2a$ is well-defined at $a=1$, we can change this to When we evaluate the limit, we get $0$ as the result. This result can be confirmed graphically by a plot of the graph $y=(1-x)\ln(1-x)$ near $x=1$:

Thus our answer is $2-2\ln(2)$, and so

Now for the series Let us again define a function $S(a)$: Note now that our sum is equal to $\frac{1}{2}S(\frac{1}{2})$.

Uh-oh. There's a problem. Look what happens if we differentiate this time: It gets more complicated! What do we do now?\

The problem was that we were doing things in the wrong order - this time, instead of differentiating first, we should integrate first. Look what happens if we do that: Look at that! Another geometric series. Now we can use the formula for the sum of a geometric series again to get The $-1$ was added because the sum is from $1$ to $\infty$, so it excludes the first term $a^0=1$ of the series. Now we can differentiate to get a closed-form formula for the sum: Which means that, since our sum is equal to $\frac{1}{2}S(\frac{1}{2})$, the answer is Which shows that

On to the next series: This is basically a more complicated version of the previous series, and can be solved in the same way. Again, let so that our sum is equal to $\frac{1}{4}S(\frac{1}{4})$. Now we can antidifferentiate to get then divide both sides by $a$ so that we can integrate again: Again we use the formula for the geometric series... again we differentiate both sides... multiply by $a$... differentiate yet again... and so And so

Onto the last summation problem. This one uses a strategy completely different from any of the others. This is a very strange sum, and it may at first seem very difficult to approach. However, there is a very beautiful identity discovered by Leonhard Euler: where $i$ is the imaginary number $i=\sqrt{-1}$ (we will not prove this here, but perhaps in a later post). This means that the value of our sum is equal to the imaginary part of the complex number Let's simplify this... Lo and behold! Another geometric series. We can now apply our beloved formula for the sum of an infinite geometric series: or Now we can use Euler's formula: Now, to find the imaginary part, we need to get rid of the $i$ in the denominator: We can now extract the imaginary part: And so this is the answer that we are looking for, and Many other summation problems involving trigonometric functions can be solved using this identity.

And that concludes this post!